🇰🇮 Kiribati Travel Guide

Table of Contents

- 21. Brief History

- 22. Geography

- 23. Politics and Government

- 24. Law and Criminal Justice

- 25. Foreign Relations

- 26. Administrative Divisions

- 27. Economy & Commodities

- 28. Science and Technology

- 29. Philosophy

- 30. Cultural Etiquette

- 31. Sports and Recreation

- 32. Environmental Concerns

- 33. Marriage & Courtship

- 34. Work Opportunities

- 35. Education

- 36. Communication & Connectivity

- 37. National Symbols

- 38. Tourism

- 39. Visa and Entry Requirements

- 40. Useful Resources

21. Brief History

The history of Kiribati is a profound story of human resilience, masterful navigation, and cultural endurance in one of the most remote and challenging environments on Earth. The islands, now known as Kiribati, were first settled by Austronesian peoples who journeyed from Southeast Asia, arriving sometime between 3000 BC and 1300 AD. These first inhabitants, the ancestors of the modern I-Kiribati people, developed a sophisticated and self-sufficient culture perfectly adapted to life on low-lying coral atolls. They were expert navigators, using complex knowledge of stars, wave patterns, and bird migrations to travel between the scattered islands. Society was traditionally organized around the ‘kainga’ (extended family group) and governed by village elders known as ‘unimane’. Around the 14th century, the southern islands experienced an influx of people from Samoa and Tonga, which introduced new cultural elements and led to a period of adaptation and integration, shaping the homogenized Micronesian culture found today.

European contact began sporadically in the 16th century, but it was not until the early 19th century that whalers, traders, and missionaries started to arrive in significant numbers. The islands were charted and named the Gilbert Islands by British Royal Navy Captain Thomas Gilbert in 1788. The arrival of Europeans brought profound changes, introducing new technologies, diseases, and the Christian religion, which gradually blended with or replaced traditional beliefs. The latter half of the 19th century was a turbulent period marked by the recruitment, often forceful, of I-Kiribati men to work on plantations in places like Fiji and Australia, a practice known as “blackbirding.” To establish order and protect its interests, Great Britain declared the Gilbert Islands a British Protectorate in 1892, later combining them with the neighboring Ellice Islands (modern Tuvalu) to form the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony in 1916.

The 20th century brought further upheaval. The discovery of rich phosphate deposits on Banaba (Ocean Island) led to intensive mining that devastated the island’s environment and resulted in the forced relocation of the Banaban people to Rabi Island in Fiji. During World War II, the Gilbert Islands became a key battleground in the Pacific War. The brutal Battle of Tarawa in 1943 was one of the deadliest conflicts in U.S. Marine Corps history and left a lasting scar on the island. After the war, a move towards self-governance began. Ethnic and cultural differences led to the peaceful separation of the Polynesian Ellice Islands from the Micronesian Gilbert Islands in 1975, with the former becoming the independent nation of Tuvalu. On July 12, 1979, the Gilbert Islands, along with the Phoenix and Line Islands, achieved full independence from the United Kingdom, becoming the sovereign Republic of Kiribati. The new nation chose the name “Kiribati” (pronounced “Kiribas”), the local rendition of “Gilberts,” to honor its main island group while embracing its full geographical identity.

Back to Top22. Geography

The geography of Kiribati is unique and defines its very existence, making it one of the most geographically remarkable and vulnerable nations on Earth. The country consists of 33 coral islands and atolls, with all but one—the raised limestone island of Banaba—being low-lying coral atolls that barely rise more than a few meters above sea level. These islands are scattered across a vast expanse of the central Pacific Ocean, straddling the equator and, uniquely, extending into all four hemispheres. The total land area of Kiribati is a mere 811 square kilometers, yet its islands are dispersed over an immense 3.5 million square kilometers of ocean. This gives Kiribati the largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) to land area ratio in the world, meaning its identity and economy are inextricably linked to the surrounding marine environment. The sheer oceanic expanse makes transportation and communication between the island groups a significant logistical challenge.

The nation is composed of three main island groups, each with distinct geographical characteristics and histories. The Gilbert Islands are the westernmost group, comprising 16 atolls where the vast majority of the population, including the capital, South Tarawa, is located. The islands form a chain running from north to south. The second group is the Phoenix Islands, located to the east of the Gilberts. This group is almost entirely uninhabited and is home to the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA), one of the largest marine protected areas in the world. PIPA is a UNESCO World Heritage site, recognized for its pristine ecosystem, which includes numerous coral reefs, seamounts, and an abundance of marine life. The third and easternmost group is the Line Islands. This chain includes Kiritimati (Christmas Island), which is the largest coral atoll in the world by land area and accounts for over 70% of Kiribati’s total landmass.

A fascinating geographical feature of Kiribati is its relationship with the International Date Line. The country’s vast east-to-west spread once meant that the eastern and western parts of the nation were on different days. To unify the country, in 1995, Kiribati moved the International Date Line eastward to encompass all of its islands. This move placed the Line Islands in the world’s most advanced time zone (UTC+14), making Kiribati the first country to greet the new day and the new millennium. The low-lying nature of its atolls, which are essentially rings of coral and sand surrounding a central lagoon, makes the country extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion into freshwater supplies are existential threats that dominate Kiribati’s national and international agenda, making its geography a subject of global environmental concern.

