Tibet Travel Guide

Table of Contents

- 21) Brief History

- 22) Geography

- 23) Politics and Government

- 24) Law and Criminal Justice

- 25) Foreign Relations

- 26) Administrative Divisions

- 27) Economy & Commodities

- 28) Science and Technology

- 29) Philosophy

- 30) Cultural Etiquette

- 31) Sports and Recreation

- 32) Environmental Concerns

- 33) Marriage & Courtship

- 34) Work Opportunities

- 35) Education

- 36) Communication & Connectivity

- 37) National Symbols

- 38) Tourism

- 39) Visa and Entry Requirements

- 40) Useful Resources

21) Brief History

The history of Tibet is a rich and complex saga, a story of empires, profound spirituality, and a unique cultural identity forged in the isolation of the world’s highest plateau. The origins of the Tibetan people are woven into myth and ancient history, but the story of a unified Tibet begins in the 7th century with the visionary leader Songtsen Gampo. He is credited with uniting the disparate tribes of the Yarlung Valley and founding the Tibetan Empire, which would become a formidable power in Central Asia for over two centuries. His reign was a period of immense cultural and political transformation. He established Lhasa as his capital, built the first structures of what would become the Potala Palace, and, through his marriages to Princess Wencheng of China and Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal, he introduced Buddhism to the Tibetan court. This introduction of Buddhism was the single most important event in Tibetan history, as the religion would come to permeate every aspect of Tibetan life, from art and politics to medicine and personal identity, shaping the very soul of the nation.

The Tibetan Empire, at its height, rivaled the Tang Dynasty in China and the Arab Caliphates, with its influence stretching across Central Asia. However, internal conflicts and a struggle between the new Buddhist faith and the indigenous Bön religion led to its fragmentation in the 9th century. This began a period of decentralization, but it was also a time when Buddhism took deep root among the populace, leading to the establishment of major monastic orders like the Nyingma, Kagyu, and Sakya schools. A pivotal development occurred in the 13th century when Tibet established a unique “priest-patron” relationship with the Mongol Empire under Kublai Khan. The Mongol rulers granted the head of the Sakya school temporal authority over Tibet, beginning a long tradition of rule by religious hierarchs. This system evolved, and by the 17th century, the Gelug school, led by the charismatic 5th Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso, unified Tibet once again. With the backing of his Mongol patron, Güshi Khan, he established a theocratic government in Lhasa, consolidated the power of the Dalai Lamas as both the spiritual and temporal rulers of Tibet, and began the construction of the magnificent Potala Palace as we know it today.

This unique system of governance, with the Dalai Lama at its head, continued for centuries, maintaining Tibet’s distinct identity and relative isolation. The 20th century, however, brought profound and traumatic change. Following the Chinese Revolution, the newly established People’s Republic of China asserted its claim over Tibet, which it viewed as a historical part of its territory. In 1950, the People’s Liberation Army entered Tibet, and in 1951, the Seventeen Point Agreement was signed, formalizing Chinese sovereignty but promising to maintain the existing political system and religious freedom. Tensions between the Tibetan government and the Chinese authorities escalated, culminating in the Tibetan Uprising of 1959. The uprising was suppressed, leading to the flight of the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, and thousands of his followers into exile in India. Since then, the Tibet Autonomous Region has been under the direct administration of the Chinese central government. This recent history is a source of ongoing political contention, with the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan Government in Exile advocating for autonomy, while the Chinese government emphasizes the economic development and modernization it has brought to the region.

22) Geography

The geography of Tibet is defined by its staggering scale and sublime, raw beauty, earning it the evocative title “The Roof of the World.” Situated in the heart of Asia, the Tibetan Plateau is the highest and largest plateau on Earth, with an average elevation exceeding 4,500 meters (14,800 feet). This immense, elevated landmass is the source of many of Asia’s most vital rivers, including the Indus, Brahmaputra (known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet), Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers, making it the “Water Tower of Asia” and critically important to the downstream nations that depend on these water resources. The plateau is encircled by colossal mountain ranges that seal it off from the rest of the continent. To the south and west lies the formidable arc of the Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range, which includes Mount Everest, known as Chomolungma in Tibetan, straddling the border with Nepal. To the north, the Kunlun Mountains create a barrier with the Tarim Basin, and to the east, the rugged Hengduan Mountains separate the plateau from the lowlands of central China.

This extreme altitude and mountainous terrain create a unique and harsh environment. The climate is predominantly alpine, characterized by strong sunlight, thin, dry air, and a vast diurnal temperature range, where a warm, sunny day can quickly give way to a freezing night. Winters are long and intensely cold, while summers are short and cool. The Himalayan range acts as a massive barrier to the Indian monsoon, resulting in a rain shadow effect that makes most of the plateau, particularly the northern Changtang region, an arid, high-altitude desert. Precipitation is scarce and falls mainly in the summer months, with the southeastern parts of Tibet receiving significantly more moisture, allowing for the growth of forests in the lower river valleys. The landscape is a breathtaking panorama of vast, rolling plains, crystal-clear turquoise lakes, and snow-capped peaks that seem to touch the sky. The sheer scale and emptiness of the landscape can evoke a profound sense of awe and solitude.

Tibet’s geography can be broadly divided into three main regions. The northern plateau, or Changtang, is a vast, high-altitude steppe and wilderness, dotted with large salt lakes and inhabited by nomadic pastoralists and a unique array of wildlife adapted to the harsh conditions, such as the wild yak, Tibetan antelope (chiru), and Tibetan wild ass (kiang). The southern and central region is characterized by the great river valleys, including the Yarlung Tsangpo Valley, which is the cradle of Tibetan civilization. This is the most agriculturally productive area, where barley is the staple crop, and it is where most of Tibet’s major cities and monasteries, including Lhasa, Shigatse, and Gyantse, are located. Finally, the eastern region, part of the traditional Tibetan area of Kham, is a land of deep gorges and forested mountains, with a climate and topography that are more varied than the central plateau. This dramatic and challenging geography has not only shaped the unique Tibetan culture but also plays a crucial role in the regional and global climate system.

