CRITICAL TRAVEL ADVISORY: DO NOT TRAVEL TO YEMEN

Yemen is currently experiencing a catastrophic humanitarian crisis and an ongoing, complex civil war. All major foreign governments, including those of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and European Union member states, strongly advise their citizens against all travel to any part of Yemen. The security situation is extremely volatile and dangerous.

There is a very high threat of terrorism, kidnapping, armed conflict, and civil unrest. Airstrikes, shelling, and ground clashes are widespread. Basic services and infrastructure, including food, water, electricity, and medical care, have collapsed in many areas. Foreign nationals are at an extreme risk of being caught in the violence or being targeted for abduction. Consular services are non-existent within Yemen, and the ability of foreign governments to provide assistance to their citizens is effectively zero.

This guide is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It is intended to offer insight into the rich history, culture, and geography of Yemen, but it must not be interpreted as an encouragement or endorsement of travel to the country at this time. The information within describing sites and activities should be understood in a historical context, not as a reflection of current, safe possibilities. It is impossible to travel safely in Yemen at this time.

🇾🇪 Yemen Informational Guide

Table of Contents

- 21) Brief History

- 22) Geography

- 23) Politics and Government

- 24) Law and Criminal Justice

- 25) Foreign Relations

- 26) Administrative Divisions

- 27) Economy & Commodities

- 28) Science and Technology

- 29) Philosophy

- 30) Cultural Etiquette

- 31) Sports and Recreation

- 32) Environmental Concerns

- 33) Marriage & Courtship

- 34) Work Opportunities

- 35) Education

- 36) Communication & Connectivity

- 37) National Symbols

- 38) Tourism (Historical Context)

- 39) Visa and Entry Requirements

- 40) Useful Resources

21) Brief History

Yemen’s history is one of the most ancient and storied in the world, a rich narrative stretching back millennia from the heart of the Arabian Peninsula. Known to the ancient Romans as *Arabia Felix* (“Fortunate Arabia”), the region was blessed with greater rainfall than the surrounding deserts, allowing for flourishing agriculture and prosperous kingdoms. It was a crucial hub on the ancient incense and spice trade routes, connecting the Mediterranean with India and East Africa. This wealth gave rise to powerful civilizations, including the legendary Kingdom of Sheba, associated with the biblical Queen of Sheba, and the later Himyarite Kingdom. These kingdoms built remarkable cities, developed sophisticated irrigation systems, most famously the Great Dam of Marib, and left behind a legacy of unique art, architecture, and script. The region was a vibrant center of culture and commerce, interacting with civilizations from Rome to Persia long before the rise of Islam.

The 7th century marked a pivotal turning point with the arrival of Islam, which was swiftly adopted by the Yemeni tribes. Yemen became a vital part of the early Islamic world, and its people played a significant role in the early Islamic conquests. Over the following centuries, the region was often ruled by local dynasties, most notably the Zaydi imams, who established a line of theological and political rule in the northern highlands that would last, with interruptions, for over a thousand years. This long period of Zaydi rule shaped a distinct cultural and religious identity in the north. In the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire asserted control over parts of Yemen, particularly the coastal Tihama plain, but its rule was often tenuous and contested by the highland tribes. In the 19th century, another foreign power, the British, established a presence in the south, seizing the port of Aden in 1839 to serve as a vital coaling station for ships on the route to India. This created a lasting division, with the north under Ottoman and later Zaydi influence, and the south under British control.

This division defined Yemen’s 20th-century history. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the north became the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, ruled by the Zaydi imam. The south remained the British Protectorate of Aden. A 1962 revolution in the north overthrew the imamate and established the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen). Meanwhile, a nationalist struggle in the south led to British withdrawal in 1967 and the creation of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen), the only Marxist state in the Arab world. For two decades, the two Yemens existed side-by-side, often in a state of conflict. The end of the Cold War paved the way for their unification in 1990, creating the modern Republic of Yemen. However, the unification process was fraught with challenges, leading to a brief civil war in 1994 and persistent political and economic grievances. These unresolved tensions, combined with poverty, corruption, and sectarian divisions, created a fragile state that ultimately collapsed into the devastating civil war that began in 2014 and continues to this day, leading to the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

22) Geography

The geography of Yemen is remarkably diverse and dramatic, setting it apart from its largely desert neighbors on the Arabian Peninsula. Situated at the southern tip of the peninsula, it is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast, with a long coastline along the Red Sea to the west and the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the south. This strategic location has made it a maritime crossroads for millennia. The country’s topography is defined by a striking contrast between a hot, humid coastal plain and a rugged, mountainous interior. The western coastal plain, known as the Tihama, is a flat and arid strip of land running along the Red Sea. It is characterized by high temperatures, extreme humidity, and a landscape of sand dunes and scrubland. This region has historically been home to important port cities like Hodeidah and Mocha, the latter being the original source of the world-famous coffee trade.