Back to Top23. Politics and Government

The politics and government of Kiribati operate within the framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic, a system that blends elements of the British Westminster model with unique local traditions. The Constitution of Kiribati, adopted upon independence in 1979, establishes the nation as a sovereign republic and guarantees free and open elections. The national government is structured into three distinct branches—the executive, the legislative, and the judicial—to provide a system of checks and balances. Unlike many parliamentary systems where the head of government is chosen by the legislature, Kiribati has a unique presidential system. The President, known as the ‘Beretitenti’, is both the head of state and the head of government. The Beretitenti is directly elected by the citizens in a national vote, but the candidates for the presidency are first nominated from among the members of the newly elected parliament. This hybrid system ensures the president has a popular mandate while also being a member of the legislature.

The legislative branch of the government is the unicameral parliament, the ‘Maneaba ni Maungatabu’ (House of Assembly). It is composed of 46 members: 44 members are elected from 23 constituencies for four-year terms, one member is a nominated representative of the Banaban community living on Rabi Island in Fiji, and the Attorney General served as an ex-officio member until a constitutional change in 2016. The Maneaba is the supreme legislative body, responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, and holding the executive branch accountable. While formal political parties exist, such as the Tobwaan Kiribati Party and the Boutokaan Kiribati Moa Party, their structure and discipline are often informal. Political affiliations can be fluid, with ad hoc coalitions frequently forming around specific issues or personalities rather than rigid ideologies. This creates a dynamic and sometimes unpredictable political environment.

The executive branch is led by the Beretitenti, who is limited to serving a maximum of three four-year terms. The President appoints a Vice President (‘Kauoman ni Beretitenti’) and a cabinet of up to 13 ministers from among the elected members of the Maneaba ni Maungatabu. This cabinet is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the country and the implementation of government policies. The judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches, a principle enshrined in the constitution. The judicial system is headed by the High Court, which is based in the capital, South Tarawa, and a Court of Appeal. The President appoints the chief justices and other judges based on the advice of the cabinet and other commissions. This structure of governance, combining democratic elections with traditional consensus-building elements embodied in the concept of the ‘maneaba’ (meeting house), provides a framework for navigating the unique challenges facing this island nation.

Back to Top24. Law and Criminal Justice

The legal system of Kiribati is a distinctive pluralistic framework, drawing from several sources of law that reflect its unique history and cultural context. The supreme law of the land is the Constitution of Kiribati, adopted in 1979, which guarantees fundamental human rights and outlines the structure of the state. Below the constitution, the primary source of formal law is statutory law, which consists of ordinances enacted by the ‘Maneaba ni Maungatabu’ (the national parliament). As a former British colony, Kiribati’s legal system also incorporates the principles of English common law and equity, as well as certain statutes of the United Kingdom’s parliament that were applicable before independence. This inherited British framework provides the basis for much of the country’s civil and criminal procedure. The court system is structured hierarchically, with magistrates’ courts at the local level handling the majority of civil and criminal cases.

A crucial and deeply integrated part of the justice system is customary law. Traditional customs and practices, which governed I-Kiribati society for centuries before European contact, continue to hold significant authority, particularly in matters of land ownership, family disputes, and local community issues. The Constitution and the Laws of Kiribati Act explicitly recognize customary law as a source of law, provided it is not inconsistent with the Constitution or statutory law. Disputes over land, which is a critically scarce and valuable resource on the atolls, are often first heard in local Lands Courts, where knowledge of genealogy and custom is paramount. This recognition of customary law allows for a system of justice that is culturally relevant and accessible to the people, blending traditional conflict resolution methods with the formal state legal system. The role of ‘unimane’ (village elders) remains vital in mediating disputes and maintaining social harmony within communities.

The criminal justice system is administered by the Kiribati Police and Prison Service, which is responsible for law enforcement, maintaining public order, and managing correctional facilities. Crime rates in Kiribati are generally low compared to many other countries, with most offenses being related to petty theft and public drunkenness. However, the country does face challenges. The formal justice system can be slow and under-resourced, particularly in the remote outer islands. The High Court, located in the capital South Tarawa, serves as the superior court with jurisdiction over serious criminal and civil cases and also hears appeals from the magistrates’ courts. The ultimate appellate court is the Kiribati Court of Appeal. The criminal code prohibits certain acts, and it is important for visitors to be aware of local laws; for example, sexual acts between individuals of the same sex are illegal. The justice system as a whole represents a continuous effort to balance the demands of a modern state with the enduring strength of its cultural traditions.

