Madagascar Travel Guide

Table of Contents

- 21. Brief History

- 22. Geography

- 23. Politics and Government

- 24. Law and Criminal Justice

- 25. Foreign Relations

- 26. Administrative Divisions

- 27. Economy & Commodities

- 28. Science and Technology

- 29. Philosophy

- 30. Cultural Etiquette

- 31. Sports and Recreation

- 32. Environmental Concerns

- 33. Marriage & Courtship

- 34. Work Opportunities

- 35. Education

- 36. Communication & Connectivity

- 37. National Symbols

- 38. Tourism

- 39. Visa and Entry Requirements

- 40. Useful Resources

21. Brief History

The history of Madagascar is as unique as its wildlife, a story defined by its remarkable isolation and a cultural fusion of Southeast Asia and Africa. Unlike the African mainland just 400 kilometers away, Madagascar was one of the last major landmasses on Earth to be settled by humans. The first arrivals were not from Africa, but were intrepid Austronesian peoples who crossed the vast Indian Ocean in outrigger canoes from the island of Borneo, likely around 350 BC to 550 AD. This foundational migration is the bedrock of Malagasy culture and is evident in the Malagasy language, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian family, and in agricultural practices like terraced rice cultivation. Over the subsequent centuries, these settlers were joined by Bantu-speaking migrants from East Africa, who intermingled with the existing population, primarily along the coastal regions. This dual origin created a distinctive Malagasy people and a complex system of ethnic groups and customs, blending Asian and African traditions in a way found nowhere else on the planet.

From the Middle Ages, a series of kingdoms and chieftaincies emerged across the island. European contact began in the 16th century with the arrival of the Portuguese, followed by the French and British, who established trading posts and vied for influence. For a time, the island also became a notorious haven for pirates. The pivotal moment in Malagasy political history came in the early 19th century with the rise of the Kingdom of Imerina in the central highlands. Under the ambitious ruler Andrianampoinimerina and his son, Radama I, the Merina kingdom began to unify the island. Radama I skillfully played the British and French against each other, inviting European missionaries and advisors to help modernize the army and administration, and established a written form of the Malagasy language. His successors, particularly the formidable Queen Ranavalona I, resisted European influence, but by the late 19th century, growing colonial ambitions led France to invade. After two Franco-Hova Wars, France officially annexed Madagascar in 1897, ending the Merina monarchy and ushering in an era of colonial rule.

French colonial rule lasted until the mid-20th century and was marked by resource exploitation and suppression of nationalist sentiment, most notably the bloody Malagasy Uprising of 1947. The path to independence was finally achieved peacefully on June 26, 1960. The post-independence era, however, has been fraught with political instability, with a series of coups, popular uprisings, and constitutional crises disrupting the country’s development. Leaders have oscillated between socialist-inspired policies and market-based reforms. Despite these political challenges and significant economic hurdles, the Malagasy people have maintained their incredibly rich and unique cultural heritage. Today, Madagascar stands as a nation grappling with the complexities of its past and the challenges of the present, from poverty to environmental degradation, while offering the world an unparalleled glimpse into a truly unique human and natural history. This journey from ancient settlers to a modern republic is essential to understanding the soul of this fascinating island nation.

22. Geography

Madagascar’s geography is as extraordinary as its history, earning it the nickname the “eighth continent.” As the world’s fourth-largest island, located in the Indian Ocean off the southeastern coast of Africa, its long isolation has created a landscape and ecosystem found nowhere else on Earth. The island’s topography is dominated by a central spine of highlands, or “haute plateaux,” that runs from north to south. This mountainous backbone, which has an average altitude of between 800 and 1,800 meters, dictates the country’s climate and divides it into distinct geographical regions. The highlands are characterized by terraced rice paddies that climb the hillsides, a testament to the island’s Southeast Asian cultural roots, as well as by rolling hills and rugged massifs. The highest peak, Maromokotro, rises to 2,876 meters in the Tsaratanana Massif in the north. The capital city, Antananarivo, is situated in the heart of these central highlands. This region experiences a temperate climate with a distinct rainy and dry season.

To the east of the central highlands lies a narrow coastal plain characterized by steep escarpments and home to the remnants of Madagascar’s once-vast lowland rainforests. This eastern flank faces the Indian Ocean and receives the most rainfall from the trade winds, resulting in a hot, humid climate and incredibly dense, lush vegetation. This is the epicenter of much of Madagascar’s famed biodiversity, with national parks like Andasibe-Mantadia and Ranomafana offering visitors the chance to see a dizzying array of unique flora and fauna, including numerous species of lemurs, chameleons, and orchids. The coastline here is relatively straight and is fringed by lagoons and canals, including the man-made Pangalanes Canal, which forms a navigable inland waterway stretching for hundreds of kilometers. This region’s unique climate and topography have made it a hotspot for eco-tourism and wildlife enthusiasts.

In stark contrast, the western and southern parts of the island lie in the rain shadow of the central highlands, creating much drier conditions. The west features broad plains and deciduous dry forests, which are home to some of Madagascar’s most iconic and otherworldly landscapes. This is where you will find the famous Avenue of the Baobabs near Morondava, a stunning dirt road lined with majestic, ancient baobab trees that create an unforgettable silhouette at sunrise and sunset. The coastline here is more indented, with mangrove swamps and beautiful beaches. The far south and southwest of the island transition into a unique semi-arid region known as the “spiny forest” or “spiny desert.” This area receives very little rainfall and is home to an extraordinary collection of drought-adapted plants, many of which are found nowhere else on the planet, including bizarre-looking, cactus-like Didiereaceae trees. This incredible geographical diversity, from rainforests to deserts, highlands to coasts, is what makes Madagascar a true continent in miniature.

