Travel Guide: Kazakhstan

Travel Guide: Kazakhstan

Table of Contents

- Brief History

- Geography

- Politics and Government

- Law and Criminal Justice

- Foreign Relations

- Administrative Divisions

- Economy & Commodities

- Science and Technology

- Philosophy

- Cultural Etiquette

- Sports and Recreation

- Environmental Concerns

- Marriage & Courtship

- Work Opportunities

- Education

- Communication & Connectivity

- National Symbols

- Tourism

- Visa and Entry Requirements

- Useful Resources

Brief History

The history of Kazakhstan is a vast and epic story, written across the immense expanse of the Eurasian steppe, a landscape that has shaped its people and its destiny. For millennia, this territory was the domain of nomadic horsemen. The first people known to inhabit the region were Scythian and Saka tribes, Iranian-speaking equestrians who roamed the grasslands from the 1st millennium BCE. Their legacy is found in the magnificent burial mounds, or kurgans, which contain elaborate golden artifacts, showcasing a sophisticated culture. This was the heartland of nomadic empires, a place of constant migration, conquest, and cultural exchange. The vast, open plains served as a natural highway, making Kazakhstan a crucial segment of the ancient Silk Road, the legendary network of trade routes that connected China with the Mediterranean. Cities like Taraz and Otrar flourished as vibrant centers of commerce, where goods, ideas, and religions from East and West converged.

The consolidation of a distinct Kazakh identity began in the 15th century with the formation of the Kazakh Khanate. This powerful nomadic state, founded by the sultans Janibek and Kerei, unified various Turkic and Mongol tribes, establishing a shared culture, language, and a territory that roughly corresponds to modern-day Kazakhstan. The Kazakhs were renowned for their nomadic pastoralism, raising vast herds of sheep, goats, and horses, and living in portable felt dwellings called yurts. This nomadic lifestyle fostered a deep connection to the land, a rich oral tradition of epic poetry, and a strong sense of clan identity. However, the Khanate faced constant external pressures, caught between the rising power of the Dzungars to the east and the expanding Russian Empire to the north. These challenges eventually led the Kazakh khans to seek Russian protection in the 18th century.

This request for protection gradually evolved into outright annexation, and by the mid-19th century, all of Kazakhstan was incorporated into the Russian Empire. The Tsarist period brought significant changes, including the settlement of Russian and Ukrainian peasants, which disrupted traditional nomadic patterns. The most profound and traumatic transformation came during the Soviet era. Under Stalin, the forced collectivization of agriculture in the 1930s resulted in a devastating famine that killed over a million Kazakhs and shattered the nomadic way of life. Later, Kazakhstan became a destination for internal exiles and the site of the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site and the Baikonur Cosmodrome. With the dissolution of the USSR, Kazakhstan declared its independence on December 16, 1991. Under the leadership of its first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, the country has since focused on leveraging its immense energy resources to build a modern nation, navigating a complex path of economic development and nation-building on the world stage.

Geography

The geography of Kazakhstan is defined by its immense scale and its dramatic, often stark, beauty. As the ninth-largest country in the world and the largest landlocked nation, its territory spans over 2.7 million square kilometers, stretching from the Caspian Sea in the west to the Altai Mountains on its eastern border with China and Russia. The dominant feature of the Kazakh landscape is the great Eurasian Steppe, an endless sea of grass and semi-desert that covers roughly a third of the country. This vast, flat expanse, punctuated by salt lakes and rolling hills, is the historical heartland of the nomadic peoples who once roamed its plains. The climate of the steppe is one of extreme continentality, with scorching hot summers and bitterly cold, windy winters, a harsh environment that has bred a resilient and hardy culture.

While the steppe dominates the popular imagination, Kazakhstan’s topography is remarkably varied. To the west, the country has a long coastline on the Caspian Sea, the world’s largest inland body of water, which holds vast reserves of oil and natural gas. North of the Caspian lies the Caspian Depression, a low-lying area that includes parts below sea level. In the far east and southeast, the flat plains give way to spectacular mountain ranges. The Tian Shan, or “Celestial Mountains,” form a majestic natural border with Kyrgyzstan and China, with towering, snow-capped peaks like Khan Tengri reaching over 7,000 meters. This region is a world away from the steppe, offering alpine meadows, dense forests of Tien-Shan spruce, and stunning glacial lakes like the famous Kaindy and Kolsai Lakes. This mountainous zone is a critical center of biodiversity and a growing hub for trekking, skiing, and ecotourism.

Water resources are unevenly distributed across this vast land. Major rivers like the Irtysh, Ishim, and Ural flow north towards Russia, while the Syr Darya flows westward into the desiccated Aral Sea, the site of one of the world’s most severe man-made environmental disasters. The country is dotted with thousands of lakes, the largest of which is Lake Balkhash in the southeast, a unique body of water that is fresh at its western end and saline at its eastern end. From the sun-baked deserts of the Mangystau Peninsula with its bizarre rock formations to the otherworldly landscapes of the Charyn Canyon, often compared to the Grand Canyon, and the vast, empty plains of the central highlands, the geography of Kazakhstan offers a breathtaking canvas of natural wonders, a land of epic scale and surprising diversity.