Back to Top25. Foreign Relations

The foreign relations of Kiribati are fundamentally shaped by its unique circumstances as a small, remote island nation facing the existential threat of climate change. Its foreign policy is driven by a pragmatic need to secure development assistance, build climate resilience, and amplify its voice on the international stage. Kiribati maintains close and crucial relationships with its key development partners in the Pacific, most notably Australia and New Zealand. These two nations are the country’s largest aid donors, providing essential financial and technical support across all sectors, including education, healthcare, infrastructure, and maritime security. They are also important trade partners and play a significant role in regional cooperation through forums like the Pacific Islands Forum. Japan is another vital partner, particularly in the fisheries sector, providing aid and having agreements to fish within Kiribati’s vast exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Climate change is the central and overriding issue in Kiribati’s foreign policy. As one of the lowest-lying nations in the world, the country is on the front line of the climate crisis, facing the imminent threats of sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and saltwater contamination of its freshwater sources. Consequently, Kiribati has adopted a highly active and vocal role in international climate diplomacy. It is a prominent member of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), a coalition of island nations that advocate for stronger global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and provide climate finance for adaptation. Former President Anote Tong became a globally recognized climate change advocate, tirelessly working to raise international awareness of the plight of his nation and other low-lying atoll countries. The government’s foreign policy is therefore geared towards building alliances with any nation willing to take meaningful climate action and securing funding for critical adaptation projects, such as building sea walls and protecting water supplies.

In the broader geopolitical arena, Kiribati’s foreign policy has navigated the strategic competition in the Pacific. For many years, the country recognized Taiwan, which provided significant development aid. However, in 2019, Kiribati switched its diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China, a move that reflected a shifting regional dynamic and Beijing’s growing influence. China has since become an important partner, offering infrastructure development and economic cooperation. Kiribati also maintains a treaty of friendship with the United States, which relinquished its historical claims to the Phoenix and Line Islands upon Kiribati’s independence. As a member of the Commonwealth of Nations and the United Nations, Kiribati uses these multilateral forums to advocate for its interests, particularly on issues of climate justice, ocean conservation, and sustainable development for small island developing states. Its foreign policy is a testament to the art of leveraging diplomacy to ensure national survival in the face of overwhelming challenges.

Back to top26. Administrative Divisions

The administrative divisions of the Republic of Kiribati are structured to govern a population spread across a vast and fragmented oceanic territory. The system operates on two main levels: the national government based in the capital, South Tarawa, and a system of local government that empowers individual island communities. The country does not have formal states or provinces like larger nations. Instead, for statistical and geographical purposes, the 33 islands are often grouped into the three main archipelagoes: the Gilbert Islands, the Phoenix Islands, and the Line Islands. However, these geographical groupings do not have any administrative function. The true local governance structure is centered on the islands themselves. Each of the 21 inhabited islands has its own island council, which serves as the fundamental unit of local government. This system ensures that even the most remote communities have a formal body for managing their own affairs.

The island councils are a key feature of Kiribati’s democracy, bringing governance down to the grassroots level. There are a total of 23 island councils, with some larger islands having more than one. These councils are established under the Local Government Act of 1984 and are responsible for a wide range of local services and administration. Their responsibilities include early childhood education, primary healthcare clinics, public sanitation, the maintenance of local roads and water supplies, and economic regulation at the local level. The councils are empowered to create their own by-laws and to estimate their own revenue and expenditure, giving them a degree of autonomy from the central government. The head of an island council is the Mayor (a title that replaced Chief Councillor), who, since a 2006 amendment, is now directly elected by the population of the island for a four-year term, enhancing local democratic accountability. The rest of the councillors are also elected by popular vote.

The central government’s oversight of these local bodies is managed by the Ministry of Internal and Social Affairs (MISA). While the island councils have a degree of freedom, MISA is responsible for the overall local government policy, providing assistance in drafting by-laws, approving budgets, and conducting audits to ensure proper financial management. The system blends modern democratic principles with traditional authority structures. The ‘unimane’ (village elders) continue to be highly respected and often have a reserved seat on the council as nominated members. This ensures that the traditional wisdom and consensus-building approach of the ‘maneaba’ (community meeting house) culture influences the formal decision-making process of the council. This administrative structure, focused on island councils, is a pragmatic solution for governing a nation of scattered and remote atoll communities, aiming to empower local people to take charge of their own development.

Back to Top27. Economy & Commodities

The economy of Kiribati is small, fragile, and heavily constrained by its unique and challenging geography. Classified by the United Nations as one of the world’s Least Developed Countries, its economic base is narrow, and it faces significant obstacles such as its remoteness from international markets, limited natural resources, and a workforce scattered across vast distances. The economy is largely dependent on two main sources of external income: revenue from the sale of fishing licenses and international aid. The nation’s vast and resource-rich exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is its most significant asset. Foreign fishing fleets, primarily from countries like Japan, South Korea, and the United States, pay substantial fees for the right to fish for tuna and other species in Kiribati’s waters. This revenue from fishing licenses is the largest source of government income and is critical for funding public services.

The domestic economy is primarily subsistence-based, with a large portion of the population engaged in small-scale agriculture and fishing to meet their own needs. The most important agricultural commodity is copra, which is the dried meat of coconuts. For many families in the outer islands, the production and sale of copra is the only source of cash income. Other local commodities include breadfruit, pandanus, and taro, which are staples of the local diet. The formal sector of the economy is small and is dominated by the government, which is the largest employer. Private sector activity is limited, concentrated mainly in retail trade, small-scale construction, and services in the capital, South Tarawa. There is very little manufacturing, and the country relies heavily on imported goods for almost all of its food, fuel, and manufactured products, leading to a persistent trade deficit.