23) Politics and Government

The political structure and governance of Tibet are complex and highly contentious subjects, with two competing narratives and systems existing in parallel. Officially and internally, the region is governed as the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), an integral part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This system was established following the events of 1959. The governance of the TAR is structured in line with the political system of the PRC, which is a single-party state led by the Communist Party of China (CPC). The highest government body within the region is the Regional People’s Government, which is led by a Chairman. However, the true locus of power lies with the Regional Committee of the Communist Party of China and its Party Secretary. By tradition and policy, the Chairman of the government is typically an ethnic Tibetan, while the Party Secretary, who holds the ultimate authority, has always been a Han Chinese appointed by the central leadership in Beijing. This structure ensures that the region is tightly controlled by and integrated into the national political system of the PRC.

The government of the TAR emphasizes its role in bringing economic development, modernization, and social stability to a region it considers to have been a feudal theocracy before 1951. Beijing’s policies focus heavily on infrastructure development, such as the construction of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway and an extensive network of airports and highways, which are aimed at integrating Tibet’s economy with the rest of China and improving living standards. The central government also invests heavily in poverty alleviation programs, healthcare, and education within the TAR. The political system is administered through a hierarchy of prefectures, counties, and townships. All key decisions on economic policy, security, and social programs are directed by the central government in Beijing, consistent with China’s unitary state model. While the TAR is designated as an “autonomous region,” the scope of this autonomy is limited and does not extend to fundamental political or religious matters, which remain under the firm control of the central party-state apparatus.

In stark contrast to this internal system is the Tibetan Government in Exile, officially known as the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), which is based in Dharamshala, India. This government was established by the 14th Dalai Lama after he fled Tibet in 1959. For decades, the CTA was led by the Dalai Lama as the head of state, continuing the tradition of theocratic rule. However, in a major political reform in 2011, the Dalai Lama devolved his political authority to a democratically elected leader. The head of the CTA is now the Sikyong (formerly Kalön Tripa, or Prime Minister), who is elected by the Tibetan diaspora community around the world. The CTA also has an elected Parliament-in-Exile. The primary political goal of the CTA, as articulated in the Dalai Lama’s “Middle Way Approach,” is not to seek full independence for Tibet but to achieve genuine autonomy for all Tibetan people within the framework of the PRC. This would grant Tibetans control over their own cultural, religious, and educational affairs. This position, however, is not accepted by the Chinese government, and there have been no formal dialogues between the two sides for over a decade. This duality of governance—one official and state-controlled, the other in exile and advocating for autonomy—defines the contemporary political reality of Tibet.

24) Law and Criminal Justice

The legal and criminal justice system operating within the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) is a direct extension of the legal framework of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As an administrative division of China, the TAR does not have a separate or autonomous legal system. The laws that are applicable throughout mainland China, including the Criminal Law, the Criminal Procedure Law, and various civil and administrative laws, are all in full force in Tibet. The Chinese legal system is fundamentally a civil law system, with its roots in socialist legal theory, and is characterized by the dominant role of the state and the Communist Party. The principle of “socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics” emphasizes the leadership of the Communist Party over the legal system, meaning that the judiciary is not independent in the Western sense of the term. All courts and law enforcement agencies ultimately answer to the political leadership of the party.

The administration of justice in the TAR follows the standard Chinese structure. The court system is hierarchical, consisting of Basic People’s Courts at the county level, Intermediate People’s Courts at the prefectural level, the High People’s Court of the Tibet Autonomous Region, and at the apex, the Supreme People’s Court in Beijing. Law enforcement is carried out by the Public Security Bureau (PSB), the national police force, which is responsible for police work, investigations, and state security. The procuratorate is responsible for approving arrests and prosecuting cases in court. A key aspect of the criminal justice system in China, and therefore in the TAR, is the emphasis on maintaining social stability and state security. This is particularly pronounced in Tibet, where authorities are highly sensitive to any activities perceived as “separatist” or threatening to national unity. The legal framework includes broadly defined laws against “endangering state security,” which have been used to prosecute individuals for expressing dissent or showing allegiance to the Dalai Lama.

For foreign travelers, it is crucial to understand that they are subject to all Chinese laws while in the Tibet Autonomous Region. The legal protections and procedures can differ significantly from those in their home countries. For example, the right to legal counsel, the presumption of innocence, and the right to a speedy trial may not be implemented in the same way. The PSB has broad authority to detain and question individuals. Any political activities, such as protesting, distributing flags or photos of the Dalai Lama, or engaging in pro-independence discussions, are strictly illegal and can lead to severe consequences, including detention and deportation. Visitors are expected to adhere strictly to the terms of their travel permits, follow the itinerary arranged by their tour operator, and refrain from any activities that could be construed as political or religious activism. Adherence to these rules is essential for a safe and trouble-free visit to the region.

25) Foreign Relations

The concept of “foreign relations” for Tibet is uniquely complex and operates on two distinct and conflicting levels. Officially, as the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) is an integral part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), its foreign relations are exclusively handled by the central government in Beijing. The TAR, as a provincial-level entity, does not have the authority to conduct its own independent diplomacy, establish embassies, or sign international treaties. All interactions with other countries, international organizations like the United Nations, and foreign leaders are managed by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign affairs. From Beijing’s perspective, any issue related to Tibet is considered a purely internal affair of China. The Chinese government actively opposes any form of official contact between foreign governments and the Tibetan Government in Exile or the Dalai Lama, viewing such meetings as interference in its domestic affairs and a challenge to its sovereignty over the region. Beijing uses its significant diplomatic and economic influence to promote its narrative on Tibet, emphasizing the economic progress and social development in the region since 1951.