Politics and Government

The political system of the Republic of Kazakhstan is defined as a unitary republic with a strong presidential system of government. Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the country’s political landscape has been dominated by a powerful executive branch. The head of state is the President, who is elected by popular vote and holds significant authority. The President serves as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, sets the main direction of domestic and foreign policy, and has the power to appoint and dismiss the Prime Minister, cabinet ministers, and other key government officials. For nearly three decades, from independence until 2019, the country was led by its first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who shaped the nation’s post-Soviet political and economic trajectory. Even after his resignation, he retained considerable influence as the “Leader of the Nation” (Elbasy) and Chairman of the Security Council for a period.

The legislative branch of the government is a bicameral Parliament, which consists of two houses: the lower house, known as the Mazhilis, and the upper house, the Senate. The Mazhilis is the primary legislative body, composed of deputies who are elected through a mixed system of proportional representation from party lists and single-mandate districts. The Senate consists of deputies who are indirectly elected by regional legislative bodies (maslikhats), with a number of senators also being directly appointed by the President. While the Parliament is responsible for passing legislation, its powers are limited relative to the authority of the President. The dominant political force in the country has historically been the ruling party, currently known as Amanat (formerly Nur Otan), which has consistently held a large majority in the Parliament.

In recent years, under the leadership of President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Kazakhstan has embarked on a course of political reform aimed at decentralization and increasing political competition. These reforms have included constitutional amendments that have reduced some of the powers of the presidency, simplified the process for registering new political parties, and changed the electoral model for the Mazhilis to allow for more independent candidates. The government has framed these changes as a move towards a “New Kazakhstan” or a “Second Republic,” with a greater emphasis on political pluralism and public accountability. However, the political system remains highly centralized, and the process of democratic development is ongoing. The government’s primary focus continues to be on maintaining political stability, fostering economic growth, and balancing its relationships with its powerful neighbors, Russia and China.

Law and Criminal Justice

The legal system of the Republic of Kazakhstan is based on the civil law tradition, a model that traces its roots to Roman law and was heavily influenced by the legal framework of the Soviet Union. This system is distinct from the common law systems found in countries like the UK and the US. In Kazakhstan’s civil law system, the primary source of law is codified statutes and legislation passed by the Parliament. Judicial precedent, or decisions made in previous cases, is not legally binding, although it can be influential in guiding judicial interpretation. The Constitution of Kazakhstan, adopted in 1995, serves as the supreme law of the land, establishing the fundamental principles of the state, the rights and freedoms of citizens, and the structure of the government. The legal framework is extensive, with comprehensive codes governing civil, criminal, administrative, and procedural matters.

The criminal justice system is structured to handle the investigation, prosecution, and adjudication of criminal offenses. Law enforcement is primarily the responsibility of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which oversees the national police force. The investigation of crimes is conducted by police investigators and other specialized agencies. Once an investigation is complete, the case is handed over to the Public Prosecutor’s Office. This office, headed by the Prosecutor General, plays a powerful role in the system. Prosecutors are responsible for overseeing the legality of the investigation, approving indictments, and representing the state in court during a criminal trial. The system is inquisitorial in nature, meaning the judge takes an active role in examining the evidence and questioning witnesses, as opposed to the more adversarial system where the judge acts primarily as a neutral referee between the prosecution and the defense.

The judiciary in Kazakhstan is a hierarchical system. Cases are first heard in local district courts. Decisions from these courts can be appealed to regional courts, and the ultimate court of appeal is the Supreme Court of the Republic. In recent years, Kazakhstan has undertaken significant reforms aimed at modernizing its law and criminal justice system. These reforms have included efforts to increase judicial independence, improve the rights of the accused, introduce trial by jury for certain serious crimes, and enhance the transparency and efficiency of the courts. The government has also focused on liberalizing parts of the criminal code and promoting alternatives to incarceration for less serious offenses. These efforts are part of a broader strategy to align the country’s legal framework more closely with international standards and to build greater public trust in the justice system.

Foreign Relations

Kazakhstan’s foreign policy is a masterful balancing act, defined by its strategic location, its resource wealth, and its commitment to a “multi-vector” approach. Situated at the heart of Eurasia, landlocked between the two great powers of Russia and China, Kazakhstan’s primary diplomatic objective since its independence in 1991 has been to maintain friendly, stable, and pragmatic relations with all major global and regional players without becoming overly dependent on any single one. This multi-vector policy, first articulated by former President Nursultan Nazarbayev, has allowed the country to safeguard its sovereignty and pursue its national interests by fostering partnerships in all directions—north, east, south, and west.

The relationship with Russia to the north is arguably the most crucial. The two countries share the world’s longest continuous land border, deep historical and cultural ties from the Tsarist and Soviet eras, and a significant ethnic Russian population within Kazakhstan. They are close partners through organizations like the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). At the same time, Kazakhstan has cultivated an equally vital strategic partnership with China to its east. China is a massive consumer of Kazakhstan’s energy exports and a key investor in its infrastructure through the Belt and Road Initiative, which physically passes through Kazakhstan. Balancing the interests of these two powerful neighbors, while asserting its own sovereignty, is the central and most delicate task of Kazakh diplomacy.