International aid and remittances from I-Kiribati working abroad, particularly as seafarers on international merchant ships, are also vital components of the national economy. Development assistance from partners like Australia, New Zealand, the Asian Development Bank, and the World Bank funds critical infrastructure projects, education, and healthcare. To provide a buffer against the volatility of its limited income sources, Kiribati established a sovereign wealth fund in 1956, the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund (RERF). This fund was originally capitalized with revenues from phosphate mining on the island of Banaba before the deposits were exhausted around the time of independence. The careful management of the RERF provides an important source of supplementary income for the government budget. The long-term economic challenges for Kiribati are immense, focusing on developing sustainable industries like tourism, improving public financial management, and adapting to the severe economic impacts of climate change.

Back to Top28. Science and Technology

The landscape of science and technology in Kiribati is one of stark contrasts, where ancient, sophisticated traditional knowledge systems coexist with the immense challenges of adopting modern technology in a remote and resource-limited environment. For centuries, the I-Kiribati people have been masters of indigenous science and technology, particularly in the realm of navigation. Traditional navigators, known as ‘te-tia-borau’, possessed an incredibly detailed and complex understanding of the natural world. They could navigate the vast, featureless expanse of the Pacific Ocean by memorizing star charts, observing the patterns of ocean swells and waves as they refracted around atolls, reading the color and temperature of the water, and understanding the flight paths of specific birds. This was not magic; it was a deeply empirical science passed down through generations, allowing them to precisely locate tiny, low-lying islands separated by hundreds of kilometers of open ocean. This traditional ecological knowledge also extended to fishing, agriculture, and construction, enabling a sustainable existence on the atolls.

In the modern era, the adoption of contemporary science and technology is a critical priority for Kiribati’s development, but it is fraught with challenges. The country’s remoteness, small population, and limited financial resources make it difficult to build and maintain modern scientific infrastructure. There is a heavy reliance on international aid and expertise for technological development. A key focus area is telecommunications. For many years, Kiribati relied solely on expensive and high-latency satellite connections for its link to the outside world. This resulted in extremely slow and costly internet access, hampering business, education, and government services. Recently, however, significant progress has been made. The liberalization of the telecom market and projects supported by the World Bank and other partners are improving connectivity. The move towards submarine fiber-optic cables and the use of new-generation satellite technology are beginning to bring faster and more affordable internet to the country, at least in the capital, South Tarawa.

The most urgent application of science and technology in Kiribati today is in the fight against climate change. The existential threat of sea-level rise requires a science-based approach to adaptation and resilience. The government and its international partners are utilizing modern science and technology to address this challenge. This includes using satellite imagery and GPS mapping to monitor coastal erosion and inundation, conducting hydrological studies to protect fragile freshwater lenses from saltwater intrusion, and researching climate-resilient crops and infrastructure designs. There is a growing effort to integrate modern climate science with traditional ecological knowledge, recognizing that the deep understanding of the local environment held by the I-Kiribati people is a valuable resource in developing effective adaptation strategies. The future of science and technology in Kiribati will depend on its ability to bridge this gap, leveraging global innovations to address its unique local challenges while preserving the invaluable scientific heritage of its ancestors.

Back to Top29. Philosophy

The traditional philosophy of Kiribati is a rich and intricate worldview, deeply woven into the fabric of daily life, social structure, and the people’s relationship with a challenging atoll environment. It is not a system of abstract, written doctrines but a living philosophy expressed through myth, custom (‘te katei’), social values, and a profound understanding of the natural world. At its core is a belief system that does not draw a sharp distinction between the spiritual and physical realms. The world is understood to be inhabited by various spirits (‘anti’), including ancestral spirits and spirits of nature, which can influence human affairs. This worldview fosters a deep respect for the ancestors and the unseen forces that govern the world. Legends and myths, such as the creation stories involving the gods Nareau the Elder and Nareau the Younger, provide a cosmological framework for understanding the origins of the islands, the sea, the sky, and humanity itself. These stories serve as moral and ethical guides, teaching the values of cooperation, respect, and the importance of maintaining balance within the community and with the environment.

A central concept in the I-Kiribati social philosophy is the ‘maneaba’. The maneaba is the community meeting house, a large, open-sided structure that is the physical and social heart of every village. However, it is much more than just a building; it is the embodiment of the community’s collective identity and its commitment to consensus-based governance. The maneaba is where all important community decisions are made, disputes are resolved, and celebrations are held. The philosophy of the maneaba is one of inclusivity and deliberation, where elders (‘unimane’) guide discussions, and every member of the community has a voice. The goal is not to win an argument but to reach a consensus that preserves social harmony (‘te raoi’). This emphasis on community cohesion, shared responsibility, and the peaceful resolution of conflict is a fundamental tenet of the I-Kiribati worldview.

Other key philosophical values include a profound respect for elders, the importance of family and kinship (‘te kainga’), and a complex understanding of honor and social standing. The unimane are the keepers of traditional knowledge, history, and wisdom, and their guidance is sought on all important matters. The strength of the extended family provides the primary social safety net and defines an individual’s place in the world. Life on a resource-scarce atoll has also instilled a philosophy of self-reliance, ingenuity, and a deep, cyclical understanding of time and nature. The I-Kiribati possess an intimate knowledge of the sea, the stars, and the seasons, which has been essential for survival. This traditional philosophy, while now coexisting with Christianity, continues to shape the identity, values, and social interactions of the people of Kiribati, providing a resilient foundation in the face of modern challenges.