23. Politics and Government

The political system of Madagascar is defined as a semi-presidential republic, a framework that has been in place through several constitutional revisions since the country gained independence from France in 1960. In this system, power is shared between a popularly elected President, who serves as the head of state, and a Prime Minister, who is the head of government. The President is elected by direct universal suffrage for a five-year term and is limited to two terms. The President holds significant executive powers, including being the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, having the authority to dissolve the National Assembly under certain conditions, and appointing the Prime Minister. However, the choice of Prime Minister must be nominated by the party or coalition that holds a majority in the lower house of parliament, creating a potential for power-sharing or political gridlock if the president and the parliamentary majority are from opposing political factions. This structure has been a contributing factor to the country’s history of political instability.

Legislative power in Madagascar is vested in a bicameral Parliament. The lower house is the National Assembly (Antenimierampirenena), whose members are directly elected by the public for five-year terms. The National Assembly is the principal legislative body, responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, and holding the government accountable. The upper house is the Senate (Antenimieran-doholona), which has a more advisory and reviewing role. A portion of the senators are elected by regional officials, while the remaining third are appointed directly by the President of the Republic. This structure is intended to provide representation for the country’s diverse regions and to serve as a chamber for legislative review, though the National Assembly holds the ultimate legislative authority. The judicial branch is constitutionally independent, with the High Constitutional Court being the final arbiter on the constitutionality of laws and the validity of elections, making it a powerful and often crucial player during times of political crisis.

Since its independence, Madagascar’s political landscape has been characterized by a high degree of volatility, marked by a series of popular uprisings, coups d’état, and constitutional changes. The period since the early 2000s has been particularly turbulent, including a major political crisis in 2002 and a coup in 2009 that led to several years of an internationally unrecognized transitional government and economic sanctions. The country returned to constitutional governance with elections in 2013, but the political scene remains highly personalized and fragmented, with political parties often forming around powerful individuals rather than coherent ideologies. This has made building stable, long-lasting coalitions difficult. For travelers, this political instability can occasionally lead to protests or disruptions, particularly in the capital, Antananarivo. Therefore, it is always wise to stay informed about the current political situation and follow the advice of local authorities and your country’s diplomatic mission while visiting.

24. Law and Criminal Justice

The legal system of Madagascar is primarily based on the French civil law model, a legacy of its colonial history, but it also incorporates elements of Malagasy customary law (dina). The foundation of the system is a hierarchy of written laws, including the Constitution, legislative statutes, and governmental regulations. Customary law, or dina, plays a significant and practical role, particularly in rural communities, where it is often used to resolve local disputes related to land, family matters, and even minor criminal offenses. These community-based agreements are officially recognized by the state and can be enforced by local authorities, reflecting a legal pluralism that adapts formal law to local contexts. However, the formal justice system, with its courts and legal professionals, is structured according to the French model. The judiciary is constitutionally independent, but in practice, it has faced significant challenges, including corruption, lack of resources, and political interference, which can undermine public trust in the system.

The national law enforcement bodies are the National Gendarmerie and the National Police. The Gendarmerie, which is part of the armed forces, is primarily responsible for policing rural areas and major highways, while the National Police are responsible for urban centers. For travelers, safety and security are major considerations. While Madagascar is an incredibly rewarding country to visit, it faces significant challenges with crime, exacerbated by widespread poverty. In the capital, Antananarivo, and other major towns, petty crime such as pickpocketing and bag-snatching is common, especially in crowded places like markets. More serious crime, including armed robbery and carjacking, also occurs. It is strongly advised not to walk around urban areas after dark. In rural areas, particularly in the south, banditry (dahalo) targeting cattle and sometimes travelers on remote roads is a serious concern. Therefore, it is crucial for visitors to exercise a high degree of caution, avoid displaying wealth, and seek up-to-date local advice on security conditions, especially before undertaking overland travel.

The criminal justice system in Madagascar struggles with significant capacity issues. The police and gendarmerie are often under-resourced and under-trained, which can hamper effective investigation and crime prevention. The court system is slow and overburdened, and pre-trial detention can be lengthy. Prisons are severely overcrowded and have poor conditions. For tourists who become victims of crime, reporting the incident to the police is necessary for insurance purposes, but they should be prepared for a slow and bureaucratic process. It is highly recommended to travel with a reputable tour operator who can provide security advice, reliable transportation, and assistance in case of an emergency. Despite these challenges, the vast majority of visitors have a trouble-free experience by taking sensible precautions and being aware of the risks. The Malagasy people themselves are generally warm and welcoming, and the security situation should not deter well-prepared and cautious travelers from experiencing this unique destination.

25. Foreign Relations

Madagascar’s foreign relations are primarily shaped by its historical ties, economic interests, and its strategic location in the Indian Ocean. As a former French colony, Madagascar maintains a strong, albeit complex, relationship with France. This connection is deeply embedded in the country’s political, economic, and cultural life. France is a major trading partner, a significant source of foreign aid and investment, and the home of a large Malagasy diaspora. The French language remains widely used in government and business, and the educational systems share historical links. However, the relationship is also marked by sensitive post-colonial issues, most notably the ongoing dispute over the sovereignty of the Glorioso Islands (Îles Glorieuses), a small archipelago administered by France but claimed by Madagascar. This issue remains a recurring theme in Malagasy diplomacy and a point of national pride.

As a developing nation, a central pillar of Madagascar’s foreign policy is its engagement with international organizations and development partners. The country is an active member of the United Nations, the African Union (AU), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). These platforms are crucial for Madagascar to voice its interests and to access technical and financial support for its development goals. Key international partners, including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Union, and countries like the United States, Japan, and Germany, provide substantial development assistance focused on areas such as poverty reduction, healthcare, education, and environmental conservation. However, this reliance on foreign aid has also made the country vulnerable to international pressure. Periods of political instability, particularly the 2009 coup, have led to the suspension of aid and diplomatic isolation, which has had severe impacts on the economy and the population.