Beyond its immediate neighborhood, Kazakhstan has actively pursued strong relationships with the United States and the European Union. These partnerships are crucial for attracting Western investment, particularly in the vital oil and gas sector, and for accessing advanced technology and expertise. Kazakhstan has positioned itself as a reliable partner in global security, most notably by voluntarily renouncing the nuclear arsenal it inherited from the USSR and becoming a world leader in the cause of nuclear non-proliferation. The country is also an active member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). By acting as a bridge between East and West and promoting dialogue and economic integration, Kazakhstan has successfully carved out a role for itself as a stable, sovereign, and influential nation in the heart of Asia.

Administrative Divisions

The administrative structure of the Republic of Kazakhstan is organized in a clear, hierarchical manner, reflecting its status as a unitary state where the central government holds significant authority. The primary level of administrative division consists of 17 regions, which are known in the Kazakh language as “oblystar.” In 2022, a major administrative reform led to the creation of three new regions, increasing the total from 14 to 17, in a move designed to improve public administration and promote more balanced regional development. These regions vary enormously in size and population, from the vast, sparsely populated regions of the western steppe to the more densely populated agricultural and industrial regions in the south and north.

In addition to the 17 regions, there are three cities that hold a special “city of republican significance” status. These are Astana, the nation’s futuristic capital; Almaty, the former capital and still the country’s largest city and cultural and financial hub; and Shymkent, a major urban center in the south. These three cities are administratively separate from the regions that surround them and report directly to the central government. Each of the 17 regions and the three cities of republican significance is headed by an “Akim,” or governor. The Akims of the regions and the three main cities are directly appointed by the President of the Republic, which ensures a strong vertical chain of command from the national government down to the local level.

Below the regional level, the administrative hierarchy is further subdivided. The regions are divided into districts, or “audandar,” which are also managed by appointed Akims. At the most local level, the structure includes rural districts and individual towns and villages. In recent years, as part of a broader political reform agenda, Kazakhstan has introduced direct elections for the Akims of some smaller towns and rural districts. This is a significant step towards decentralization and is intended to increase the accountability of local officials and give citizens a greater voice in their local governance. This multi-tiered system, from the 17 regions and 3 major cities down to the local districts, provides the framework through which the government administers public services, manages economic development, and maintains law and order across the vast territory of the country.

Economy & Commodities

The economy of Kazakhstan is the largest and most robust in Central Asia, a status built overwhelmingly on its immense wealth of natural resources. Since gaining independence in 1991, the country has leveraged its vast reserves of oil, gas, and minerals to fuel rapid economic growth and modernize its infrastructure. The energy sector is the undisputed backbone of the economy, with oil and natural gas accounting for the majority of the country’s export revenues and a significant portion of its GDP. Major oil fields, such as Kashagan, Tengiz, and Karachaganak, located in the western part of the country near the Caspian Sea, have attracted billions of dollars in foreign investment from global energy giants. This has transformed Kazakhstan into a major player in the global energy market, with a network of pipelines transporting its oil and gas to China, Russia, and Europe.

Beyond hydrocarbons, Kazakhstan is a treasure trove of mineral commodities. It is the world’s largest producer of uranium, a critical component for the nuclear power industry. The country also possesses enormous deposits of other valuable minerals, including chrome, copper, zinc, lead, manganese, and gold. This mineral wealth has fostered a large and important mining and metallurgy sector, which is another key driver of industrial output and exports. The vast agricultural lands of the northern steppe make Kazakhstan a major grain producer, particularly of wheat, which is a significant export commodity. However, this heavy reliance on the extraction and export of raw materials makes the Kazakh economy highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global commodity prices. When oil and metal prices are high, the economy booms, but when they fall, the country faces significant economic pressure.

Recognizing the risks of this dependency, the government of Kazakhstan has embarked on a long-term strategy of economic diversification. The goal is to develop other sectors of the economy to create a more resilient and sustainable growth model. Key areas of focus include developing the manufacturing sector, expanding transportation and logistics (leveraging the country’s position as a transit hub between Asia and Europe), and fostering a digital and knowledge-based economy. The government has implemented various programs to attract investment into non-extractive industries, support small and medium-sized enterprises, and improve the overall business climate. The development of the Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC), which operates on principles of English common law, is a flagship project aimed at positioning the country as a leading financial hub for the region. The success of this diversification effort will be crucial for Kazakhstan’s long-term economic prosperity.