Back to Top30. Cultural Etiquette

Navigating the cultural etiquette of Kiribati requires an appreciation for a society that is deeply communal, respectful, and rooted in tradition. The I-Kiribati people are known for their warmth, friendliness, and generosity, but observing local customs (‘te katei’) is a key way to show respect and ensure positive interactions. The concept of community is paramount, and visitors will find that life is lived very publicly, especially in the outer islands. It is important to greet people with a friendly “Mauri” (hello/welcome). A simple smile and a nod are always appreciated. When entering a village or approaching a ‘maneaba’ (the community meeting house), it is best to do so with a respectful and unassuming demeanor. The maneaba is the heart of the village, and visitors should always ask for permission before entering. If invited into a maneaba, one should sit cross-legged and observe the proceedings quietly unless invited to speak.

Respect for elders is a cornerstone of I-Kiribati culture. The ‘unimane’ (village elders) are held in the highest esteem, and their opinions and decisions carry great weight. When interacting with elders, it is important to be polite and deferential. It is considered rude to stand or walk past a seated elder without stooping slightly as a sign of respect. Gift-giving is not a major part of initial interactions, but small, thoughtful gifts from your home country can be a nice gesture if you are being hosted by a family. It is also important to be mindful of dress code. While Kiribati is hot and humid, modest dress is the norm. Both men and women should ensure their shoulders and knees are covered when in public, especially in villages and when visiting churches. Beachwear should be reserved for the beach or tourist resorts. Being loud, boisterous, or openly displaying anger or frustration is considered poor form and disrupts the social harmony (‘te raoi’) that is highly valued.

Hospitality is a point of pride, and visitors may find themselves invited into a local home for a meal. Accepting such an invitation is a wonderful opportunity to experience local culture. When entering a home, it is customary to remove your footwear. You will likely be offered the best food and seating. It is polite to accept what is offered and to eat with your right hand. Complimenting the food is always appreciated. Be prepared for a diet that consists mainly of fish, rice, coconut, and local starches like breadfruit and taro. Taking photographs of people without asking for their permission is considered impolite. Always ask first, and be gracious if they decline. By approaching with humility, a willingness to learn, and a genuine respect for the local way of life, visitors to Kiribati will be rewarded with an incredibly warm and authentic cultural experience.

Back to Top31. Sports and Recreation

Sports and recreation in Kiribati are a vibrant mix of traditional pastimes that reflect the nation’s unique culture and environment, alongside popular modern sports that ignite community passion. Traditional sports are often linked to community gatherings and tests of skill. One such activity is ‘te-ano’, a game played with a heavy woven ball made from pandanus leaves. Two teams line up facing each other and attempt to keep the ball in the air by hitting it with their hands or feet, scoring points when the opposing team drops it. Another traditional activity is canoe racing, which showcases the incredible seamanship and boat-building skills of the I-Kiribati people. Races in outrigger canoes are a highlight of national celebrations and are a source of great village pride. These traditional sports are not just for entertainment; they are a way of preserving cultural heritage and reinforcing community bonds.

Among modern sports, volleyball is arguably the most widely played and popular recreational activity. In nearly every village, from the bustling capital of South Tarawa to the most remote outer islands, you will find a volleyball court, often a simple patch of sand with a net. The sport is played with great enthusiasm by people of all ages and genders, and it is a central feature of daily social life, providing a fun way for communities to come together in the evenings. Football (soccer) is also very popular, especially among the youth, although the lack of large grassed areas presents a challenge. The national football team competes in regional Pacific competitions, and the sport is followed with great interest. Rugby is another sport that is gaining a following in the country.

Given its geography, it is no surprise that water-based activities are at the heart of recreation in Kiribati. The pristine lagoons and surrounding ocean offer some of the most spectacular and untouched fishing grounds in the world. Sport fishing is a major draw for the few tourists who make it to Kiribati, with Kiritimati (Christmas Island) being a world-renowned destination for bonefishing and fly-fishing. The sheer abundance and size of the bonefish, along with giant trevally and other species, make it a bucket-list location for serious anglers. The clear, warm waters also provide incredible opportunities for snorkeling and diving, particularly in the Line and Phoenix Islands, where the coral reefs are vibrant and teeming with life. For locals, fishing is not just a recreation but a fundamental part of life, and spending time on or in the water is the most natural form of leisure.

Back to Top32. Environmental Concerns

The Republic of Kiribati is on the absolute front line of the global climate crisis, facing a set of environmental challenges that pose an existential threat to the nation’s future. The most pressing and overwhelming concern is sea-level rise. As a nation composed almost entirely of low-lying coral atolls, with an average elevation of just two meters above sea level, even a modest increase in the global sea level has catastrophic consequences. The rising waters lead to more frequent and extensive coastal inundation, especially during king tides and storm surges. This saltwater intrusion contaminates the country’s scarce freshwater resources, seeping into the underground freshwater lenses that are the primary source of drinking water for the population. It also destroys staple food crops like breadfruit and taro, which are unable to tolerate the increased salinity in the soil, thereby threatening the nation’s food security.