The Chinese government does engage in what it terms “cultural exchanges” and “people-to-people” diplomacy concerning Tibet. It organizes government-sponsored tours for foreign diplomats, journalists, and academics to visit the TAR, showcasing infrastructure projects, poverty alleviation efforts, and state-supported cultural preservation initiatives. These tours are tightly controlled and aim to present a positive image of Chinese governance in the region. Furthermore, China actively engages with international bodies to counter criticism of its policies in Tibet, presenting its actions as necessary measures to ensure national security, combat separatism, and improve the livelihoods of the Tibetan people. It points to the significant financial investment it has made in the region as evidence of its commitment to Tibet’s well-being. This state-directed engagement is the only form of “foreign relations” that is officially sanctioned and conducted from within Tibet itself.

In parallel, the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), or the Tibetan Government in Exile, based in Dharamshala, India, conducts its own form of international relations. While no country in the world formally recognizes the CTA as a sovereign government, it maintains a global network of “Offices of Tibet” in cities like New York, London, Brussels, and Tokyo, which function as de facto embassies. The primary goal of the CTA’s foreign policy is to advocate for the “Middle Way Approach,” which seeks genuine autonomy for Tibet within China, and to bring international attention to the human rights situation and the preservation of Tibetan culture and religion. The most powerful asset in this diplomatic effort is the global stature of the 14th Dalai Lama. As a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and a widely respected spiritual leader, his meetings with world leaders, politicians, and celebrities consistently keep the issue of Tibet on the international agenda. This creates a persistent diplomatic challenge for Beijing and ensures that the Tibetan perspective, as articulated by the exile community, continues to have a voice and significant influence in the international community, even without formal diplomatic recognition.

26) Administrative Divisions

The administrative divisions of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) are structured according to the hierarchical system used throughout the People’s Republic of China. As a provincial-level autonomous region, the TAR is divided into several prefectures, which are then further subdivided into counties, districts, and townships. This structure is the framework through which the policies of the central government in Beijing are implemented at the local level across the vast expanse of the Tibetan plateau. The TAR is currently organized into seven prefecture-level divisions. These consist of six prefecture-level cities and one prefecture. A “prefecture-level city” in the Chinese system is an administrative unit that typically comprises an urban core (the city proper) as well as a large surrounding rural area, including many counties. This system ensures that urban centers provide administrative oversight for their rural hinterlands.

The capital of the TAR, Lhasa, is one of these prefecture-level cities. It is the political, economic, and cultural heart of the region and is administered as a single entity that includes not only the main urban center but also several surrounding counties. The other five prefecture-level cities are Shigatse, the second-largest city and the traditional seat of the Panchen Lama; Chamdo, a major center in the historical Kham region in the east; Nyingchi (or Linzhi), located in the lower-altitude, forested region of southeastern Tibet; Shannan (or Lhoka), located in the Yarlung Tsangpo Valley and considered the cradle of Tibetan civilization; and Nagqu, which administers a vast area of the northern Changtang plateau. The one remaining prefecture-level division is Ngari Prefecture, a remote, high-altitude, and sparsely populated region in the far west of Tibet, which is home to sacred sites like Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar.

Each of these prefecture-level divisions is further subdivided into county-level divisions. As of the early 2020s, the TAR is composed of 74 county-level divisions. These include districts, which are subdivisions of the urban core of the prefecture-level cities, and counties, which cover the more rural areas. The counties are the fundamental unit of local government, responsible for the direct administration of towns, townships, and villages. This administrative structure, from the regional government in Lhasa down to the local townships, provides the mechanism for delivering social services like education and healthcare, managing local infrastructure, and enforcing the laws and regulations of the state. It is a system designed for central control, ensuring that policies formulated in Beijing are consistently applied across all levels of governance within the Tibet Autonomous Region.

27) Economy & Commodities

The economy of Tibet has undergone a dramatic and fundamental transformation over the past several decades, moving from a traditional, subsistence-based agricultural and pastoral model to an economy heavily subsidized and directed by the Chinese central government. Historically, the Tibetan economy was characterized by self-sufficiency, with the vast majority of the population engaged in farming in the river valleys or nomadic herding on the high plateau. The staple crop was highland barley, used to make *tsampa* (roasted barley flour), and herders raised yaks, sheep, and goats, which provided meat, dairy products, wool, and transportation. Trade was limited, mostly involving the exchange of salt, wool, and medicinal herbs for tea, grain, and manufactured goods from China and India. This traditional economy was largely non-monetized and deeply intertwined with the monastic system, which was a major landholder and economic actor.

Since its incorporation into the People’s Republic of China, and particularly in recent decades, Tibet’s economy has been reshaped by massive state-led investment. The central government in Beijing provides a huge portion of the TAR’s budget through direct subsidies, which fund infrastructure, social services, and government operations. This has resulted in rapid GDP growth and significant improvements in material living standards for many. A key pillar of this new economy is infrastructure development. The construction of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, which connected Lhasa to the rest of China’s rail network in 2006, along with an expanding network of highways and airports, has been a game-changer, breaking the region’s historical isolation and facilitating the movement of goods, people, and resources. This has spurred growth in construction, transport, and logistics, which are now major components of the regional economy.