In recent years, Madagascar has also sought to diversify its international partnerships, looking to strengthen ties with emerging economic powers. China, in particular, has become an increasingly important economic partner, with significant investment in infrastructure, mining, and commerce. This growing relationship is part of a broader trend across Africa and reflects Madagascar’s pragmatic approach to foreign policy, seeking investment and trade opportunities from a wide range of sources. The country’s unique biodiversity also plays a role in its diplomacy, as it engages with international conservation organizations and partners on efforts to protect its globally significant ecosystems. Balancing the need for economic development with the imperative of environmental protection is a key challenge that shapes many of its international relationships and is a central theme in its engagement with the global community.

26. Administrative Divisions

The administrative divisions of Madagascar have evolved over time, reflecting changes in political structure and development strategies. Since 2021, the primary level of administrative division consists of 23 regions (faritra). These regions replaced the six former provinces (faritany), which were officially dissolved in 2009 in a bid to decentralize power and bring governance closer to the people. Each of the 23 regions is headed by a Regional Chief, who is appointed by the central government. The regions are intended to be the main framework for economic planning and development, grouping together areas with similar geographic and economic characteristics. For travelers, understanding the region you are in can be helpful, as each has a distinct character. For example, the Sava region in the northeast is famous as the “vanilla coast,” the Diana region in the north is home to the port city of Antsiranana (Diego Suarez) and beautiful beaches, while the Atsimo-Andrefana region in the southwest contains the city of Toliara and the unique spiny forest ecosystem.

Below the regional level, the country is further subdivided into districts. There are 114 districts in total, and each region is composed of several districts. The districts serve as an intermediary level of administration between the region and the more local communes. This structure is part of the state’s effort to manage its vast and often difficult-to-reach territory. The heads of these districts are also appointees of the central government, ensuring a chain of command from the capital, Antananarivo, down to the local level. This centralized appointment system means that while the structure is decentralized geographically, political power remains largely concentrated with the national government. For the average visitor, the district level is less prominent than the region or the specific towns and parks they might be visiting.

The most fundamental unit of local governance in Madagascar is the commune. There are over 1,600 communes across the country, which can be either urban or rural. Unlike the heads of regions and districts, the mayor and council of each commune are directly elected by local citizens. This makes the commune the primary level of democratic participation and local self-governance. The communes are responsible for providing basic public services, managing local markets, and maintaining local records. However, most communes, especially in rural areas, suffer from a severe lack of financial resources and institutional capacity, which limits their ability to effectively serve their populations. This tiered system of regions, districts, and communes forms the complex administrative map of modern Madagascar, reflecting an ongoing effort to balance centralized control with local governance in a large and diverse nation.

27. Economy & Commodities

The economy of Madagascar is largely based on agriculture, mining, and tourism, but it is classified as a developing economy and faces significant challenges, including political instability, poor infrastructure, and high levels of poverty. The agricultural sector is the backbone of the economy, employing approximately 80% of the population and accounting for a significant share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Most farming is subsistence-based, with rice being the staple food and the most important crop, cultivated in picturesque terraced paddies in the central highlands and in coastal areas. However, Madagascar is also a major global producer of several high-value cash crops. The most famous of these is vanilla. The Sava region in the northeast is the world’s leading producer of high-quality Bourbon vanilla, and the commodity is a crucial source of foreign exchange, though its price is subject to extreme volatility. Other key agricultural exports include cloves, lychees, and cocoa.

The mining and extractive industries represent another vital component of the Malagasy economy, holding significant potential for future growth. The country is endowed with a rich and diverse array of mineral resources. It is a leading producer of industrial minerals like graphite and chromite. More recently, large-scale mining projects have been established to extract nickel and cobalt, primarily driven by foreign investment. Madagascar is also famous for its gemstones, with deposits of sapphires, rubies, and emeralds attracting miners and traders from around the world, although much of this trade operates in the informal or artisanal sector. The development of the mining sector is a key government priority for boosting exports and economic growth, but it also raises significant environmental and social concerns that need to be carefully managed to ensure the benefits are shared equitably and the country’s unique ecosystems are protected.

The services sector, particularly tourism, is a major source of foreign currency and employment. The country’s unparalleled biodiversity, including its iconic lemurs and unique landscapes like the Avenue of the Baobabs, makes it a dream destination for eco-tourists and wildlife enthusiasts. However, the tourism sector is highly sensitive to the country’s political stability and infrastructure challenges. Poor road conditions, limited domestic flight options, and safety concerns can be significant deterrents. The textile and apparel industry is another important export-oriented sector, producing garments for major international brands, largely through export processing zones. Despite this potential, the overall economy remains fragile. The national currency is the Malagasy Ariary (MGA). Visitors should be aware that credit cards are only accepted in high-end hotels and some businesses in the capital, and that Madagascar is predominantly a cash-based economy. For most transactions, especially in rural areas, carrying a sufficient amount of local currency is essential.

28. Science and Technology

The landscape of science and technology in Madagascar is one of stark contrasts, characterized by world-class biodiversity research coexisting with significant challenges in infrastructure and broad technological adoption. The country’s most prominent contribution to global science is in the field of biology, ecology, and conservation science. As a globally recognized biodiversity hotspot, with over 80% of its species found nowhere else on Earth, Madagascar is a living laboratory for scientists. For decades, it has attracted researchers from around the world who come to study its unique flora and fauna, from its famous lemurs and chameleons to its bizarre spiny forests and medicinal plants. Several internationally renowned research stations operate in the country, often in collaboration with Malagasy universities and conservation organizations. The ValBio Research Center near Ranomafana National Park and the Madagascar Biodiversity Center are key institutions that conduct vital research and play a crucial role in training the next generation of Malagasy scientists.