Science and Technology

Since its independence, Kazakhstan has placed a strategic emphasis on the development of science and technology as a cornerstone for diversifying its resource-based economy and building a modern, knowledge-driven society. Acknowledging the need to move beyond its reliance on oil and minerals, the government has launched numerous state programs aimed at fostering innovation, supporting research and development (R&D), and integrating new technologies across various sectors. The country’s scientific heritage is rooted in the Soviet era, which established a strong foundation in fundamental sciences like physics, mathematics, and geology. A key legacy of this period is the Baikonur Cosmodrome, the world’s first and largest operational space launch facility, which is leased by Russia from Kazakhstan. This iconic site continues to serve as a powerful symbol of scientific achievement and inspires national interest in space science and satellite technology.

The contemporary focus of Kazakhstan’s science and technology policy is on creating a robust innovation ecosystem. A central element of this is the development of technology parks and innovation clusters, such as the Astana Hub, which aims to become a leading international technopark for IT startups. These hubs provide infrastructure, mentorship, and access to venture capital to help nurture new tech companies. The government is also actively promoting the digitalization of the economy and public services, a strategy known as “Digital Kazakhstan.” This initiative has led to significant progress in areas like e-governance, fintech, and the digital transformation of traditional industries like mining and agriculture. The goal is to enhance efficiency, transparency, and competitiveness through the widespread adoption of digital technologies.

Higher education institutions are critical to this national vision. Universities like Nazarbayev University, which partners with leading international universities and emphasizes research and English-language instruction, are designed to cultivate a new generation of scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs. The government also provides grants and funding for scientific research in priority areas, including renewable energy, biotechnology, information and communication technologies, and materials science. Despite this progress, challenges remain. The country is working to increase its overall expenditure on R&D, strengthen the links between academic research and private industry, and improve the commercialization of scientific discoveries. Building a critical mass of world-class researchers and fostering a culture of private-sector innovation are key priorities as Kazakhstan strives to secure its place as a technologically advanced nation.

Philosophy

The philosophical tradition of Kazakhstan is a rich and layered tapestry, woven from the threads of ancient nomadic wisdom, Islamic Sufism, and more recent Russian and Western intellectual currents. At its very core lies the nomadic worldview of the Kazakh people, shaped by the vast and unforgiving expanse of the steppe. This philosophy, known as “Tengrism” in its ancient form, was a pantheistic belief system centered on the worship of the eternal blue sky, “Tengri,” as the supreme deity. It fostered a deep, reverent connection to nature, where mountains, rivers, and trees were imbued with spiritual significance. This worldview emphasized harmony between humanity and the natural world, a cyclical understanding of time, and a profound respect for one’s ancestors. Key values derived from this nomadic heritage include hospitality, resilience, freedom of spirit, and the importance of the clan and community over the individual.

With the arrival of the Silk Road, new philosophical and religious ideas permeated the region. Islam, particularly its mystical Sufi branch, found fertile ground among the nomadic Kazakhs. Thinkers and poets like Khoja Ahmed Yasawi, a 12th-century Sufi master from what is now southern Kazakhstan, were instrumental in blending Islamic teachings with pre-existing Turkic cultural and spiritual beliefs. This syncretic form of Islam was less about rigid dogma and more about inner spirituality, tolerance, and the direct personal experience of God. Yasawi’s “Divan-i Hikmet” (Book of Wisdom) conveyed these ideas in a simple, poetic Turkic language that resonated with the common people, shaping a uniquely Central Asian Islamic philosophy that valued wisdom, compassion, and moral integrity.

The Russian and Soviet periods introduced a powerful new wave of Western philosophical thought, including the Enlightenment, humanism, and, most forcefully, Marxism-Leninism. This era saw the rise of a modern Kazakh intelligentsia who sought to synthesize their national heritage with modern ideas. Figures like Abai Kunanbaiuly, a 19th-century poet and philosopher, are revered as the father of modern Kazakh literature and thought. Abai critically examined Kazakh society, urging his people to embrace education, science, and a more settled, enlightened way of life, while still cherishing the best of their nomadic traditions. In the post-independence era, Kazakhstan is engaged in a continuous philosophical dialogue, seeking to define its modern identity by re-examining its nomadic and Sufi roots, grappling with the legacy of the Soviet experience, and integrating the values of a globalized, modern world. This search for a “Kazakh way” is a quest to build a national philosophy based on tolerance, pragmatism, and a unique synthesis of East and West.

Cultural Etiquette

Understanding and respecting cultural etiquette is key to any successful interaction in Kazakhstan, a country where traditions of hospitality and respect are deeply ingrained. The cornerstone of Kazakh culture is an immense respect for elders. In any social or professional setting, elders are greeted first, served first, and given the best seat. When speaking to an elder, it is important to use a respectful tone and formal language. Younger people are expected to listen attentively and not to interrupt. This reverence for age is a fundamental pillar of the society, and showing proper deference will be greatly appreciated. Hospitality is another sacred value. Guests are considered a blessing from God, and hosts will go to extraordinary lengths to make a visitor feel welcome, often presenting them with a lavish spread of food and drink, even on a casual visit.