The modern Tibetan economy is increasingly dominated by the tertiary (services) sector, with tourism being a designated pillar industry. The government has invested heavily in developing tourism infrastructure to attract domestic and international visitors to the region’s spectacular landscapes and unique cultural sites. However, this industry is tightly controlled and subject to political sensitivities. Another major economic driver is government and public sector employment. In terms of commodities, Tibet possesses significant mineral resources, including copper, gold, lithium, and chromium, and mining has become an expanding industry, though it remains a sensitive issue due to environmental concerns. The traditional agricultural and pastoral sectors still employ a large portion of the rural population, but the government is actively promoting programs to modernize these practices and settle nomadic communities. This state-driven economic model has brought modernization and development but has also created a high degree of economic dependence on the central government.

28) Science and Technology

The intersection of science and technology with the unique environment of Tibet presents a fascinating picture of both ancient knowledge and modern innovation. For centuries, Tibet developed its own sophisticated systems of science, which were deeply integrated with its Buddhist philosophy and worldview. The most prominent of these is Traditional Tibetan Medicine (*Sowa-Rigpa*), a holistic system of healing that is one of the oldest continuously practiced medical traditions in the world. It combines a complex understanding of anatomy and physiology with principles of pharmacology, using thousands of plants, minerals, and animal products found on the high plateau. This system also incorporates diagnostic techniques like pulse analysis and urinalysis, and treatments that include diet, behavior modification, and complex herbal formulas. Traditional Tibetan astronomy and astrology were also highly developed, used for creating the lunar calendar, which is essential for determining the timing of religious festivals, and for making astrological predictions.

In the modern era, the high-altitude environment of the Tibetan Plateau has made it a crucial natural laboratory for contemporary scientific research, particularly in the fields of geology, glaciology, and climate science. The plateau is often referred to as the “Third Pole” because its ice fields contain the largest reserve of fresh water outside of the polar regions. Scientists from China and around the world study the retreat of Tibetan glaciers as a key indicator of global climate change. Understanding the dynamics of the plateau’s atmosphere and its role in influencing the Asian monsoon is another critical area of research. The unique geology of the plateau, formed by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates, provides invaluable insights into plate tectonics and mountain formation. China has established numerous research stations across the plateau to monitor these environmental systems, viewing this research as vital for understanding regional and global climate patterns.

The Chinese government has also made significant investments in bringing modern technology and infrastructure to the Tibet Autonomous Region. The construction of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway is a marvel of modern engineering, requiring innovative solutions to build a stable railway on permafrost at extreme altitudes. The country has also been expanding its telecommunications network, bringing mobile phone service and internet connectivity to many remote parts of the plateau, which has had a profound impact on communication and access to information. In the field of energy, there is a strong focus on developing renewable resources. Tibet has immense potential for solar power due to its high altitude and clear skies, and numerous large-scale solar farms have been built. Hydropower is also being developed on the region’s powerful rivers. This infusion of modern science and technology is rapidly changing the landscape and the way of life in Tibet, presenting both opportunities for development and challenges for the preservation of its traditional culture and fragile environment.

29) Philosophy

Tibetan philosophy is one of the most profound, complex, and systematic intellectual traditions in the world, and it is inextricably linked to the development of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. It is not merely an academic discipline but a living practice aimed at the fundamental transformation of the mind and the ultimate goal of achieving enlightenment, or Buddhahood, for the benefit of all sentient beings. The philosophical landscape of Tibet is built upon the vast body of texts translated from Sanskrit during the “first dissemination” of Buddhism in the 7th-9th centuries and the “second dissemination” from the late 10th century onwards. These include the *Kangyur*, the translated words of the Buddha, and the *Tengyur*, the translated commentaries by great Indian masters like Nagarjuna, Asanga, and Dharmakirti. Tibetan scholars and yogis did not simply preserve this knowledge; they expanded upon it, creating their own vast and sophisticated body of philosophical literature and debate.

At the heart of Tibetan Buddhist philosophy are the core concepts of emptiness (*shunyata*), compassion (*karuna*), and the nature of consciousness. The Madhyamaka, or “Middle Way,” school, founded by Nagarjuna, is central to all Tibetan traditions. It uses rigorous logical analysis to deconstruct our conventional understanding of reality, arguing that all phenomena, including the self, are “empty” of any inherent, independent existence. They are seen as being interdependently originated, arising in reliance upon other factors. Understanding this emptiness is believed to be the key to cutting the root of suffering, which arises from our attachment to things we mistakenly believe are solid and permanent. This profound philosophical insight into emptiness is always paired with the cultivation of *bodhicitta*, the compassionate aspiration to attain enlightenment in order to be able to liberate all other beings from suffering. This union of wisdom and compassion is the core of the Mahayana path as practiced in Tibet.

The practice and study of philosophy in Tibet are institutionalized within its great monastic universities, such as Sera, Drepung, and Ganden. Within these monasteries, the primary method of learning is formal debate (*tsödpa*). Monks spend many hours each day in lively, highly ritualized debates, where they use logic and scriptural citation to defend philosophical positions and refute the arguments of their opponents. This is not seen as a combative exercise but as a powerful tool for sharpening the intellect, deepening one’s understanding, and eliminating misconceptions about the nature of reality. The curriculum is vast and can take over two decades to complete, culminating in the awarding of a *Geshe* degree, equivalent to a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy. This rigorous system has produced centuries of brilliant scholars and practitioners and has preserved a rich and unbroken lineage of philosophical inquiry that continues to be studied and practiced both in Tibet and by the diaspora community around the world.

30) Cultural Etiquette

Observing and respecting cultural etiquette is paramount for any traveler wishing to have a meaningful and positive experience in Tibet. Tibetan culture is deeply infused with the principles of Buddhist compassion and respect, which guide social interactions. One of the most common and important gestures is the presentation of a *khata*, a traditional ceremonial scarf, usually made of silk. A khata is offered as a sign of respect, goodwill, and welcome. It is given to lamas, elders, hosts, and upon visiting monasteries or sacred sites. You may receive a khata upon arrival from your guide; it should be accepted with both hands. When offering one yourself, you should hold it with both hands and bow slightly. It is a gesture that embodies the warmth and hospitality of the Tibetan people. In general, using both hands to give or receive anything, from a gift to a cup of tea, is a sign of respect, whereas using a single hand can be seen as dismissive.