Rising dramatically from the Tihama are the Yemeni Highlands, a complex series of mountain ranges and high plateaus that form the backbone of the country. This mountainous region receives significantly more rainfall than the rest of the peninsula, a result of seasonal monsoons. This rainfall has allowed for the development of sophisticated terraced agriculture that has been practiced for thousands of years, carving the mountainsides into stunning, verdant landscapes. These highlands, with peaks reaching over 3,600 meters (12,000 feet), are home to the majority of Yemen’s population and its historic capital, Sana’a, one of the highest capital cities in the world. The mountains create a temperate climate, a stark contrast to the scorching heat of the coast and the eastern deserts. This is the heartland of Yemeni culture, known for its unique tower-house architecture and the cultivation of coffee and qat.

To the east of the highlands, the landscape descends into the vast and arid expanse of the Ramlat al-Sab’atayn desert, which eventually merges with the Rub’ al Khali (the Empty Quarter), the largest sand desert in the world. This region is sparsely populated, home to Bedouin tribes and the location of much of Yemen’s oil and gas reserves. A truly unique and globally significant part of Yemen’s geography is the island of Socotra, located in the Arabian Sea. Often described as the “Galapagos of the Indian Ocean,” Socotra has been isolated for millions of years, resulting in an extraordinary level of biodiversity. Its otherworldly landscape is home to hundreds of plant and animal species found nowhere else on Earth, including the iconic and bizarre Dragon’s Blood Tree and the bulbous Bottle Tree. This unique natural heritage has earned Socotra a designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

23) Politics and Government

The political situation and system of government in Yemen are currently fractured and in a state of profound collapse due to the ongoing civil war that began in late 2014. Before the conflict, the Republic of Yemen operated as a presidential republic. The 1991 constitution (amended in 2001) established a system with a president elected by popular vote for a seven-year term, who served as the head of state, and a prime minister, appointed by the president, who served as the head of government. The legislature was bicameral, consisting of a 301-member elected House of Representatives and a 111-member appointed Shura Council. For over three decades, the political landscape was dominated by President Ali Abdullah Saleh and his party, the General People’s Congress (GPC). The 2011 Arab Spring protests forced Saleh to step down, leading to a transitional government under his vice president, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi. This transitional process, however, ultimately failed and collapsed into the current conflict.

Today, there is no single, functioning central government with authority over the entire country. Governance is violently contested and divided between two primary entities. On one side is the internationally recognized government, the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC). The PLC was formed in 2022, with President Hadi transferring his powers to this eight-member council. It is backed by a military coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates and is currently based temporarily in Aden and Riyadh. The PLC is recognized by the United Nations and the international community as the legitimate government of Yemen. However, its practical control on the ground is limited, mostly confined to the southern and eastern parts of the country, and it is itself composed of various factions with competing interests and military forces.

On the other side is the de facto authority in the north, particularly in the capital, Sana’a, and the most densely populated regions of the country. This authority is led by the Ansar Allah movement, more commonly known as the Houthis. The Houthis govern through a body called the Supreme Political Council. They control most of the institutions of the former state in the areas under their control, including ministries, the judiciary, and the security forces. This Houthi-led authority is not internationally recognized (with the exception of Iran) but holds firm administrative and military control over the territory it occupies. This political fracture has resulted in the complete breakdown of national governance. The country lacks a unified legal system, a national economy, or a single security apparatus. Instead, it is a patchwork of territories controlled by different armed groups, with the internationally recognized government and the Houthi authorities being the two largest, but by no means the only, power brokers in a devastating and protracted conflict.

24) Law and Criminal Justice

The formal legal system of Yemen, as it existed before the collapse of the state, is a complex mixture of different legal traditions. Its foundation is Islamic law (Shari’a), which is declared by the constitution to be the source of all legislation. This is supplemented by influences from Ottoman law, English common law (which was influential in the former British protectorate of Aden), and the Egyptian civil code, which itself was derived from the Napoleonic French code. This created a hybrid system where commercial and civil laws often resembled those of other Arab nations, while family and personal status law was more directly based on Shari’a principles. The formal court system was structured hierarchically, with Courts of First Instance, Courts of Appeal, and a Supreme Court in Sana’a, which served as the highest court of appeal for the entire country. The system was designed to provide a unified legal framework for the nation following the unification of North and South Yemen in 1990.