Coastal erosion is another severe and visible consequence of climate change. The combination of rising seas and changing weather patterns, which bring stronger storms and altered wave dynamics, is rapidly eroding the shorelines of Kiribati’s atolls. This loss of land is not a future projection; it is a current reality. Entire villages have already had to relocate further inland, and critical infrastructure, including roads, hospitals, and homes, is constantly at risk of being washed away. The government and local communities are engaged in a constant battle to protect their land, building sea walls and planting mangroves, but these measures are often temporary solutions against the relentless power of the ocean. The environmental stress also has a profound impact on the nation’s coral reefs. Rising sea temperatures cause coral bleaching, which can kill the reefs, destroying the vital ecosystems that protect the islands from wave energy and serve as the primary habitat for the fish that the I-Kiribati people depend on for their protein and livelihoods.

Beyond the climate crisis, Kiribati also faces more conventional environmental challenges related to waste management and pollution, particularly in the densely populated capital of South Tarawa. A growing population, combined with a shift towards a consumer economy based on imported goods, has led to a significant increase in solid waste. The limited land area makes it extremely difficult to find space for landfills, and the disposal of waste, especially non-biodegradable plastics, is a major problem. Pollution from sewage and household waste also threatens the health of the surrounding lagoons and marine life. In response to these immense challenges, Kiribati has become a leading voice in international climate advocacy, pleading with the global community to take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Domestically, the government is focused on implementing adaptation strategies, captured in its Joint Implementation Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management, as it fights for the very survival of its homeland.

Back to Top33. Marriage & Courtship

In Kiribati, marriage is a deeply significant social institution that binds not just two individuals, but two extended families (‘kainga’). Traditional courtship and marriage customs, while evolving, continue to place a strong emphasis on family involvement, community approval, and the preservation of social harmony. Historically, marriages were often arranged by families, who would consider factors like social standing and the ability to work and contribute to the family’s well-being. Today, while young people have more freedom to choose their own partners, family consent remains a crucial step. Courtship is typically a discreet and modest affair. Public displays of affection are not common. A young man interested in a woman will often express his intentions through an intermediary, such as a relative, who will approach the woman’s family. This formal approach shows respect and seriousness of intent.

Once a couple decides to marry and both families have given their blessing, a series of traditional customs and negotiations may take place. This can involve the groom’s family presenting gifts to the bride’s family as a sign of respect and to formalize the union. The wedding itself is a major community event, often celebrated in the ‘maneaba’ (community meeting house). The celebration involves a Christian church service, reflecting the strong influence of religion in modern Kiribati, followed by a large feast for the entire village. The feast is a vibrant affair with traditional music, dancing, and an abundance of food, including fish, pork, rice, and local staples. The marriage solidifies the bond between the two families, creating a new network of obligations and support that is central to the resilience of I-Kiribati society.

Back to Top34. Work Opportunities

Work opportunities in Kiribati are limited and heavily influenced by the country’s small, developing economy and its unique geographical constraints. The public sector is by far the largest formal employer in the nation. The government of Kiribati, including its various ministries, departments, and state-owned enterprises, provides the majority of salaried jobs. These positions are concentrated in the capital, South Tarawa, and range from administrative and clerical roles to professional positions in fields like education, healthcare, and public administration. For many I-Kiribati, securing a government job is seen as the most stable and desirable form of employment, offering a regular income and benefits that are rare in the private sector. However, the capacity of the public sector to absorb the country’s young and growing labor force is limited, leading to high rates of unemployment and underemployment.

The private sector in Kiribati is small and underdeveloped, centered primarily on retail trade, small-scale construction, and services catering to the local population in South Tarawa. Opportunities in the formal private sector are scarce. Outside the capital, in the remote outer islands, the economy is almost entirely based on subsistence living. Families rely on fishing and the cultivation of crops like coconut, breadfruit, and pandanus to survive. The only significant source of cash income for many in the outer islands is the production of copra (dried coconut meat), which is sold to the government for export. This reliance on a single commodity makes these communities vulnerable to price fluctuations and environmental factors.

Given the limited opportunities at home, a significant and vital source of employment for I-Kiribati men is the international maritime industry. For decades, Kiribati has maintained a well-regarded fisheries and marine training center, producing skilled seafarers who are sought after by international shipping companies, particularly in Germany. The remittances sent home by these seafarers are a critical source of income for their families and for the national economy as a whole. For expatriates, work opportunities are extremely limited and are almost exclusively found in internationally funded development projects, diplomatic missions, or in highly specialized technical roles where local expertise is not available. These positions are typically with organizations like the United Nations, the World Bank, or aid agencies from countries like Australia and New Zealand. Finding work as an expatriate generally requires securing a position before arriving in the country, as the government prioritizes employment for its own citizens.

Back to Top35. Education

The education system in Kiribati is a fundamental pillar of the nation’s development strategy, aimed at building the human capital needed to navigate the country’s unique challenges. The system is largely based on the British model and is managed by the Ministry of Education. The government provides for nine years of compulsory education, which includes six years of primary school and three years of junior secondary school. The language of instruction is primarily Gilbertese (I-Kiribati) in the early years of primary school, with a gradual transition to English, which becomes the main medium of instruction in junior secondary school and beyond. This bilingual policy is designed to preserve the national language and culture while also equipping students with the English language skills necessary for higher education and international opportunities. After completing junior secondary school, students who achieve a high enough score on a national examination can proceed to senior secondary school. Others may enroll in vocational training programs that provide practical skills in areas like carpentry, mechanics, and maritime studies. The most prestigious of these is the Marine Training Centre, which has a global reputation for producing skilled seafarers for the international merchant navy. For the top academic students, the King George V and Elaine Bernacchi School in Tarawa is the premier government senior secondary school, preparing them for higher education abroad. The education system faces immense challenges, including a lack of resources, a shortage of qualified teachers, and the logistical difficulty of providing equitable education across a nation of scattered and remote atolls. Despite these obstacles, Kiribati has achieved a high literacy rate, reflecting the high value that I-Kiribati society places on education as a pathway to a better future for their children.