Respect for elders and religious figures is a cornerstone of Tibetan society. When addressing a lama or an elderly person, it is appropriate to use honorific titles and to be polite and deferential. Public displays of affection are uncommon and should be avoided. Physical contact, such as patting someone on the head, is considered highly inappropriate, as the head is believed to be the most sacred part of the body. Conversely, the feet are considered the lowest part, so one should avoid pointing their feet at another person or at a sacred object like an altar. When visiting monasteries and temples, there are specific rules of conduct to follow. You should always walk around stupas, prayer wheels, and other sacred objects in a clockwise direction. Dress modestly, ensuring your shoulders and knees are covered. Remove your hat upon entering a temple chapel, and do not touch the sacred statues or thangkas. Photography is often prohibited inside chapels, or may require a fee; always ask your guide for permission before taking pictures.

When interacting with local Tibetans, a friendly smile and a simple “Tashi Delek” (a traditional greeting meaning “good fortune” or “hello”) will be warmly received. If invited into a Tibetan home, it is a great honor. You will likely be offered butter tea or sweet tea; it is polite to take at least one sip. When your host refills your cup, which they will do frequently, it is customary to wait until they have finished before drinking again. A small gift from your home country is always a welcome gesture of appreciation for your hosts. Tipping is not a traditional part of Tibetan culture, but it has become an expected practice for guides and drivers in the tourism industry, as a way of showing gratitude for their hard work. By being mindful, observant, and respectful of these customs, visitors can demonstrate their appreciation for the unique and ancient culture of Tibet.

31) Sports and Recreation

Sports and recreation in Tibet are a vibrant blend of traditional pastimes rooted in the region’s unique culture and landscape, alongside a growing interest in modern sports. For centuries, Tibetan festivals have been the primary showcase for athletic prowess, with events that celebrate the skills essential for life on the high plateau. The most famous of these traditional sports are horse racing and archery. Tibetan horse festivals, such as the one held annually in Nagqu, are spectacular events where nomadic horsemen, renowned for their exceptional equestrian skills, compete in races and perform daring feats on horseback, often while dressed in magnificent traditional attire. These festivals are not just sporting events but major social gatherings, attracting people from all over the plateau for trade, celebration, and a reaffirmation of their cultural heritage. Archery also has a long and noble history in Tibet, and archery contests are a popular feature of many local festivals, including the New Year (Losar) celebrations.

Another uniquely Tibetan form of recreation is the *kora*, or ritual circumambulation. This is both a physical and spiritual exercise, a walking meditation that is a central part of religious life. Pilgrims and locals will walk in a clockwise direction around sacred sites, from the great monasteries and temples like the Jokhang in Lhasa, to sacred mountains like Mount Kailash, and holy lakes like Namtso. The kora around Mount Kailash, a grueling 52-kilometer trek at high altitude, is considered one of the most sacred pilgrimages in Asia, undertaken by Buddhists, Hindus, and Jains alike. This practice highlights how, in Tibetan culture, physical activity is often seamlessly integrated with spiritual devotion. Trekking and hiking are therefore natural extensions of this tradition, and the stunning landscapes of the Tibetan plateau offer some of the most spectacular trekking routes in the world.

In recent years, modern sports have also gained popularity in Tibet, particularly among the younger generation in urban areas. Basketball and football (soccer) have a growing following, with courts and pitches becoming more common in cities and towns. The influence of Chinese and international media has exposed young Tibetans to global sports stars and leagues, sparking interest in these games. Billiards and pool are also extremely popular leisure activities, with halls found in even small towns across the region. While traditional sports remain a vital and cherished part of Tibetan cultural life, particularly in rural and nomadic areas, the recreational landscape is gradually diversifying as Tibet becomes more connected to the wider world. The blend of ancient tradition and modern pursuits creates a unique and evolving sporting culture on the Roof of the World.

32) Environmental Concerns

The Tibetan Plateau, often called the “Third Pole,” is a region of immense global environmental significance, but its fragile high-altitude ecosystem faces a growing number of severe threats. As the source of Asia’s major rivers, the health of Tibet’s environment has profound implications for the water security of billions of people downstream in countries like India, China, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. The most pressing and well-documented concern is the impact of climate change. The plateau is warming at a rate more than twice the global average, leading to the rapid melting of its vast glaciers and the thawing of its extensive permafrost. This glacial retreat not only threatens the long-term stability of river flows but also increases the risk of natural disasters like glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs). The thawing of permafrost can damage infrastructure, such as roads and railways, and releases vast stores of trapped methane, a potent greenhouse gas that further accelerates global warming.

Another major environmental issue is the management of Tibet’s grasslands and water resources. The vast steppes of the Changtang and other regions are the foundation of the traditional nomadic pastoralist lifestyle. However, these grasslands are facing degradation due to a combination of factors, including climate change, overgrazing in some areas, and controversial government policies that have involved the large-scale settlement of nomads. These policies, while often framed as poverty alleviation and ecological protection measures, have been criticized for disrupting traditional land management practices and the cultural fabric of nomadic life. Furthermore, the construction of large-scale dams and water diversion projects on Tibet’s rivers, particularly by the Chinese government, is a source of significant concern. These projects have the potential to alter river hydrology, impact fragile aquatic ecosystems, and create geopolitical tensions with downstream countries that rely on the same water resources.