However, the outbreak of the civil war in 2014 has led to the complete fracture and breakdown of this unified legal and criminal justice system. There is no longer a single, functioning judicial authority with jurisdiction over the entire country. Instead, the legal landscape is divided and reflects the political and military division of Yemen. In the areas controlled by the internationally recognized government (the Presidential Leadership Council), efforts have been made to maintain the formal court structures, but their capacity is extremely limited due to the conflict, lack of resources, and insecurity. The judicial system in these areas is fragmented and struggles to function effectively.

In the northern highlands, including the capital Sana’a, which are controlled by the Houthi movement, a separate judicial system has been established. The Houthi authorities have taken over the existing court buildings and ministries and operate a legal system that they state is based on their interpretation of Islamic law, particularly the Zaydi school of jurisprudence. This system operates entirely independently of the internationally recognized government and international legal norms. In practice, across the entire country, formal legal protections have been largely replaced by the rule of armed groups. Justice is often administered by local commanders or tribal authorities, with little to no due process. Arbitrary detention, torture, and summary executions are widespread, as documented by numerous human rights organizations. For any individual in Yemen, access to fair and impartial justice is practically non-existent, and personal safety is dictated by the local security situation and the whims of the controlling armed faction.

25) Foreign Relations

The foreign relations of Yemen are currently as fractured and contested as the country itself, with no single entity able to represent the nation on the world stage with unified authority. The ongoing civil war has created a situation where two main power blocs conduct separate and opposing diplomatic activities. The internationally recognized government of Yemen, currently embodied by the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), maintains formal diplomatic relations with the majority of the world’s countries and holds Yemen’s seat at the United Nations. The PLC’s foreign policy is overwhelmingly shaped by its reliance on its primary backers, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. These two Gulf nations lead a military coalition that has been fighting in support of the recognized government since 2015. Consequently, the PLC’s foreign relations are closely aligned with the geopolitical interests of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, and it actively engages with Western powers like the United States and the United Kingdom, who also provide military and diplomatic support to the coalition.

This internationally recognized government uses its diplomatic platform to legitimize its position, condemn the actions of the Houthi movement, and call for international pressure and sanctions against its rivals. It participates in UN-led peace talks and engages with international humanitarian organizations to coordinate aid delivery to the areas under its control. The foreign policy of the PLC is centered on the goals of restoring its authority over the entire country, ending the Houthi “coup,” and reaffirming Yemen’s place within the traditional Arab and international political order. Its diplomatic efforts are focused on securing continued military, economic, and humanitarian support from its international partners to sustain its existence and its war effort.

In opposition, the Houthi movement (Ansar Allah), which controls the capital, Sana’a, and most of northern Yemen, conducts its own de facto foreign policy, although it lacks formal international recognition. The Houthis’ primary international relationship is with the Islamic Republic of Iran, which has provided them with political, financial, and military support, including advanced weaponry like drones and ballistic missiles. The Houthi authorities view their struggle as a resistance against foreign aggression, led by Saudi Arabia and its Western allies. Their foreign policy rhetoric is strongly anti-American, anti-Saudi, and anti-Israeli. They have established relations with other entities in Iran’s “Axis of Resistance,” such as Hezbollah in Lebanon. In the context of the Red Sea, the Houthis have demonstrated their ability to impact global geopolitics by launching attacks on international shipping, framing these actions as a response to the war in Yemen and in solidarity with the Palestinian cause. This has brought them into direct military confrontation with a U.S.-led naval coalition, further complicating the international dimensions of the conflict.

26) Administrative Divisions

The formal administrative structure of the Republic of Yemen, as established by law before the outbreak of the current conflict, divides the country into two main tiers of subnational governance: governorates and districts. The primary administrative division is the governorate (*muhafazah*). The country is officially divided into 22 governorates, including the capital city of Sana’a, which is designated as a separate municipality with the status of a governorate (*Amanat al-Asimah*), and the unique Socotra Archipelago, which was established as its own governorate in 2013. These governorates serve as the main administrative units for the implementation of central government policy and the delivery of public services. Each governorate is headed by a governor, who, in the pre-conflict system, was appointed by the president and acted as the central government’s chief representative in the region.

The governorates of Yemen vary enormously in terms of their population, geography, and economic characteristics. They range from densely populated and mountainous governorates in the highlands like Ibb and Taiz, to vast and sparsely populated desert governorates in the east like Hadhramaut and Al Mahrah. The coastal governorates, such as Hodeidah and Aden, are centered around major port cities. This formal structure was designed to provide a framework for governing the entire territory of the unified state, encompassing the diverse regions of both former North and South Yemen. The capital, Sana’a, being the political and demographic heart of the nation, was given its own special administrative status to manage its large urban population.