When invited to a Kazakh home, it is a great honor. You should accept the invitation enthusiastically. It is customary to bring a small gift for the hosts, such as pastries, chocolates, or flowers (always in odd numbers). Upon entering a home, you should remove your shoes. The host will likely offer you the seat of honor (“tor”), which is typically the seat furthest from the door. During a meal, you will be offered food and drink multiple times. It is polite to accept, as refusing can be seen as a rejection of the host’s generosity. The national drink is “kumis” (fermented mare’s milk), and while you are not obligated to drink it, trying a small amount is a sign of respect. The most important guest is often offered a special piece of the main dish, such as the head of the sheep in a traditional feast, which is a great sign of honor.

In general interactions, greetings are warm. A handshake is common between men, often using both hands to show extra respect. It is less common for a man to initiate a handshake with a woman, and it is best to wait for her to extend her hand first. Direct eye contact is a sign of sincerity and honesty. The concept of saving face is important, so it is best to avoid public criticism or confrontation. Kazakhs are proud of their history and culture, and showing genuine interest by asking questions about their traditions, family, and country will be very well received. While the cities may have a modern, international feel, these underlying customs of respect, generosity, and community are the true heart of Kazakh culture, and observing them will lead to warm and memorable experiences.

Sports and Recreation

Sports and recreation in Kazakhstan are a vibrant reflection of the nation’s dual heritage, blending traditional nomadic games with popular modern Olympic sports. The country’s nomadic past has bequeathed a rich legacy of equestrian sports that are a central part of cultural festivals and national celebrations. The most thrilling of these is “kokpar,” a wild and dramatic game that is the Central Asian equivalent of polo. Instead of a ball, two teams of skilled horsemen compete to drag a headless goat carcass into a goal. It is a fierce and physically demanding sport that showcases incredible horsemanship and strength. Another popular traditional sport is “kyz kuu,” or “girl chasing,” a playful race where a young man on horseback pursues a young woman. If he catches her, he earns a kiss, but if he fails, she turns and chases him back, armed with a whip.

Alongside these traditional pastimes, Kazakhstan has enthusiastically embraced modern sports and has achieved significant success on the international stage. Boxing is a source of immense national pride, and the country has consistently produced Olympic and world champions, known for their technical skill and toughness. Weightlifting and wrestling are also national strong suits, reflecting a cultural emphasis on strength and martial prowess. In winter sports, speed skating and biathlon are popular, with Kazakh athletes performing well in international competitions. Football (soccer) is the most popular team sport, with a domestic league and a passionate following for the national team’s fortunes in UEFA competitions. Ice hockey is also extremely popular, with the team Barys Nur-Sultan (now Barys Astana) competing in the professional Kontinental Hockey League (KHL).

The vast and diverse landscapes of Kazakhstan provide a spectacular natural playground for outdoor recreation. The majestic Tian Shan and Altai mountains in the southeast and east are a paradise for trekking, mountaineering, and rock climbing, offering pristine wilderness and breathtaking scenery. The Medeu high-mountain ice skating rink, located just outside Almaty, is a world-famous facility, and the nearby Shymbulak ski resort is the most advanced in Central Asia, offering excellent slopes for skiing and snowboarding. The numerous lakes and rivers provide opportunities for fishing, boating, and kayaking. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in ecotourism and birdwatching, particularly in the country’s extensive network of national parks and nature reserves, where one can see unique wildlife like the snow leopard, argali sheep, and vast flocks of migratory birds.

Environmental Concerns

Kazakhstan, a country of immense size and resource wealth, faces a legacy of severe environmental challenges, many of which are a direct result of Soviet-era industrial and military policies. The most infamous and devastating of these is the desiccation of the Aral Sea. Once the fourth-largest lake in the world, the Aral Sea, which is shared with Uzbekistan, began to shrink dramatically in the 1960s after the Soviet government diverted the two main rivers that fed it, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, to irrigate vast cotton fields. This has resulted in a catastrophic environmental disaster. The sea has shrunk to a fraction of its former size, leaving behind a vast, salt-covered desert called the Aralkum. This has destroyed the once-thriving fishing industry, devastated the local economy, and created severe public health problems as toxic, salty dust from the exposed seabed is blown by the wind across the region.

Another profound environmental scar was left by the Soviet nuclear testing program. The Semipalatinsk Test Site, also known as “The Polygon,” in the northeast of the country, was the primary testing venue for the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons. Between 1949 and 1989, hundreds of nuclear devices were detonated here, both above and below ground, releasing massive amounts of radioactive fallout into the atmosphere and contaminating a vast area of land. This has had long-lasting and tragic consequences for the health of the local population, with significantly elevated rates of cancer, birth defects, and other radiation-related illnesses. Since independence, Kazakhstan has become a world leader in the anti-nuclear movement, shutting down the test site and playing a key role in promoting global nuclear disarmament, but the environmental cleanup and long-term health monitoring remain immense challenges.

Beyond these historical disasters, modern Kazakhstan faces ongoing environmental pressures. The country’s heavy reliance on the oil, gas, and mining industries creates risks of air and water pollution, soil contamination, and habitat destruction if not managed properly. The vast industrial cities of the Soviet era often suffer from poor air quality. The Caspian Sea ecosystem is under threat from pollution related to offshore oil extraction. Furthermore, desertification is a growing concern, driven by overgrazing and poor land management practices in the country’s vast steppe and semi-desert regions. In response, the government of Kazakhstan has been placing an increasing emphasis on environmental protection and “green” development, investing in renewable energy, water conservation, and reforestation projects to mitigate these challenges and build a more sustainable future.