In the field of medical science, Madagascar has a long tradition of studying and utilizing its rich botanical resources. The Malagasy Institute for Applied Research (IMRA) was founded to study the country’s medicinal plants and has been involved in developing treatments from natural sources. This focus on ethnobotany and phytochemistry is a significant area of scientific inquiry. However, beyond the specialized field of biodiversity research, the broader science and technology infrastructure in Madagascar faces considerable limitations. The country’s universities and research institutions are often underfunded, which constrains their ability to conduct advanced research in other fields like physics, engineering, or chemistry. Investment in research and development (R&D) remains low, and there is a significant “brain drain” of talented Malagasy scientists who seek better opportunities abroad.

When it comes to modern technology adoption, the picture is also mixed. Mobile phone penetration has grown rapidly, as in much of Africa, providing a crucial tool for communication and, increasingly, for mobile money services, which helps to overcome the lack of formal banking infrastructure. However, internet connectivity remains a major challenge. While access is available in the capital, Antananarivo, and other main towns, it is often slow, expensive, and unreliable. In rural areas, where the majority of the population lives, internet access is extremely limited or non-existent. This digital divide hampers opportunities for education, business, and access to information. There is a small but growing tech startup scene in Antananarivo, but it is constrained by these infrastructural hurdles. Overcoming these challenges by investing in education, research infrastructure, and affordable, widespread internet access is critical for Madagascar to harness the full potential of science and technology for its development.

29. Philosophy

The philosophical landscape of Madagascar is a rich and deeply ingrained cultural tapestry, primarily expressed through traditional beliefs, oral traditions, and a complex system of social etiquette rather than a formal, academic discipline in the Western sense. At the very core of Malagasy philosophy is the profound and pervasive respect for ancestors (razana). The belief is that ancestors are not truly gone but continue to exist as powerful intermediaries between the living and the divine creator, Zanahary. These ancestors are believed to watch over their living descendants, offering guidance and protection, but they can also cause misfortune if they are neglected or disrespected. This belief shapes almost every aspect of life, from daily rituals to major life events. The well-being of the community is seen as being directly linked to maintaining a harmonious relationship with the ancestors. This philosophical outlook emphasizes community over individualism, continuity over change, and the importance of upholding the traditions passed down through generations.

A key concept that flows from the reverence for ancestors is “fady,” a complex system of taboos or prohibitions that governs social conduct. Fady can be specific to a particular family, village, or entire ethnic group, and they dictate what can be eaten, what days are auspicious for certain activities, and how one should interact with certain people, places, or animals. For example, it might be fady for a certain clan to eat pork, or fady to point at a tomb. While these taboos may seem like mere superstitions to an outsider, they represent a deeply embedded ethical and philosophical framework for ordering society and maintaining a respectful balance with the spiritual and natural world. Violating a fady is believed to bring misfortune (tody), not just upon the individual, but upon the entire community. Understanding the concept of fady is essential for any traveler wishing to interact respectfully with local communities, especially in rural areas.

Another central pillar of Malagasy thought is the concept of “fihavanana,” a multifaceted term that encompasses ideas of kinship, friendship, solidarity, and good-will. It is the social glue that binds communities together. Fihavanana dictates that harmony and mutual support within the group are paramount, and open conflict or confrontation should be avoided whenever possible. It promotes a culture of cooperation, sharing, and consensus-building. While this can sometimes lead to a lack of directness that can be confusing for foreigners, it is rooted in a deep philosophical commitment to maintaining social peace. These core tenets—respect for ancestors, the observance of fady, and the practice of fihavanana—combine to create a unique Malagasy worldview. This philosophy is not found in dense academic texts, but is lived out daily in the proverbs, stories, and social interactions of the Malagasy people, offering a profound and different way of understanding the world and one’s place within it.

30. Cultural Etiquette

Navigating the cultural etiquette of Madagascar requires a deep appreciation for its unique blend of Southeast Asian and African influences, and a respect for the central role that ancestors, community, and tradition play in daily life. Politeness and respect, particularly towards elders, are paramount. When greeting someone, a handshake is common, but it’s important to be gentle. In many situations, especially in rural areas, it is considered a sign of respect to support your right forearm with your left hand when shaking hands or giving or receiving an object. This gesture signifies that you are offering something with your whole being. Using formal greetings is appreciated. “Salama” is a general, all-purpose greeting. Addressing elders with respect is crucial; you might hear terms like “tompoko” which is a versatile and polite term of address. Direct eye contact can sometimes be interpreted as confrontational, so a more gentle, indirect gaze is often the norm. A key principle is to always remain calm and patient; showing anger or impatience is considered highly impolite and will likely be counterproductive.

Understanding the concept of “fady” (taboos) is one of the most important aspects of cultural etiquette for a traveler. These taboos can vary significantly from one region or village to another and govern many aspects of life, from what foods can be eaten to which days are suitable for work or travel. While you are not expected to know all the local fady, it is crucial to be observant and willing to ask for guidance. For example, before entering a natural area, a forest, or approaching a tomb, it’s wise to ask your local guide if there are any fady associated with the place. Common fady might include not being allowed to point at a tomb, not being allowed to wear a certain color in a sacred forest, or prohibitions against certain foods. Showing that you are aware of the concept and are willing to respect local customs will earn you enormous goodwill and is essential for positive interactions, particularly in rural communities. Your guide is your best resource for navigating these complex but vital cultural rules.