In practice, however, this formal administrative map has been completely fractured by the ongoing civil war. The *de jure* administrative divisions exist on paper, but *de facto* control on the ground is contested and divided among various armed factions. The Houthi movement controls the majority of the northern governorates, including the capital Sana’a, Hodeidah, and the most populous highland regions. The internationally recognized government, represented by the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), and its allied forces control other governorates, such as Aden and parts of Taiz and Marib. The Southern Transitional Council (STC), a separatist group, exerts significant control over several southern governorates, including the city of Aden, despite being nominally allied with the PLC. Furthermore, other local militias and tribal forces hold sway in different areas. This means that the official governorate boundaries no longer reflect a coherent system of governance. Instead, they have become frontlines in a complex conflict, with different authorities controlling different parts of the country, making unified national administration impossible.

27) Economy & Commodities

Prior to the outbreak of the devastating civil war in 2014, the Yemeni economy was already one of the poorest and least developed in the Arab world. It was heavily reliant on a few key sectors and was characterized by high unemployment, widespread poverty, and significant structural weaknesses. The most important commodity and the primary source of government revenue was oil. Yemen is not a major oil producer on the scale of its Gulf neighbors, but oil exports historically accounted for the vast majority of its export earnings and funded a large portion of the state budget. The country’s oil reserves are modest and were already in decline before the conflict began. Natural gas was an emerging sector, with the development of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility. However, the over-reliance on these hydrocarbon resources made the economy highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global energy prices.

Beyond the oil and gas sector, agriculture has traditionally been a cornerstone of the Yemeni economy and way of life, employing a large percentage of the population. The country’s diverse geography allows for the cultivation of a variety of crops. The terraced highlands are famous for producing high-quality coffee, with Mocha coffee being one of Yemen’s most famous historical exports. The cultivation of qat, a mild stimulant leaf that is chewed by a large portion of the population, is also a massive part of the agricultural economy, though it has been criticized for its high water consumption. Other important agricultural products include grains, fruits, and vegetables. Fishing along Yemen’s long coastline was another important sector, providing food and employment. However, the agricultural sector was severely hampered by chronic water scarcity, a problem that has reached crisis levels in many parts of the country.

The ongoing conflict has led to the complete and catastrophic collapse of the Yemeni economy. The war has shattered the country’s productive capacity, destroyed critical infrastructure, and created one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world. Oil and gas production and exports have been severely disrupted, depriving the state of its main source of revenue. The conflict has split the country’s economic institutions, including the Central Bank, leading to hyperinflation and the collapse of the national currency, the Yemeni rial. A de facto blockade on ports and airports has crippled imports of food, fuel, and medicine, leading to severe shortages and soaring prices. Businesses have closed, and unemployment has skyrocketed. The economy now is primarily a war economy, and the vast majority of the population is dependent on humanitarian aid from international organizations for their basic survival. There are no functioning economic commodities to speak of in the traditional sense; the most critical commodity is now humanitarian aid itself.

28) Science and Technology

The history of science and technology in Yemen is a story of remarkable ancient ingenuity followed by a modern period of profound struggle and collapse. In antiquity, Yemen was a hub of sophisticated engineering and scientific knowledge, particularly in the fields of hydraulics and architecture. The most legendary example of this is the Great Dam of Marib, an engineering marvel first built in the 8th century BC. This massive earth and stone dam created a vast irrigation system that turned the surrounding desert into a fertile oasis, supporting the prosperous Sabaean kingdom for over a thousand years. The construction and maintenance of this dam required a deep understanding of hydrology, engineering, and resource management. Similarly, the unique multi-story tower-houses of ancient Sana’a and Shibam showcase an advanced knowledge of architecture and building materials, designed to create comfortable living spaces in varied climates. These historical achievements demonstrate a rich heritage of practical and applied science.

In the Islamic Golden Age, Yemeni scholars also contributed to fields like astronomy, medicine, and mathematics. The country was known for its centers of learning, and its strategic location on trade routes facilitated the exchange of knowledge. However, in the modern era, Yemen has struggled to develop a robust science and technology sector. Before the current conflict, the country had established several universities, including Sana’a University, and technical institutes. There were efforts to build a national scientific research capacity, but these were severely hampered by a lack of funding, limited resources, political instability, and a “brain drain” of skilled professionals seeking better opportunities abroad. The country’s infrastructure for science and technology was minimal, and its contribution to global scientific output was very low.