Marriage & Courtship

In Kazakhstan, marriage and courtship are a fascinating blend of deeply rooted traditions and modern sensibilities. While urban youth in cities like Almaty and Astana may have a dating culture similar to that in Western countries, meeting in cafes or through apps, traditional values, particularly the importance of family and respect for elders, remain paramount across the society. The family’s approval is a crucial element in the journey toward marriage. It is not just a union of two individuals but an alliance between two families. Therefore, a formal introduction of the potential spouse to one’s parents is a significant milestone. The parents’ blessing (“bata”) is highly sought after and is considered essential for a happy and prosperous marriage.

Several traditional rituals are still widely practiced. One of the key pre-wedding events is the “kuda tusu,” a formal meeting between the families where the groom’s family visits the bride’s family to ask for her hand in marriage and to negotiate the “kalym” (bride price). While the kalym was historically a payment in livestock, today it is more often a symbolic gift of money or valuable items, intended to demonstrate the groom’s ability to provide for his new family and to honor the bride’s parents. The wedding celebration itself is a grand and lavish affair, often involving hundreds of guests. It is a vibrant display of Kazakh hospitality, featuring enormous feasts, traditional music and dancing, and numerous toasts and speeches. The bride often wears a modern white dress for part of the celebration, but will also don a traditional, ornate Kazakh wedding dress with a tall, conical headdress called a “saukele.”

Work Opportunities

The landscape of work opportunities in Kazakhstan is largely defined by its resource-rich economy, with the oil and gas sector serving as the primary engine of employment for skilled professionals and expatriates. The western regions of the country, particularly around the cities of Atyrau and Aktau near the Caspian Sea, are the epicenters of this industry. Major multinational energy corporations, in partnership with the state-owned company KazMunayGas, operate massive extraction and processing projects. This creates a high demand for a wide range of professionals, including petroleum engineers, geologists, project managers, logistics specialists, and health and safety experts. These positions, especially those for expatriates, are often highly lucrative, with competitive salaries and benefits packages designed to attract top global talent to a challenging and remote work environment.

Beyond oil and gas, the extensive mining and metallurgy sector is another major employer. As a world leader in uranium and chrome production, and a significant producer of copper and zinc, Kazakhstan’s industrial cities in the central and eastern parts of the country offer opportunities for mining engineers, metallurgists, and other technical specialists. In recent years, as part of its economic diversification strategy, the government has been actively promoting other sectors. The construction industry has boomed, particularly in the capital, Astana, with its futuristic architecture, creating jobs for architects, civil engineers, and construction workers. The transportation and logistics sector is also growing, as Kazakhstan seeks to leverage its strategic position as a land bridge between China and Europe within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative.

For those seeking work outside of heavy industry, opportunities are emerging, though they are more concentrated in the major urban centers of Almaty and Astana. The financial sector is developing, with the Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) aiming to become a regional hub, creating a need for professionals in banking, finance, and law. There is also a growing IT sector, supported by government initiatives like the Astana Hub for startups. For foreign nationals, proficiency in English is a major asset, especially in international companies. However, knowledge of Russian, which is widely spoken in business, or Kazakh, the state language, is a significant advantage. Obtaining a work permit for expatriates typically requires a firm job offer from a sponsoring company, which must justify the need to hire a foreign specialist over a local candidate.

Education

The education system in Kazakhstan is a state-priority, viewed as fundamental to the nation’s goal of becoming one of the world’s most developed countries. Inheriting a strong and centralized structure from the Soviet era, the system has undergone significant reforms since independence to modernize its curriculum, align with international standards, and meet the demands of a market economy. Education is compulsory and free for all citizens through the secondary level. The system begins with one year of pre-school, followed by four years of primary school, five years of lower secondary school, and two years of upper secondary school, for a total of 12 years of schooling. The government has also implemented a trilingual education policy, with the goal of producing graduates fluent in Kazakh (the state language), Russian (the official language of interethnic communication), and English (the language of international business and technology).

Upon completion of secondary school, students who wish to pursue higher education must take the Unified National Testing (UNT), a standardized examination that serves as both a final school exam and a university entrance test. A student’s score on the UNT is a key determinant for admission to universities and for receiving state-funded educational grants. The country has a wide network of universities, academies, and institutes, both public and private. A flagship initiative in higher education has been the establishment of Nazarbayev University in Astana. Modeled on Western research universities, it partners with leading global institutions, offers instruction entirely in English, and focuses heavily on research and innovation, aiming to cultivate a new generation of leaders and scientists for the country.