The exploitation of mineral resources also poses a threat to the Tibetan environment. The plateau is rich in minerals such as copper, gold, lithium, and chromium. The expansion of mining activities, often conducted by large state-owned enterprises, has raised serious concerns about water pollution, soil contamination, and the destruction of sensitive alpine habitats. Many of Tibet’s most sacred mountains and lakes, which are central to the region’s spiritual and cultural life, are also located in areas with significant mineral deposits, creating conflicts between economic development and cultural and environmental preservation. While the Chinese government has stated its commitment to “ecological civilization” and has established an extensive network of nature reserves across the plateau, balancing the pressures of economic growth with the urgent need to protect the unique and globally important environment of the Tibetan Plateau remains a critical and ongoing challenge.

33) Marriage & Courtship

Marriage and courtship in Tibetan culture are fascinating traditions that blend ancient customs with the practicalities of life on the high plateau. Historically, marriages were often arranged by the parents, with astrological compatibility playing a significant role in the selection of a partner. While arranged marriages are less common today, especially in urban areas, family approval remains a crucial part of the courtship process. When a young man is interested in a woman, his family will often send an intermediary to the woman’s family to express his interest and present gifts. If the initial approach is welcomed, a series of formal visits and gift exchanges will follow, solidifying the bond between the two families long before the wedding itself. These exchanges are rich in symbolism and are a vital part of the social fabric, reinforcing community ties. The engagement period is a time for the families to get to know each other and for the couple to prepare for their new life together.

One of the most unique aspects of traditional Tibetan marriage was the practice of polyandry, where a woman would marry two or more brothers. This custom, while now rare, was a pragmatic solution to the challenges of life in a harsh environment. It prevented the division of family property, particularly land and herds, ensuring the economic stability of the household from one generation to the next. In modern Tibet, monogamy is the standard form of marriage. The wedding ceremony itself is a vibrant and joyous affair, often lasting several days and filled with feasting, singing, and dancing. The bride and groom are dressed in elaborate traditional costumes, and the ceremony is rich with Buddhist symbolism and rituals performed to bring blessings, happiness, and prosperity to the new couple. The presentation of *khata* (ceremonial scarves) is a central part of the celebration, with guests offering them to the bride and groom as a sign of their good wishes.

34) Work Opportunities

Work opportunities in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) have been fundamentally reshaped in the modern era, reflecting the region’s state-driven economy and its ongoing process of modernization. The traditional occupations of subsistence farming and nomadic pastoralism, which for centuries were the mainstay of the Tibetan workforce, still employ a significant portion of the rural population. In the fertile river valleys, farmers cultivate highland barley, wheat, and rapeseed. On the vast northern plateau, nomadic herders continue to raise yaks and sheep, moving with their herds according to the seasons. However, the Chinese government has been actively implementing policies to modernize these sectors, introducing new agricultural techniques and encouraging the settlement of nomads into permanent housing, a policy aimed at poverty alleviation and grassland management but which also has profound impacts on the traditional way of life.

Beyond the traditional sectors, the largest source of formal employment in the TAR is the public sector. The regional government, along with its various departments, bureaus, and state-owned enterprises, is a major employer. This includes jobs in administration, healthcare, education, and infrastructure projects. The massive investment by the central government in building roads, railways, airports, and other infrastructure has created a significant number of jobs, particularly in the construction and transportation industries. However, there has been criticism that these projects often bring in a large number of skilled and unskilled workers from other parts of China, limiting the opportunities available to the local Tibetan population, particularly for higher-paying and more skilled positions.

The tourism industry has been designated as a pillar of the Tibetan economy and is a growing source of work opportunities. This includes jobs as tour guides, drivers, hotel staff, and restaurant workers. There are also opportunities for local artisans to sell traditional handicrafts, such as thangka paintings, carpets, and jewelry, to tourists. However, the tourism industry is tightly controlled by the government, and opportunities for Tibetans to own and operate their own large-scale tourism businesses can be limited. For foreign nationals, direct work opportunities within the TAR are virtually non-existent. Foreigners are not permitted to travel independently and must be on a pre-arranged tour, making it impossible to seek local employment. The only exceptions might be for individuals working for international organizations or in highly specialized roles with the explicit approval of the central government, which is extremely rare.

35) Education

The education system in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) has undergone a complete transformation from its traditional monastic roots to a modern, state-run system administered by the Chinese government. Historically, education in Tibet was almost exclusively the domain of the monasteries. Monastic institutions served as the centers of learning, providing a rigorous education in Buddhist philosophy, logic, debate, literature, and art. This education was primarily for monks and was not accessible to the general population, particularly in rural and nomadic areas, resulting in a low literacy rate among the laity. The curriculum was deeply religious, focused on preserving and transmitting the vast body of Buddhist knowledge. This system produced brilliant scholars and a highly sophisticated intellectual culture but was not designed to provide widespread, secular education.

Since the 1950s, the Chinese government has established a compulsory, state-funded public education system across the TAR, similar to the one in the rest of China. The government has invested heavily in building schools, from primary schools in remote villages to middle schools and high schools in towns and cities. As a result, literacy rates and school enrollment have increased dramatically. The official policy is one of “bilingual education,” with instruction theoretically provided in both Tibetan and Mandarin Chinese. However, in practice, Mandarin has become the primary language of instruction, particularly in middle and high school and for key subjects like math and science. While Tibetan language classes are still taught, critics argue that the system increasingly marginalizes the Tibetan language, making it difficult for Tibetan students to achieve fluency in their mother tongue and creating disadvantages for those who are not proficient in Mandarin when it comes to higher education and employment opportunities.

Access to higher education for Tibetan students is primarily through the Chinese national university system. After completing high school, students must take the national university entrance examination, the *gaokao*, which is administered in Chinese. Performance on this highly competitive exam determines a student’s eligibility for university admission. Tibet has its own university, Tibet University, in Lhasa, as well as several other specialized colleges. However, many students also attend universities in other parts of China. The government often provides preferential policies or lower admission scores for ethnic minority students, including Tibetans, to help increase their enrollment in higher education. The curriculum at the university level, like in the schools, is standardized and aligned with the national educational goals of the People’s Republic of China.