Hospitality is a cornerstone of Malagasy culture, and you may be invited to share a meal. If so, it is a great honor. It is customary to bring a small gift, but it should be something simple. A small amount of money given discreetly, some bread, or some rum are often appropriate. When eating, it is polite to accept what is offered and to try a little of everything. The oldest person is often served first. In conversation, communication tends to be indirect. A direct “no” is often considered impolite, so people may use more ambiguous or non-committal answers to avoid causing offense. This is related to the concept of “fihavanana,” the importance of maintaining harmony and good relations. It’s also important to be mindful when taking photographs. Always ask for permission before taking a picture of a person, and be particularly sensitive around tombs and other sacred sites, where photography may be fady. By approaching every interaction with humility, patience, and a genuine desire to learn and respect, travelers can navigate the rich cultural landscape of Madagascar and be rewarded with warm and authentic experiences.

31. Sports and Recreation

Sport in Madagascar is a passionate affair, with a few key sports capturing the heart of the nation. By far the most popular sport is football (soccer). The national team, known as the “Barea” (a species of zebu cattle), ignited unprecedented national pride and unity during their surprising and heroic run to the quarterfinals of the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations. This achievement brought the entire country to a standstill and cemented football’s place as the number one sport. Local league matches are followed with enthusiasm, and on any given day, you will see children and adults playing football in fields and streets across the island. Another hugely popular sport is rugby union. It is particularly popular in the capital, Antananarivo, and the central highlands, where it has a long history. The national rugby team, the “Makis” (the Malagasy word for lemur), is one of the strongest in Africa, and their matches draw large, passionate crowds. The physicality and team spirit of rugby resonate strongly in Malagasy culture.

Beyond the top two team sports, Madagascar has its own unique traditional sport and has shown prowess in several individual disciplines. The national sport of Madagascar is “savika,” a spectacular and daring form of bare-handed bull wrestling. Practiced mainly by the Betsileo ethnic group in the southern highlands, savika involves young men testing their courage and skill by clinging to the hump of an angry zebu cattle for as long as possible. It is a dangerous but culturally significant rite of passage and a major spectacle at local festivals. In more conventional sports, “pétanque,” the French game of boules, is incredibly popular and is played by people of all ages in squares and parks across the country. Madagascar has produced world champions in pétanque, and it is a social and competitive pastime that visitors can easily observe and even participate in. Track and field athletics are also followed, and the country regularly participates in the Indian Ocean Island Games and the Olympic Games.

Recreation in Madagascar is largely defined by its incredible natural environment, though access can be challenging due to infrastructure limitations. For locals, recreation often involves community gatherings, music, and dance. For visitors, the opportunities for outdoor recreation are immense. The country is a world-class destination for hiking and trekking, with numerous national parks like Isalo, Andringitra, and Andasibe offering trails through stunning and diverse landscapes, from sandstone canyons to dense rainforests. The opportunity to see unique wildlife, especially lemurs, in their natural habitat is the primary recreational draw for most tourists. The coastline also offers significant recreational potential. The waters around islands like Nosy Be in the northwest are ideal for scuba diving and snorkeling, with healthy coral reefs and diverse marine life. The windy bays in the north are also becoming popular spots for kitesurfing and windsurfing. While organized recreational facilities can be limited outside of major tourist hubs, the natural playground that Madagascar offers is truly vast and unforgettable.

32. Environmental Concerns

Madagascar is facing an environmental crisis of staggering proportions, a situation that threatens its globally unique biodiversity and the livelihoods of its people. The single most critical environmental concern is deforestation. Since the arrival of humans, it is estimated that Madagascar has lost over 90% of its original forest cover. This destruction is driven by a complex mix of factors, all linked to poverty and population growth. The primary cause is a traditional agricultural practice known as “tavy” (slash-and-burn agriculture), where forests are cleared and burned to create temporary agricultural plots, primarily for rice cultivation. As the soil loses its fertility after a few seasons, farmers move on to clear a new patch of forest. This practice, combined with illegal logging of precious hardwoods like rosewood and ebony, the production of charcoal for cooking fuel, and the clearing of land for cattle grazing, has led to a catastrophic loss of habitat for the island’s unique wildlife.

The consequences of this rampant deforestation are severe and far-reaching. The loss of forest habitat is the primary driver of the island’s biodiversity crisis, pushing thousands of endemic species, including many species of lemur, to the brink of extinction. It also has devastating impacts on the land itself. Without the trees to hold the soil in place, massive soil erosion occurs. During the rainy season, tons of red laterite soil are washed into the rivers, a process so extensive that astronauts have described Madagascar as “bleeding” into the ocean. This erosion silts up rivers and irrigation canals, reduces agricultural productivity, and degrades freshwater ecosystems. It also damages vital marine habitats like coral reefs as the sediment smothers them. This cycle of deforestation and erosion creates a vicious feedback loop, further impoverishing rural communities and increasing their reliance on unsustainable land-use practices.

Climate change is an additional and exacerbating threat to Madagascar’s already fragile environment. The country is highly vulnerable to extreme weather events. The eastern coast is regularly hit by powerful cyclones that cause widespread damage and loss of life. In contrast, the southern part of the country has been experiencing a prolonged and severe drought, which scientists have linked to climate change. This has led to a catastrophic famine, pushing millions of people into acute food insecurity. Addressing these immense environmental challenges requires a multifaceted approach. Numerous international and local conservation organizations are working on the ground to protect remaining forests, promote reforestation with native species, and introduce sustainable agricultural alternatives to “tavy.” However, these efforts are continuously challenged by the country’s deep-seated poverty and political instability. For Madagascar, finding a sustainable balance between the needs of its people and the preservation of its unparalleled natural heritage is the most critical challenge of the 21st century.