Another cornerstone of Kazakhstan’s educational strategy is the Bolashak (Future) international scholarship program. Established in 1993, this highly prestigious program is funded by the state and sends thousands of the country’s most talented students abroad to pursue undergraduate and postgraduate degrees at top universities around the world. The condition of the scholarship is that recipients must return to Kazakhstan to work for at least five years, thereby contributing their acquired knowledge and skills to the country’s development. This massive investment in human capital has been instrumental in building a highly educated, globally-minded professional class. While the system faces ongoing challenges, such as bridging the quality gap between urban and rural schools and improving teacher training, Kazakhstan’s commitment to education remains a central pillar of its long-term national vision.

Communication & Connectivity

Kazakhstan has made enormous strides in developing its communication and connectivity infrastructure, a remarkable achievement given its vast territory and low population density. In the digital realm, the country has a surprisingly high rate of internet penetration, with a competitive mobile communications market driving progress. Several mobile operators, including Kcell, Beeline, and Tele2, provide extensive 4G/LTE coverage to most populated areas, including all major cities and many rural towns. This has made mobile internet the primary means of online access for the majority of the population. The government’s “Digital Kazakhstan” program has been a key driver, aiming to expand broadband access, develop e-governance services, and foster a local IT industry. As a result, many government services, banking, and commerce are now readily available online, significantly improving efficiency for citizens and businesses.

While mobile connectivity is strong, fixed-line broadband infrastructure is also expanding. Major cities like Astana and Almaty have widespread access to high-speed fibre-optic internet, offering affordable and reliable connections for homes and businesses. In terms of language, communication is typically seamless for a wide range of visitors. Kazakh is the state language, and its use is being increasingly promoted by the government. However, Russian remains the official language of interethnic communication and is spoken fluently by almost the entire population, serving as the lingua franca of business, government, and daily life in the cities. English proficiency is growing, especially among the youth, in the business community, and in the tourism sector in major cities, but it is not as widely spoken in rural areas.

Physical connectivity across this immense country is a major logistical undertaking. Air travel is the most efficient way to cover the vast distances between major cities. The national carrier, Air Astana, has a modern fleet and a strong international reputation, connecting the main hubs of Astana, Almaty, and Atyrau with a network of domestic and international flights. The railway system, a legacy of the Soviet era, is another vital mode of transport. An extensive network of trains connects all major population centers, offering an affordable, albeit slow, way to travel and see the vast steppe landscape. In recent years, the country has invested in modern, high-speed Talgo trains on key routes, such as between Almaty and Astana, which have significantly reduced travel times. A growing network of modern highways is also improving road travel between cities.

National Symbols

The national symbols of Kazakhstan are a rich and evocative expression of the country’s identity, drawing heavily on its nomadic heritage, its natural landscapes, and its aspirations for a bright future. The national flag, adopted in 1992, is a powerful and elegant design. It features a sky-blue background, which symbolizes peace, unity, and the endless sky of the steppe under which the Kazakh people have lived for centuries. In the center of the flag is a golden sun with 32 rays, representing life, energy, and wealth. Beneath the sun soars a golden steppe eagle, a bird that has been a symbol of power, freedom, and independence for the nomadic tribes of the region for generations. On the hoist side of the flag, there is a vertical ornamental band of “koshkar-muiz” (the ram’s horn), a traditional Kazakh pattern that represents the art and cultural traditions of the people.

The national emblem of Kazakhstan is a circular design that is rich with symbolism. The central element is the “shanyrak,” the circular, domed top of a traditional Kazakh yurt. The shanyrak symbolizes the family home, peace, and the unity of all peoples living in Kazakhstan as part of a common home. The shanyrak is depicted against a blue background, representing the sky, with sunbeams radiating outwards. Flanking the shanyrak are two mythical, winged horses called “tulpars.” In Kazakh folklore, the tulpar represents courage and the dream of a strong, prosperous nation. At the top of the emblem is a five-pointed star, symbolizing the high aspirations and ideals of the Kazakh people, while at the bottom, the word “QAZAQSTAN” is inscribed in the Latin alphabet, reflecting the country’s modernizing identity.

The national anthem, “Meniń Qazaqstanym” (My Kazakhstan), is a stirring and patriotic song. Originally a popular song from the Soviet era, it was adapted with new lyrics and officially adopted as the national anthem in 2006. The lyrics speak of the country’s ancient glory, its vast open spaces, and the bravery and unity of its people. Beyond these official symbols, certain flora and fauna are deeply connected to the national identity. The golden eagle is revered, and the snow leopard, a rare and elusive inhabitant of the Tian Shan mountains, is another powerful symbol of the nation’s wild natural heritage. The tulip, which is believed to have originated in the steppes of Central Asia, is also a cherished floral symbol, representing the beauty and renewal of the spring landscape.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| National Flag | A sky-blue field with a golden sun, a soaring steppe eagle, and a national ornamental pattern. |

| National Emblem | A circular emblem featuring a shanyrak (yurt top), flanked by mythical winged horses (tulpars). |

| National Anthem | “Meniń Qazaqstanym” (My Kazakhstan), a song celebrating the nation’s land, history, and people. |

| Symbolic Animal | Golden Eagle (Berkut), symbolizing freedom and power; also the Snow Leopard. |

| Symbolic Plant | Tulip (Qyzǵaldaq), a flower native to the region, symbolizing spring and beauty. |

| Cultural Symbol | The Shanyrak, the top of a yurt, representing home, family, and the universe. |