36) Communication & Connectivity

Communication and connectivity in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) have been revolutionized in the 21st century by massive state-led investment in infrastructure, transforming one of the world’s most remote and isolated regions into a place with widespread digital access. Historically, communication across the vast and rugged Tibetan plateau was incredibly difficult, relying on messengers on horseback. Today, the landscape is dramatically different. The Chinese government has made it a strategic priority to connect the TAR to the rest of the country, and this has included a huge rollout of modern telecommunications technology. The most significant development has been the expansion of the mobile phone network. Major Chinese operators have built an extensive network of cell towers, bringing mobile phone service and internet access to even many remote counties and townships.

The mobile phone is now the primary tool for communication and accessing the internet for the vast majority of people in Tibet. The availability of 4G networks is widespread in cities and towns, and is continuously expanding into more rural areas. This has had a profound social and economic impact, enabling new forms of social connection, commerce, and access to information and entertainment. Popular Chinese social media and messaging apps like WeChat are ubiquitous and are used for everything from daily conversation to mobile payments. For travelers, this means that staying connected is surprisingly easy. It is possible to purchase a Chinese SIM card and have reliable mobile data in most places you are likely to visit on a standard tour itinerary. Wi-Fi is also commonly available in hotels that cater to foreign tourists in cities like Lhasa and Shigatse.

While the physical infrastructure for connectivity is advanced, it is crucial to understand that all internet access in the TAR, as in the rest of China, operates behind the “Great Firewall.” This is a sophisticated system of internet censorship that blocks access to a wide range of foreign websites and social media platforms. Services like Google (including Gmail and Google Maps), Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, and many Western news websites are all inaccessible. To access these services, individuals must use a Virtual Private Network (VPN). However, the Chinese government has been cracking down on the use of VPNs, and their reliability can be inconsistent. It is advisable for travelers who wish to use these services to install and test a reputable VPN on their devices *before* they enter China. This dual reality—excellent physical connectivity combined with significant digital censorship—is the defining feature of the communication landscape in modern Tibet.

37) National Symbols

The national symbols of Tibet are a powerful and deeply resonant collection of emblems that reflect the nation’s unique geography, profound Buddhist faith, and distinct cultural identity. These symbols are cherished by Tibetans both within Tibet and in the diaspora community, serving as a focal point for their national and cultural consciousness. The most prominent and politically significant symbol is the Tibetan national flag, often referred to as the “Snow Lion Flag.” The flag is rich with symbolism: the snow-capped mountain in the center represents the great nation of Tibet; the two snow lions represent the unified spiritual and secular life; the three-colored jewel held aloft by the lions symbolizes the reverence for the “Three Jewels” of Buddhism (the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha); the sun with its twelve rays rising over the mountain represents the twelve ancient tribes of Tibet and the continuous enjoyment of freedom, light, and happiness; and the red and blue colors in the sky represent the protection of the nation by two guardian deities. The flag is banned within the People’s Republic of China, where its display is considered a separatist offense, but it is flown proudly by the Tibetan diaspora worldwide.

Religious symbols are intrinsically linked with Tibetan national identity. The most iconic of these is the Potala Palace in Lhasa. This magnificent architectural marvel, formerly the winter residence of the Dalai Lama, is a symbol of both the spiritual and temporal authority that once governed Tibet. Its white and red palaces perched high above the city are an unforgettable image that represents the heart of the nation. The eight-spoked Dharma Wheel (*Dharmachakra*), often depicted with two deer, is another central symbol, representing the Buddha’s teachings and the path to enlightenment. Prayer flags (*lung-ta*) are a ubiquitous sight across the Tibetan landscape. These colorful flags, printed with mantras and prayers, are hung in high places so that the wind will carry the blessings and good fortune across the land. The endless knot, the vase of treasure, and the lotus flower are other important auspicious symbols from Buddhist iconography that are deeply woven into Tibetan art and culture.

The natural world provides another set of powerful symbols for Tibet. The majestic Snow Lion (*Gangs Seng*), a mythical beast that roams the high mountain peaks, is the national animal, symbolizing fearlessness, strength, and the pristine, snowy wilderness of the Tibetan plateau. It is so central to the national identity that Tibet is often referred to as the “Land of Snows.” The Himalayan Blue Poppy, a beautiful and rare flower that grows at extreme altitudes, is often considered the national flower, representing the unique and precious flora of the region. The Tibetan Mastiff, a large and ancient breed of dog, is a symbol of protection and loyalty. The magnificent wild yak, which thrives in the harsh environment of the Changtang plateau, embodies the untamed spirit and resilience of the land and its people. Together, these symbols create a rich visual language that tells the story of Tibet’s faith, its history, and its profound connection to the “Roof of the World.”