33. Marriage & Courtship

In Madagascar, the customs surrounding courtship and marriage are a fascinating blend of tradition, family obligation, and modern influences. While dating in urban centers like Antananarivo may resemble Western practices, in most of the country, courtship is a family affair. The journey towards marriage traditionally begins not with the couple, but with their families. When a man wishes to marry a woman, his family will formally approach her family to declare his intentions. This process, known as “fisehoana” or “ala-volana,” involves intricate, formal speeches full of proverbs and symbolic language, delivered by representatives from both families. It is a negotiation and a demonstration of respect, where the groom’s family must prove his worthiness and ability to care for the bride. The “vody ondry,” or bride price, is a central part of this negotiation. It is not seen as buying the bride, but rather as a symbolic gift to her family to compensate them for the loss of their daughter and to honor them for having raised her well. This gift often consists of money, zebu cattle, and other goods.

The wedding celebration itself is a joyous and communal event, often lasting for several days. It is legally required for couples to have a civil ceremony at the local town hall (mairie). This is often followed by a religious ceremony, as Christianity is widespread. The celebration culminates in a huge feast, where the entire community is invited to share in the couple’s happiness. Food, particularly rice and zebu meat, plays a central role, symbolizing prosperity and abundance. Throughout the celebration, traditions reinforcing the importance of family and community are paramount. The couple receives blessings and advice (tsodrano) from the elders, and the event serves to formally unite not just two individuals, but two entire families. These traditions, from the formal speeches to the bride price, underscore the Malagasy philosophical belief that an individual is inseparable from their lineage and community, and that marriage is a sacred bond that strengthens these vital social ties.

34. Work Opportunities

For foreigners seeking work opportunities in Madagascar, the landscape is one of specific niches and significant challenges, requiring a combination of specialized skills, cultural adaptability, and a resilient spirit. The job market for expatriates is not large and is concentrated in a few key sectors. One of the most prominent areas for foreign employment is in the conservation and development sector. Given the country’s unique biodiversity and its severe environmental and social challenges, a large number of international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and multilateral agencies like the UN and the World Bank operate in Madagascar. These organizations frequently hire international experts for roles in project management, scientific research, conservation, public health, and sustainable development. These positions often require advanced degrees, previous field experience, and proficiency in French, the country’s main administrative language. These roles offer a unique chance to contribute to meaningful work but are often based in remote and challenging locations.

Another sector with opportunities for foreign nationals is in mining and natural resources. Madagascar has significant deposits of minerals like nickel, cobalt, and ilmenite, and large-scale extraction projects are typically run by international companies. These companies often hire expatriate managers, engineers, geologists, and other technical specialists with skills that are not readily available in the local workforce. Similarly, the tourism and hospitality industry, particularly in the high-end segment, can offer opportunities for experienced foreign managers, chefs, or specialized guides (e.g., dive instructors). Some foreigners also find success through entrepreneurship, starting their own businesses that cater to the tourism industry, such as lodges, restaurants, or tour operations, especially in popular areas like Nosy Be. However, navigating the bureaucracy of starting a business can be a complex and lengthy process.

Securing legal employment in Madagascar requires navigating a formal and often slow bureaucratic process. A foreigner must obtain a work permit (autorisation d’emploi) and a long-stay visa that can be converted into a residence permit. This process almost always requires a formal contract from an employer in Madagascar, who must justify the need to hire a foreign national over a Malagasy citizen. The vast majority of jobs are, quite rightly, reserved for the local population. It is extremely difficult to find work upon arrival. The most effective approach is to secure a position from abroad through organizations that specialize in international recruitment. Fluency in French is a near-universal requirement for any professional role. While the opportunities are limited and the challenges are real, for those with the right skills and a passion for this unique country, working in Madagascar can be an incredibly profound and life-changing experience.

35. Education

The education system in Madagascar is modeled on the French system and has faced enormous challenges in providing quality schooling to its young and rapidly growing population. The system is structured into several levels: preschool, a five-year primary cycle, a four-year lower secondary cycle, and a three-year upper secondary cycle. Education is theoretically compulsory from the ages of 6 to 16. The language of instruction has been a subject of ongoing debate and policy changes, shifting between French and Malagasy. Currently, the official policy promotes bilingual education, but in practice, the quality of instruction in either language can be poor, and a lack of textbooks and qualified teachers is a major handicap. While primary school enrollment rates are relatively high, the system suffers from very high dropout rates. Many children, particularly in impoverished rural areas, leave school early to help their families with agricultural work or because their parents cannot afford the associated costs, such as for school supplies, even though tuition is technically free in public schools. This creates a cycle of poverty and limits opportunities for social mobility.

Access to and quality of education vary dramatically between urban and rural areas and between public and private institutions. In the capital, Antananarivo, and other major cities, there is a network of private schools, many of which are religiously affiliated or follow a French curriculum. These schools offer a much higher standard of education but are only accessible to the small, affluent elite who can afford the high fees. In contrast, public schools, especially in remote rural areas, are often severely under-resourced. It is not uncommon for schools to lack basic facilities like desks, electricity, or clean water. Teachers are often poorly paid and may have to handle large, multi-grade classes. The disparity in educational outcomes between rich and poor, and urban and rural students, is immense and is one of the most significant challenges to the country’s long-term development.

Higher education is centered around the country’s six public universities, one in each of the former provinces, with the University of Antananarivo being the oldest and largest. There are also a number of private and technical colleges. However, the university system is also plagued by underfunding, overcrowding, and periodic student strikes, which can disrupt the academic year. The quality of higher education has declined over the years, and it struggles to produce enough graduates with the skills needed by the modern economy. Many of the country’s brightest students seek opportunities to study abroad, often in France, and many do not return, contributing to a significant “brain drain.” Numerous international organizations and NGOs are working to support the education sector in Madagascar through teacher training programs, school construction, and providing educational materials, but the scale of the challenge remains vast.