The ongoing civil war since 2014 has completely decimated Yemen’s nascent science and technology sector. The conflict has led to the widespread destruction of universities, research facilities, and public infrastructure. The education system has collapsed, preventing the training of a new generation of scientists and engineers. The ongoing humanitarian crisis and economic collapse have forced the remaining skilled professionals to flee the country or to focus solely on survival. There is currently no functioning national system for scientific research or technological development. Any application of technology is now primarily focused on the war effort, with the use of drones and other military technologies by the conflict’s various factions, or on the efforts of international humanitarian organizations, which use satellite technology and data analysis to monitor the crisis and coordinate aid delivery. The once-proud scientific heritage of Yemen lies dormant, buried under the rubble of a catastrophic conflict.

29) Philosophy

The philosophical tradition in Yemen is deeply and inextricably intertwined with its rich history of Islamic scholarship and jurisprudence. While philosophy as a separate, secular discipline did not develop in the same way as in the West, Yemen has been a crucible of profound theological and legal thought for centuries, producing schools of interpretation and intellectual debates that have shaped the culture and society of the region. The country’s mountainous and often remote geography allowed for the development and preservation of distinct schools of Islamic thought, most notably the Zaydi school of Shi’a Islam, which became the dominant force in the northern highlands for over a millennium. Zaydism itself is a philosophical and political school that emphasizes justice, the importance of rising up against an unjust ruler, and a rationalist approach to theology that was influenced by the Mu’tazila school of thought.

Zaydi scholarship produced a vast body of literature on theology, law, and ethics. It fostered a tradition of intellectual inquiry that valued reason and debate in the interpretation of religious texts. This created a rich philosophical environment within the Zaydi seminaries of the north. In parallel, the coastal and southern regions of Yemen were historically centers of the Shafi’i school of Sunni Islam. This also produced a vibrant tradition of legal and ethical philosophy, contributing to the broader intellectual currents of the Islamic world. The city of Tarim in the Hadhramaut region, for example, became a renowned center of Sufi learning and spirituality, developing a philosophical approach that emphasized inner purification, mysticism, and the direct experience of the divine. The interplay between these different schools of thought created a dynamic intellectual landscape within Yemen.

In addition to this rich theological and legal philosophy, Yemen has a powerful poetic tradition that serves as a major vehicle for expressing philosophical ideas about life, love, honor, and society. Poetry is a deeply respected art form in Yemeni culture, and poets have historically been important social and political commentators, using their craft to explore profound existential themes and to reflect on the nature of justice and community. In the modern era, Yemeni intellectuals have grappled with the challenges of colonialism, nationalism, and the search for a modern identity, leading to new political and social philosophies. However, the current conflict has had a devastating impact on this intellectual heritage. The destruction of cultural sites, the collapse of the education system, and the polarization of society have silenced many voices and have largely replaced philosophical debate with the stark and brutal ideology of war.

30) Cultural Etiquette

Cultural etiquette in Yemen is deeply rooted in Islamic traditions, ancient Arab customs, and a strong sense of tribal and family honor. Hospitality is a cornerstone of the culture and is considered a sacred duty. A guest is treated with immense respect and generosity, regardless of their background. If invited into a Yemeni home, you will be warmly welcomed and likely offered coffee (*qahwa*) or tea. It is considered polite to accept this offering. When socializing, greetings are important and can be lengthy, involving inquiries about health, family, and well-being. Handshakes are common between men, but it is important to wait for a woman to offer her hand first; a polite nod is often the appropriate greeting for a woman. As in many Muslim cultures, the left hand is considered unclean, so you should always use your right hand to give or receive anything, particularly food.

Respect for elders and social hierarchy is paramount. When entering a room, you should greet the eldest person first. Modesty in dress and behavior is highly valued for both men and women. For visitors, this means dressing conservatively. Men should wear long trousers and shirts with sleeves, while women should wear loose-fitting clothing that covers their arms and legs, and a headscarf (*hijab*) is often required, especially when entering mosques or more conservative areas. Public displays of affection are entirely inappropriate. When photographing people, it is essential to ask for permission first, particularly when taking pictures of women. Yemeni society is largely gender-segregated, and men and women often socialize separately in private homes. Understanding and respecting these gender dynamics is crucial for any visitor.