Back to Top36. Communication & Connectivity

Communication and connectivity in Kiribati present a significant challenge and a critical area of development for the remote island nation. For decades, the country’s immense geographical dispersion and isolation meant that it was one of the least connected places on Earth, relying solely on expensive and high-latency satellite links for all its international communication. This resulted in extremely slow and costly internet and telephone services, which were largely confined to the capital, South Tarawa. The difficulty in communication created a major barrier to economic development, education, healthcare, and even basic social connection between families separated by the vast ocean. In the outer islands, connectivity was often non-existent, with communities relying on high-frequency radio for essential communication.

In recent years, the telecommunications landscape has begun to transform, although a significant digital divide remains. The market was liberalized, leading to the entry of new providers and increased investment in infrastructure. The dominant mobile operator is Vodafone Kiribati (formerly ATHKL), which has been working to expand its network. 3G and 4G/LTE mobile services are now available in the urban center of South Tarawa and on Kiritimati (Christmas) Island, providing residents in these areas with access to mobile broadband. This has led to a rapid increase in internet usage, with social media platforms like Facebook becoming a vital tool for communication and staying in touch with relatives working as seafarers abroad. However, outside of these main population centers, mobile coverage is sparse and often limited to 2G, if it exists at all.

For travelers, staying connected in the capital is relatively straightforward. It is possible to purchase a local prepaid SIM card from a provider like Vodafone to get access to mobile data. Wi-Fi is available in major hotels and some cafes in South Tarawa, but it can be slow and less reliable than in more developed countries. In the outer islands, visitors should expect to be largely disconnected from the internet. Some island council offices may have a basic satellite internet connection, but this is not generally available for public use. The ongoing efforts to connect Kiribati to a submarine fiber-optic cable promise a future of faster and more affordable internet, which would be a game-changer for the nation. Until then, communication in Kiribati remains a tale of two worlds: the increasingly connected capital and the isolated tranquility of the outer islands.

Back to Top37. National Symbols

The national symbols of Kiribati are a rich and evocative representation of the nation’s unique geography, culture, and aspirations. The most prominent and celebrated symbol is the national flag, which was designed by Sir Arthur Grimble, a British colonial administrator, in 1932 for the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony and was readopted upon independence in 1979. The flag’s design is both beautiful and deeply symbolic. The top half features a magnificent yellow frigatebird (‘te eitei’) soaring over a rising sun. The frigatebird is a master of the skies and symbolizes power, freedom, and authority. The rising sun, with its 17 rays, represents the 16 Gilbert Islands and Banaba, and it also alludes to Kiribati’s position on the equator, where the sun is at its strongest. The bottom half of the flag consists of three blue and three white wavy horizontal bands, which symbolize the Pacific Ocean, the lifeblood of the nation, and the three island groups: the Gilbert, Phoenix, and Line Islands.

The coat of arms of Kiribati mirrors the design of the flag, featuring the same soaring frigatebird and rising sun over the ocean waves. Below the shield is a ribbon bearing the national motto: “Te Mauri, Te Raoi ao Te Tabomoa.” This translates from the Gilbertese language to “Health, Peace and Prosperity,” a powerful expression of the nation’s fundamental aspirations for its people. The coat of arms, like the flag, encapsulates the core elements of the I-Kiribati identity: their connection to the sea, their freedom as a sovereign people, and their hopes for a peaceful and healthy future. These emblems are used on official government documents and are a source of immense national pride.

Beyond the official state symbols, Kiribati’s unique natural environment provides other important national icons. While not officially designated, the pandanus tree (screwpine) is a vital cultural symbol. This versatile tree is central to I-Kiribati life; its fruit is a staple food source, its leaves are used for weaving everything from mats and baskets to the sails of traditional canoes, and its wood is used for construction. In terms of fauna, the frigatebird, featured so prominently on the flag, is considered the national bird. The waters surrounding the islands are teeming with life, and animals like the sea turtle and the manta ray are powerful symbols of the ocean’s majesty and importance. These symbols, from the soaring frigatebird to the life-giving pandanus, collectively paint a picture of a nation that is deeply proud of its connection to the sky, the sea, and the resilient culture that has allowed it to thrive in the heart of the Pacific.

| Category | Symbol |

|---|---|

| Official Symbols | National Flag, Coat of Arms |

| Motto | “Te Mauri, Te Raoi ao Te Tabomoa” (Health, Peace and Prosperity) |

| Cultural Symbols | Maneaba (community meeting house), Outrigger canoe, Pandanus tree, Thatched roof ‘buia’ (hut) |

| National Flora | Pandanus (Screwpine) – unofficially, due to its cultural importance |

| National Fauna | Frigatebird (‘Fregata minor’ – National Bird), Bonefish (symbol of the world-class fishery) |