36. Communication & Connectivity

Communication and connectivity in Madagascar present a picture of significant contrasts, with rapidly growing mobile networks in urban centers set against a vast rural landscape where access remains a major challenge. For most travelers, staying connected is easiest through the mobile phone network. The country has three main mobile operators: Telma, Orange, and Airtel. In the capital, Antananarivo, and other major towns and along the main national routes, 3G and 4G coverage is generally available and reliable. This allows for internet access, social media use, and navigation via smartphone. However, once you venture off the beaten path and into more remote rural areas, mobile signal can become patchy or completely non-existent. For any visitor planning a trip, purchasing a local prepaid SIM card upon arrival at the airport in Antananarivo is the most practical and cost-effective option. SIM cards and top-up vouchers are cheap and readily available, providing much better value for calls and data than international roaming.

Internet access in Madagascar is still a developing service. While the country is connected to undersea fiber-optic cables, the “last mile” infrastructure to bring high-speed internet to homes and businesses is limited. In Antananarivo, you can find internet cafes, and most mid-range to high-end hotels and restaurants will offer Wi-Fi to their guests. However, the speed and reliability of these connections can vary dramatically and may not be suitable for high-bandwidth activities like video streaming or large file downloads. In most smaller towns and rural areas, Wi-Fi is a rarity. Travelers who need to stay connected, particularly for work, should rely on the mobile data from their local SIM card and be prepared for periods of being offline, especially when traveling through the country’s spectacular but remote national parks and reserves. This digital divide is a major hurdle for the country’s development, limiting access to information and opportunities for the majority of the population who live in rural areas.

Traditional forms of communication are still relevant, although becoming less so. The national postal service, Paositra Malagasy, can be used for sending postcards, but international mail services can be slow and unreliable. Public payphones are virtually non-existent. When making calls, the country code for Madagascar is +261. It’s important to be aware that the power grid can also be unreliable, with frequent power cuts (known as “delestage”) even in the capital. This can affect your ability to charge devices and can also disrupt internet and mobile network services. For this reason, carrying a portable power bank is a highly recommended accessory for any traveler in Madagascar. Ultimately, while connectivity is improving, visitors should embrace the opportunity to disconnect and immerse themselves in the incredible natural and cultural experiences that the country offers, rather than expecting the constant connectivity available in more developed nations.

37. National Symbols

The national symbols of Madagascar are a vibrant reflection of the island’s unique cultural fusion, its proud history, and its extraordinary natural heritage. The most prominent state symbol is the national flag, adopted in 1958. It consists of three colors: a vertical white stripe on the hoist side, with horizontal stripes of red and green on the fly side. The white and red are the colors of the historic Merina Kingdom, which unified much of the island in the 19th century, and they also symbolize the Southeast Asian origins of many Malagasy people. The green represents the Hova, the traditional commoner class, and the lush coastal regions, symbolizing hope and the country’s agricultural wealth. Together, the colors represent the themes of purity, sovereignty, and patriotism. The national anthem, “Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô!” (“Oh, Our Beloved Ancestors’ Land!”), further reinforces the deep cultural importance of the ancestors and the homeland.

The national seal of Madagascar features a map of the island on a white disc, with the head of a zebu cattle, a hugely important animal in Malagasy culture, superimposed on it. The zebu represents wealth and is central to many cultural rituals, from sacrifices to dowries. Below the zebu head are green rice paddies, symbolizing the nation’s staple food, and at the top is the Traveller’s Palm, a plant native to Madagascar that is itself a powerful cultural symbol. The motto of the republic, “Tanindrazana, Fahafahana, Fandrosoana” (Fatherland, Freedom, Progress), is inscribed on the seal. The Traveller’s Palm (Ravinala madagascariensis) is often considered the national plant. It is not a true palm but is a member of the Strelitziaceae family. Its distinctive fan-like shape is a common sight, and it earned its name because the sheaths of its stems hold water, which could be used as an emergency source of drinking water for travelers.

Madagascar’s most famous symbols are undoubtedly its unique flora and fauna, which are a source of immense national pride and the primary draw for international visitors. While there is no single officially designated national animal, the Ring-tailed Lemur (Lemur catta), with its distinctive black and white striped tail, is the most iconic and recognizable of all the lemur species and serves as an unofficial animal ambassador for the country. Similarly, the majestic Baobab trees, particularly the six endemic species found on the island, are a powerful symbol of Madagascar’s otherworldly landscapes. The Avenue of the Baobabs is a protected natural monument and one of the most photographed sights in the nation. This extraordinary biodiversity, from the smallest chameleon to the largest lemur, is the ultimate symbol of Madagascar’s status as a precious and irreplaceable “eighth continent.”

| National & Cultural Symbols of Madagascar | |

|---|---|

| National Flag | White, Red, and Green Tricolour |

| National Anthem | “Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô!” (Oh, Our Beloved Ancestors’ Land!) |

| National Motto | “Tanindrazana, Fahafahana, Fandrosoana” (Fatherland, Freedom, Progress) |

| Symbolic Animal | Zebu (Bos taurus indicus) |

| Unofficial National Plant | Traveller’s Palm (Ravinala madagascariensis) |

| Unofficial National Animal | Ring-tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) |

| Notable Flora | Notable Fauna |

|---|---|

| Baobab Trees (6 endemic species), Traveller’s Palm, Spiny Forest Plants (Didiereaceae), Orchids (over 800 species), Pitcher Plants, Pachypodium | Lemurs (over 100 species, all endemic), Chameleons (half of world’s species), Fossa, Tenrecs, Geckos, Radiated Tortoise, Tomato Frog |