| Symbol Category | Symbol Name / Description |

|---|---|

| National Flag | The “Snow Lion Flag” with a mountain, two snow lions, a sun, and colored rays. |

| Mythical National Animal | Snow Lion (Gangs Seng) |

| Unofficial National Flower | Himalayan Blue Poppy (Meconopsis) |

| Iconic Fauna | Yak, Tibetan Antelope (Chiru), Kiang (Tibetan Wild Ass) |

| Iconic Flora | Rhododendron, Saussurea (Snow Lotus) |

| Architectural Symbol | The Potala Palace in Lhasa |

| Religious Symbol | The Dharma Wheel (Dharmachakra), Prayer Flags (Lung-ta) |

| Cultural Symbol | Khata (Ceremonial Scarf), Thangka (Scroll Painting) |

| Cultural Symbol | Tibetan Prayer Wheel |

38) Tourism

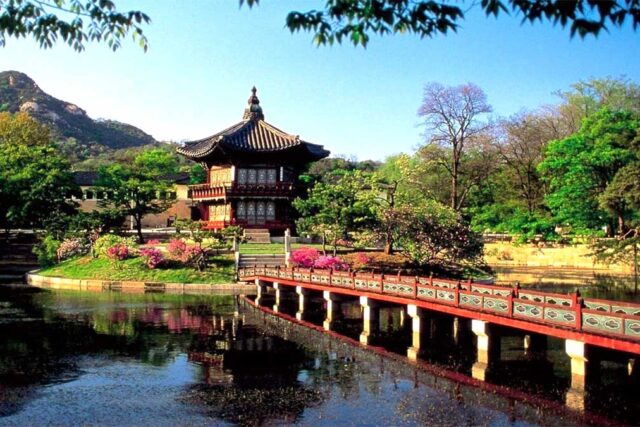

Tourism in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) offers a journey that is unlike any other on Earth, a chance to step into a world of profound spirituality, breathtaking high-altitude landscapes, and a deeply rooted, ancient culture. However, travel to Tibet is a unique and highly regulated experience that requires careful planning. Independent travel for foreign passport holders is not permitted. All international tourists must travel as part of an organized tour with a licensed travel agency. This means your entire itinerary, including your accommodation, transportation, and the sites you will visit, must be pre-arranged. A local Tibetan guide must accompany you at all times. This structure ensures that travel is controlled, but it also provides a hassle-free experience where all the complex logistics are handled for you. The journey typically begins in Lhasa, the spiritual and historical heart of Tibet. Here, visitors can explore the awe-inspiring Potala Palace, the sacred Jokhang Temple, and the bustling Barkhor Street, where pilgrims perform their ritual kora amidst a vibrant market.

Beyond Lhasa, the tours unveil the staggering beauty of the Tibetan plateau. A classic itinerary takes travelers along the Friendship Highway towards the Nepal border, a route that offers some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. This journey includes visits to the historic city of Gyantse, with its magnificent multi-tiered Kumbum stupa, and Shigatse, the home of the sprawling Tashilhunpo Monastery, the traditional seat of the Panchen Lama. Along the way, the road traverses high mountain passes that offer panoramic views of the Himalayas, including, on a clear day, the magnificent north face of Mount Everest (Chomolungma). Visiting the Everest Base Camp on the Tibetan side is a highlight for many, a chance to stand in the shadow of the world’s highest peak. Other popular destinations include the sacred, turquoise-colored Yamdrok Lake and Namtso Lake, one of the highest saltwater lakes in the world, whose celestial beauty is a truly unforgettable sight. For the more adventurous, a pilgrimage trek around the sacred Mount Kailash in far-western Tibet is considered the journey of a lifetime.

39) Visa and Entry Requirements

The visa and entry requirements for traveling to the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) are unique and multi-layered, requiring more than just a standard visa for the People’s Republic of China. It is a two-step process that is absolutely essential to understand and follow correctly. The first and most fundamental requirement for any foreign national is to obtain a Chinese visa. You must apply for a standard Chinese tourist visa (L-visa) from a Chinese embassy or consulate in your home country. It is critically important that when you apply for your Chinese visa, you do *not* mention Tibet as part of your itinerary on the application form. Visa applications that list Tibet as a destination are often delayed or rejected. Instead, you should list other major Chinese cities like Beijing, Shanghai, or Chengdu as your travel destinations. Your travel agency will provide you with a suitable itinerary for the visa application.

Once you have a valid Chinese visa, the second and equally crucial step is to obtain a Tibet Travel Permit, sometimes called a Tibet Entry Permit. This permit is issued by the Tibet Tourism Bureau in Lhasa and is the official document that allows a foreign passport holder to enter and travel within the TAR. This permit cannot be applied for independently. It can only be obtained by a licensed Tibetan travel agency on your behalf after you have booked a tour package with them. To apply, you will need to send scanned copies of your passport and your Chinese visa to the agency. The agency will then submit the application to the Tibet Tourism Bureau. The processing time for the permit can take several weeks, so it is essential to book your tour and submit your documents well in advance of your planned travel dates. The original permit will be delivered to your hotel in the Chinese city you are departing from for Tibet, as you will need to show it to board your flight or train to Lhasa.

In addition to the main Tibet Travel Permit, further permits may be required depending on your itinerary. If you plan to travel to “unopened” or remote areas of the TAR, such as Mount Everest Base Camp or Mount Kailash, you will also need an Aliens’ Travel Permit, which is issued by the Public Security Bureau (PSB) in Lhasa after your arrival. If your tour involves visiting any military-sensitive areas, a Military Permit will also be required. Your travel agency will handle all of these additional permit applications for you as part of your tour package. It is important to remember that these regulations can change, so it is vital to work closely with a reputable and experienced travel agency. They will have the most up-to-date information and will guide you through the entire process, ensuring that you have all the necessary documentation for a smooth and legal journey to the Roof of the World.

40) Useful Resources

As independent travel to the Tibet Autonomous Region is not permitted for foreign passport holders, there are no official government tourism websites aimed at international independent travelers. All travel must be arranged through a licensed travel agency.

Reputable international and local travel agencies specializing in Tibet tours are the primary resource for planning a trip. They handle all permits, itineraries, and bookings. Examples include Tibet Vista, Great Tibet Tour, and numerous others.

The Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in your home country is the official source for obtaining the necessary Chinese visa, which is the first step before a Tibet permit can be applied for.

Websites like Lonely Planet and other major travel guides can provide general information and context about Tibet, but for practical and current travel regulations, a licensed travel agency is the only reliable source.

Leave a Reply