A unique and central part of social life, particularly for men, is the afternoon gathering to chew qat. Qat is a leafy green plant that acts as a mild stimulant, and chewing it with friends and colleagues is a deeply ingrained social ritual. These gatherings, which can last for hours, are important occasions for socializing, discussing business, and debating politics. While a foreigner might be invited to a qat chew as a sign of hospitality, there is no obligation to partake. The concept of time is also more fluid than in the West; a strong emphasis is placed on personal relationships over strict punctuality. It is important to remember that these customs are part of a rich cultural heritage that has been tragically overshadowed by the current conflict. Any future visitor, in a time of peace, would need to approach this culture with immense sensitivity and respect.

31) Sports and Recreation

Before the devastating civil war, sports and recreation in Yemen were a source of national pride and a popular pastime, with football (soccer) being the undisputed king. The Yemeni national football team was a member of FIFA and the Asian Football Confederation, and its matches in international competitions would draw passionate support from across the country. The domestic football league, while not as well-funded or professionalized as those in other Middle Eastern countries, had a dedicated following, with clubs in major cities like Sana’a and Aden competing for the national title. On a grassroots level, football was played in streets, fields, and schoolyards everywhere, serving as a vital form of recreation and social interaction for young people in a country with limited entertainment options. The war, however, has had a catastrophic impact on the sport, with the league suspended, stadiums damaged, and the national team forced to play its “home” games in other countries.

Beyond football, traditional sports and recreational activities have long been a part of Yemeni culture, particularly in rural and tribal areas. These activities often celebrate the skills and prowess associated with the country’s rugged environment and history. Camel jumping is a spectacular traditional sport practiced by tribes in the southern part of the country, where young men showcase their agility and bravery by leaping over a line of camels. Archery and shooting have also been popular traditional pastimes, reflecting the importance of these skills in a tribal society. In the coastal regions, fishing and boating have always been central to both work and recreation. The unique island of Socotra, with its pristine waters, offered incredible opportunities for diving and snorkeling, though this was a nascent industry before the conflict.

For most Yemenis, recreation is often simpler and centered around social gatherings. The afternoon qat chew is the primary form of social recreation for a large segment of the male population, a time to relax, socialize with friends, and discuss the day’s events. Visiting family and friends is another central part of social life. Public parks and recreational facilities are limited, and the ongoing conflict has made public spaces unsafe in many areas. The war has effectively destroyed the fabric of normal life, including the ability to engage in sports and recreation. For children and young people, the loss of these outlets has been particularly devastating, robbing them of a chance to play, socialize, and enjoy a normal childhood. Any semblance of organized sport today is a testament to the incredible resilience of the Yemeni people in the face of unimaginable hardship.

32) Environmental Concerns

Yemen faces a nexus of catastrophic environmental challenges that were severe even before the current conflict and have now been pushed to the absolute brink by years of war. The most critical and existential of these is water scarcity. Yemen is one of the most water-stressed countries on Earth. Its groundwater resources, which the majority of the population depends on for drinking and agriculture, have been over-exploited for decades at an alarming and unsustainable rate. The water table in the Sana’a basin, for example, has been dropping by several meters per year. This crisis is driven by rapid population growth, inefficient irrigation techniques, and the widespread cultivation of qat, a water-intensive crop. The war has exacerbated this crisis exponentially. The destruction of water infrastructure, including pipes, pumps, and treatment plants, has left millions without access to safe drinking water, leading to the spread of waterborne diseases like cholera in one of the worst outbreaks in modern history.

Land degradation and desertification are another major environmental concern. Unsustainable agricultural practices, deforestation for firewood, and overgrazing have led to widespread soil erosion. This loss of fertile land threatens the country’s food security, which is already in a state of collapse due to the conflict and blockade. The war has also had a devastating impact on waste management. In cities across the country, sanitation systems have failed, and garbage collection has ceased, leading to mountains of uncollected waste in public spaces. This not only creates a severe public health hazard but also leads to the contamination of soil and water resources. The conflict has made any large-scale environmental protection or conservation programs completely impossible to implement.

A unique and globally significant environmental threat that has garnered international attention is the situation of the FSO Safer oil tanker. This decaying supertanker, moored off the coast of Hodeidah, holds over a million barrels of crude oil and has not been maintained since the start of the war. It has been described as a “ticking time bomb,” with the potential for a massive oil spill that would be four times larger than the Exxon Valdez disaster. Such a spill would cause an unprecedented environmental catastrophe in the Red Sea, destroying coral reefs and marine ecosystems, crippling the fishing industry for coastal communities, and disrupting one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. While a UN-led operation has recently begun to transfer the oil to a new vessel, the long-term threat and the broader environmental collapse within Yemen remain a stark testament to how conflict can create a cascade of ecological disasters.