38. Tourism

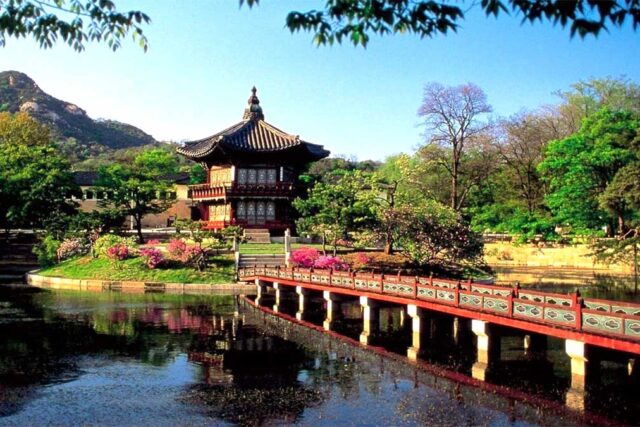

Tourism in Madagascar is an adventure into a world apart, offering an unparalleled experience for nature lovers, wildlife enthusiasts, and intrepid travelers. The country’s main draw is its utterly unique biodiversity, which has evolved in isolation for millions of years. Often called the “eighth continent,” Madagascar is home to thousands of species of plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth. The undisputed stars of the show are the lemurs, a primate group endemic to the island. Visitors can see dozens of species, from the iconic ring-tailed lemurs in the south to the singing Indri, the largest living lemur, in the eastern rainforests. National parks and reserves are the cornerstones of the tourism industry, protecting these precious habitats and providing the infrastructure for visitors to experience them. Key destinations include Andasibe-Mantadia National Park for rainforest wildlife, Isalo National Park for its spectacular sandstone canyons and natural swimming pools, and Ranomafana National Park for its dense cloud forest and rich biodiversity.

Beyond the wildlife, Madagascar’s landscapes are breathtakingly diverse and offer a huge range of experiences. The iconic Avenue of the Baobabs near Morondava is a must-see, offering one of the most magical and photogenic landscapes on the planet, especially at sunrise and sunset. In the north, the Ankarana Reserve features dramatic “tsingy,” which are karst limestone pinnacles forming a veritable stone forest that can be explored via suspension bridges and trails. For coastal and marine experiences, the archipelago around Nosy Be in the northwest is the country’s premier beach destination, offering beautiful sandy beaches, turquoise waters, opportunities for scuba diving and snorkeling on coral reefs, and whale watching in season. The island of Île Sainte-Marie off the east coast is another popular spot, known for its laid-back atmosphere and as a major breeding ground for humpback whales. This incredible variety, from rainforest to desert and from mountains to coral reefs, makes Madagascar a truly unique travel destination.

39. Visa and Entry Requirements

Understanding the visa and entry requirements for Madagascar is a crucial step for any traveler planning a trip to this unique island nation. Unlike many countries that offer visa-free access to certain nationalities, almost all foreign visitors to Madagascar are required to obtain a visa. However, the country has a straightforward and well-established visa-on-arrival system, which makes the process relatively simple for tourists. This means that for stays of up to 90 days, travelers from most countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and all EU member states, can purchase their tourist visa upon arrival at the main international airport, Ivato (TNR), in Antananarivo, as well as at other international airports like Nosy Be. This convenience makes spontaneous or short-notice trips much more feasible than in countries that require lengthy pre-application processes.

To obtain the visa on arrival, travelers must present a passport that is valid for at least six months from the date of entry and has at least one blank page for the visa sticker and entry stamps. The fees for the tourist visa are payable in cash, and it is highly recommended to have the exact amount in a major currency like Euros or US Dollars, although Malagasy Ariary is also accepted. The fee structure typically depends on the duration of the intended stay, with options for 30-day, 60-day, or 90-day visas. In addition to a valid passport and the visa fee, immigration officials may also ask for proof of a return or onward flight ticket and sometimes proof of accommodation. It is always wise to have these documents printed and easily accessible upon arrival to ensure a smooth process. While the visa-on-arrival system is efficient, travelers can also opt to apply for an “e-visa” online in advance through the official government portal, which can sometimes speed up the process at the airport.

For those planning to stay longer than 90 days, or for non-tourist purposes such as work, volunteering, or research, a different type of visa is required. This “transformable” visa must be applied for at a Malagasy embassy or consulate in your country of residence before you travel. Upon arrival in Madagascar, this visa allows you to apply for a long-term residence permit (Carte de Résident). This process is significantly more complex and bureaucratic, requiring a range of documents and several visits to government offices in Antananarivo. Therefore, it is essential for anyone planning a long-term stay to start this process well in advance. It is also highly recommended that all travelers check the very latest visa regulations and health requirements (such as for Yellow Fever, if arriving from an infected area) with their nearest Malagasy embassy before finalizing their travel plans, as rules and fees can change.

40. Useful Resources

To ensure a safe and well-organized trip to Madagascar, it is highly recommended to consult official government sources and reputable travel organizations. These resources provide the most current information on visa requirements, safety and security, health advisories, and conservation efforts, which are all critical for planning a successful adventure in this unique country.

- Madagascar National Tourism Board: The official source for tourism information, providing details on destinations, national parks, and cultural highlights. The website is an excellent starting point for travel planning. Visit www.madagascar-tourisme.com/en/.

- Madagascar National Parks: This is the official website for the network of national parks and reserves in Madagascar. It provides essential visitor information, including park locations, activities, and the importance of conservation. Find it at www.parcs-madagascar.com.

- U.S. Department of State – Madagascar Travel Advisory: Offers detailed and regularly updated information for U.S. citizens on safety, security, local laws, health, and entry requirements. This is a crucial resource for understanding potential risks. Access it at travel.state.gov.

- UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) – Madagascar Travel Advice: Provides comprehensive travel advice for British nationals, covering safety, health, visa rules, and areas to which the FCDO advises against travel. Find it at gov.uk.

- E-visa System for Madagascar: The official government portal for applying for an electronic visa in advance of your trip. This can help streamline the arrivals process. The official site is www.evisamada.gov.mg/en/.

One Comment

https://t.me/Top_BestCasino/128