Tourism

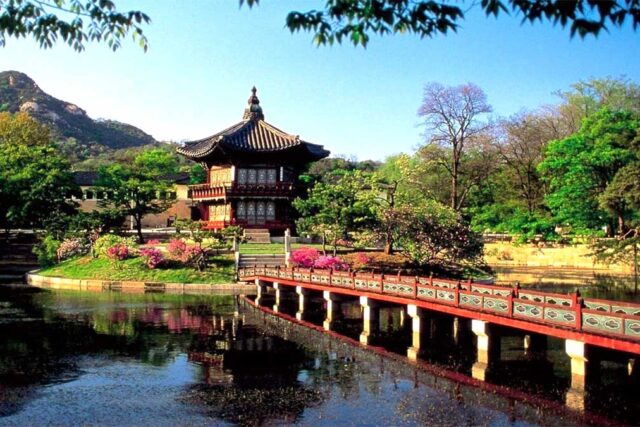

Kazakhstan, a land of epic proportions and nomadic soul, is emerging as one of the world’s most intriguing and off-the-beaten-path travel destinations. For adventurers and nature lovers, the country is a paradise of unparalleled scale and diversity. The main tourist gateway is often the southern city of Almaty, beautifully situated at the foot of the majestic Tian Shan mountains. From here, visitors can easily access a world of outdoor adventure. Just a short drive from the city leads to the Shymbulak ski resort, the high-altitude Medeu ice rink, and the breathtaking Big Almaty Lake. Further afield, the Almaty region offers some of the country’s most spectacular natural wonders, including the otherworldly landscapes of the Charyn Canyon, often called the Grand Canyon’s little brother; the stunning, turquoise Kolsai Lakes; and the submerged forest of Lake Kaindy, where birch trees rise eerily from the water.

In stark contrast to the natural beauty of the south is the futuristic and ambitious capital city, Astana (formerly Nur-Sultan). Built on the northern steppe, Astana is a showcase of 21st-century architecture, with a skyline dominated by fantastical structures designed by world-renowned architects. Key sights include the Bayterek Tower, a monument symbolizing a Kazakh folk tale, from which visitors can get a panoramic view of the city; the Khan Shatyr, a giant, translucent tent-like structure that houses a shopping and entertainment complex complete with an indoor beach; and the Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, a giant glass pyramid. A trip to Kazakhstan also offers a chance to delve into unique aspects of history, from exploring the ancient Silk Road city of Turkistan, with its magnificent mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi, to visiting the Baikonur Cosmodrome, the launchpad for Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin, where it is still possible to witness rocket launches.

Visa and Entry Requirements

Kazakhstan has significantly liberalized its visa policy in recent years, making it easier than ever for many nationalities to visit for tourism and business. A key development is the unilateral visa-free regime that the country has established for citizens of numerous countries. This list includes all member states of the European Union, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, and many others. Citizens of these countries can enter Kazakhstan without a visa for stays of up to 30 calendar days. This visa-free access has been a game-changer for the tourism industry, allowing for convenient and spontaneous short-term travel. It is important to note that if a traveler under this regime exits and re-enters, the total period of stay cannot exceed 90 days within any 180-day period.

For all travelers, a passport that is valid for at least six months beyond the planned date of departure from Kazakhstan is required. It is also essential that the passport has at least one blank page for entry and exit stamps. Upon arrival at an international airport or land border, visitors will need to fill out a migration card, which is often provided on the plane or at the immigration counter. This card is stamped by the border official and must be kept with your passport for the duration of your stay. It is very important not to lose this card, as it must be presented upon departure. Previously, foreign visitors were required to register with the local migration police within a few days of arrival, but this requirement has been abolished for tourists staying less than 30 days, greatly simplifying the travel process.

For citizens of countries not covered by the visa-free regime, or for those wishing to stay longer than 30 days or for purposes other than tourism (such as work or study), a visa must be obtained in advance from a Kazakhstani embassy or consulate. The process typically requires a letter of invitation from a sponsoring entity in Kazakhstan, although this requirement has also been relaxed for many nationalities applying for a tourist visa. The government has also introduced an e-visa system for citizens of many countries, allowing them to apply online for a single-entry tourist visa, provided they have a letter of invitation. As visa policies can and do change, it is absolutely essential for all travelers to verify the most current requirements for their specific nationality with the official website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan or the nearest embassy before making any travel plans.

Useful Resources

- Kazakhstan Travel – Official Tourism Website – The national tourism portal with information on destinations, activities, and travel planning.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan – Official source for visa policies, consular information, and foreign relations.

- Air Astana – The official website of Kazakhstan’s national airline, for booking domestic and international flights.

- Kazakhstan Temir Zholy (Railways) – Official portal for booking train tickets within Kazakhstan.

- The Astana Times – A leading English-language news source for current events and developments in Kazakhstan.