33) Marriage & Courtship

Marriage and courtship in Yemeni society are deeply rooted in tradition, family, and Islamic customs. The process is typically a family-oriented affair, where the union is seen as a bond between two families, not just two individuals. While personal choice has become more common, especially in urban areas, arranged marriages or marriages with strong family input remain the norm. The courtship process often begins when a young man’s family identifies a potential bride. An intermediary, usually a female relative, will approach the young woman’s family to gauge their interest. If the reception is positive, a more formal process of visits and negotiations between the families begins. The suitability of the match is considered based on factors like social standing, tribal affiliation, and family reputation. The consent of both the prospective bride and groom is required, but the process is guided heavily by the elders of the family.

Once an agreement is reached, the engagement is formalized, and the wedding preparations begin. Yemeni weddings are elaborate, joyous, and vibrant multi-day celebrations that are a central part of the cultural life. The festivities are strictly gender-segregated. The men’s party typically involves gatherings with music, dancing (such as the traditional *baraa* dance with daggers), and the chewing of qat. The bride’s celebration is centered around the henna party, a colorful and lively event where the bride’s hands and feet are adorned with intricate henna designs by her female relatives and friends. On the main wedding day, the bride wears a stunning and often very elaborate wedding outfit, sometimes covered in gold jewelry, and celebrates with her female guests. The groom will later join the women’s party to be with his bride. The wedding is a major community event, reinforcing social ties and celebrating the continuation of the family line. Unfortunately, the ongoing humanitarian crisis has placed immense financial strain on families, making these elaborate celebrations difficult, and has also led to a tragic increase in child marriage as a desperate coping mechanism for impoverished families.

34) Work Opportunities

It must be stated unequivocally that there are currently no work opportunities for foreign nationals in Yemen. The country is an active and extremely dangerous war zone, and any foreign presence is limited almost exclusively to a small number of hardened and highly experienced humanitarian aid workers, diplomats, and journalists operating under extreme risk and with extensive security protocols. The security situation, with widespread conflict, terrorism, and a very high threat of kidnapping, makes it impossible for any form of regular expatriate employment to exist. There are no functioning mechanisms for obtaining work permits for foreigners, and the legal and administrative systems required to support a foreign workforce have completely collapsed. Any attempt by a foreigner to seek work in Yemen would be exceptionally dangerous and reckless.

For the Yemeni people, the labor market has been utterly devastated by the ongoing conflict. The formal economy has imploded. The destruction of infrastructure, the de facto blockade of ports, the collapse of the currency, and the flight of capital have led to the closure of businesses across all sectors. The oil and gas industry, once the backbone of the state’s revenue, has been severely disrupted. The civil service, which was a major employer, has been fractured, and in many parts of the country, government workers have gone without salaries for years. The private sector has been decimated, with businesses unable to operate due to insecurity, lack of electricity, and the collapse of supply chains and consumer demand. As a result, unemployment has skyrocketed to catastrophic levels, particularly among the youth.

In the absence of a formal economy, the majority of the population has been forced into a desperate struggle for survival. The primary source of “work” for many is in the informal sector, which includes small-scale subsistence farming, petty trade, or day labor when it can be found. Many have become entirely dependent on humanitarian aid provided by international organizations like the UN World Food Programme. In many areas, the only significant source of employment is joining one of the various armed factions involved in the conflict. The war has not only destroyed the existing labor market but has also obliterated the country’s human capital, as the education system has collapsed and millions have been displaced, creating a lost generation whose prospects for future employment, even in a time of peace, have been severely compromised.

35) Education

The education system in Yemen is in a state of complete and catastrophic collapse due to the ongoing civil war. Before the conflict, Yemen had made significant progress in expanding access to education, with a national system that included nine years of compulsory basic education followed by three years of secondary education. The system was administered by the Ministry of Education, which set the curriculum for public schools across the country. There were several public universities, with Sana’a University being the oldest and largest, as well as a number of private universities and colleges. Despite this progress, the system faced immense challenges, including low enrollment rates (especially for girls in rural areas), a shortage of qualified teachers, and a lack of resources and adequate facilities. The literacy rate was among the lowest in the Arab world, reflecting the deep-seated poverty and historical underdevelopment of the country.

The conflict that began in 2014 has completely devastated this already fragile education system. According to the United Nations and other international aid organizations, the war has had a multifaceted and disastrous impact. A large number of schools have been damaged or completely destroyed by airstrikes and ground fighting. Many other school buildings have been repurposed to shelter displaced families or have been occupied by armed groups, rendering them unusable for education. This destruction of infrastructure has left millions of children with no school to attend. The education system has also been fractured along the political lines of the conflict, with different curricula being taught in areas controlled by the internationally recognized government and those controlled by the Houthi authorities, further dividing the nation.