38. Tourism

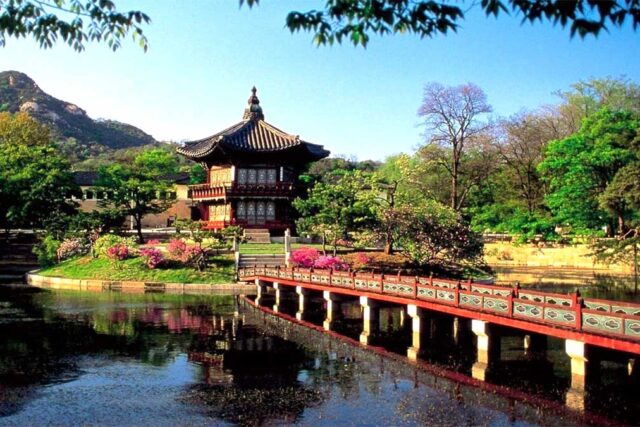

Tourism in Kiribati is an experience for the truly intrepid traveler, offering a journey to one of the most remote and least visited countries on Earth. It is a destination that rewards visitors not with luxury resorts and polished attractions, but with unparalleled authenticity, pristine natural beauty, and a deep immersion into a unique and resilient atoll culture. The country’s tourism is centered on its incredible marine environment and its rich cultural heritage. The main draw for the majority of international visitors is the world-class fishing, particularly on Kiritimati (Christmas) Island. Kiritimati is legendary among fly-fishing and sport-fishing enthusiasts as arguably the best bonefishing destination in the world. The vast, shallow flats of its lagoon teem with bonefish, giant trevally, and triggerfish, offering an angler’s paradise. The pristine and largely untouched nature of the fishery makes it a bucket-list destination for those seeking a truly wild and challenging fishing adventure.

Beyond fishing, Kiribati’s other great tourism asset is its spectacular underwater world. The coral reefs, especially in the remote Phoenix and Line Islands, are among the most pristine on the planet. The Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) is a vast marine wilderness, a UNESCO World Heritage site that is a haven for divers and researchers. While access is extremely limited and requires joining a dedicated liveaboard expedition, those who make the journey are rewarded with vibrant coral gardens, massive schools of fish, and encounters with sharks, manta rays, and turtles in a virtually untouched ecosystem. For those interested in history, the atoll of Tarawa offers a poignant journey into the past. It was the site of one of the most brutal battles of World War II’s Pacific campaign, and remnants of the conflict, including coastal defense guns, bunkers, and sunken landing craft, can still be seen, serving as a somber reminder of its history. The real heart of a trip to Kiribati, however, is the opportunity to experience the authentic I-Kiribati way of life, visit a local village, and be welcomed into the community with warmth and generosity.

Back to Top39. Visa and Entry Requirements

Navigating the visa and entry requirements for Kiribati requires careful advance planning due to the country’s remoteness and the limited number of diplomatic missions. The visa policy of Kiribati grants visa-free access to citizens of a number of countries for short stays. However, unlike many other nations, a significant number of nationalities are required to obtain a visa before arrival. Citizens of countries that are part of the visa waiver agreement can typically enter for tourism or business for a period of up to 30 days, provided they meet the standard entry requirements. It is absolutely essential for all prospective travelers to check the most current visa regulations for their specific nationality with the Kiribati Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Immigration or the nearest Kiribati honorary consulate well in advance of their planned trip, as policies can change.

For those who do require a visa, the application must be submitted and approved before traveling to Kiribati. The process generally involves completing a visa application form, providing a valid passport with at least six months of validity beyond the intended stay, submitting passport-sized photographs, and paying the required visa fee. The processing time for a visa can take several weeks, so it is crucial to apply with ample time to spare. Independent of visa requirements, all travelers arriving in Kiribati must be able to present proof of an onward or return ticket. They must also be able to demonstrate that they have sufficient funds to support themselves for the duration of their stay. This is a strict requirement, and airlines may deny boarding to passengers who cannot provide this evidence.

Upon arrival, all visitors must comply with Kiribati’s health and customs regulations. Travelers must present a COVID-19 vaccination certificate. While there are no mandatory tests on arrival for asymptomatic travelers, anyone showing symptoms is encouraged to get tested at a local hospital. It is also wise to check for any other health advisories, such as the need for a yellow fever vaccination certificate if arriving from an endemic country. Customs regulations are strict, particularly regarding the importation of plants, animal products, firearms, and pornography. Travelers should declare all food and biological items to biosecurity officers. Given the limited and sometimes sporadic nature of international flights to Kiribati, ensuring all travel documents are in perfect order is a critical step to a successful and stress-free journey.

Back to Top40. Useful Resources

- Kiribati Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Immigration – For the most official and up-to-date visa and entry information.

- Kiribati National Tourism Office – Official government tourism website with information on destinations, culture, and activities.

- Air Kiribati – The national airline, for information on domestic flights between the islands.

- Australian Government (DFAT) – Kiribati Country Brief – Provides a reliable overview and travel advice.

- New Zealand High Commission to Kiribati – Offers consular information and travel advisories.

- World Bank – Kiribati – For in-depth data on the country’s economy and development.

- Pacific Islands Forum – Information on regional relations and issues affecting Kiribati.