The human toll on the education sector has been equally severe. Teachers have been one of the hardest-hit groups. In many parts of the country, public school teachers have not received regular salaries for years, forcing them to find other means of survival and leading to a massive teacher shortage. Those who continue to teach often do so as volunteers in incredibly difficult and dangerous conditions. For children, the risks are immense. The journey to school can be perilous due to the threat of shelling or unexploded ordnance. The psychological trauma of the war has had a profound impact on students’ ability to learn. The economic collapse has forced many families to pull their children out of school, either because they cannot afford the costs or because they need their children to work or beg to help the family survive. This has created a “lost generation” of Yemeni children who have been deprived of their right to education, a crisis that will have profound and long-lasting consequences for the future of the country, even if peace were to be achieved tomorrow.

36) Communication & Connectivity

The communication and connectivity infrastructure in Yemen has been severely degraded and fragmented by the ongoing civil war, making reliable communication a daily challenge for the population. Before the conflict, Yemen was already lagging behind its regional neighbors in terms of telecommunications development, but it had a functioning system with several mobile network operators and growing internet penetration, particularly in urban areas. The state-owned Public Telecommunications Corporation (PTC) was the dominant player, and several private mobile companies also operated. The infrastructure consisted of a network of cell towers, landlines, and submarine cables that connected the country to the global internet. This system, while limited, provided a vital link for commerce, social interaction, and access to information for millions of Yemenis.

The war has had a devastating impact on this infrastructure. Airstrikes and ground fighting have destroyed numerous cell towers, fiber optic cables, and central exchanges. The lack of electricity and fuel to power the remaining towers and equipment is a constant problem, leading to frequent and prolonged network outages. The de facto blockade on the country has made it extremely difficult to import the spare parts and equipment needed for repairs. As a result, mobile phone service and internet access are often sporadic, slow, and unreliable, even in major cities. The cost of these services has also skyrocketed due to the collapse of the economy and the currency, putting them out of reach for many impoverished families. The connectivity that does exist is often concentrated in urban centers, leaving many rural areas completely cut off.

Furthermore, the communication sector has become a tool in the conflict. The infrastructure is divided between the warring factions. The Houthi authorities in Sana’a control the dominant telecommunication networks and the main internet gateways, giving them the ability to monitor traffic, censor content, and periodically shut down internet access entirely. This control is used to suppress dissent and limit the flow of information that contradicts their narrative. Websites of news outlets, political opposition, and human rights organizations are widely blocked. This digital censorship, combined with the physical destruction of the network, has created an environment of extreme information poverty and has further isolated the Yemeni people from each other and the outside world. For the few international aid workers and journalists operating in the country, communication relies heavily on expensive and specialized satellite phones and internet terminals.

37) National Symbols

The national symbols of the Republic of Yemen are a collection of emblems that represent the country’s unified identity, its rich history, and its natural heritage. These symbols were adopted following the unification of North and South Yemen in 1990 and were intended to foster a sense of shared national pride. The most prominent symbol is the national flag. It is a simple but powerful tricolor, consisting of three equal horizontal bands of red, white, and black. This pan-Arab color scheme is shared by several other nations in the region. The red is said to symbolize the blood of martyrs shed in the struggle for independence and unity. The white represents a bright and peaceful future. The black band is a reminder of the country’s dark past under colonial rule and oppression. The flag is a symbol of the unified republic and is the one used by the internationally recognized government.

The national emblem, or coat of arms, of Yemen is centered on a golden eagle, known as the Eagle of Saladin, a symbol of Arab nationalism. The eagle has a scroll in its talons which bears the name of the country in Arabic: *al-Jumhūrīyah al-Yamanīyah* (The Republic of Yemen). On the eagle’s chest is a shield that depicts two of Yemen’s most iconic symbols: a coffee plant, representing the country’s famous historical export of Mocha coffee, and the Great Dam of Marib, a testament to Yemen’s ancient engineering prowess. To the left and right of the eagle are two crossed Yemeni flags, further reinforcing the national identity. This emblem powerfully combines symbols of Arab unity with specific representations of Yemen’s unique agricultural and historical heritage.

Yemen also has a rich array of natural and cultural symbols that are deeply ingrained in the national consciousness. While not all are officially designated, they are universally recognized as being quintessentially Yemeni. The Socotra Dragon’s Blood Tree (*Dracaena cinnabari*), with its unique, umbrella-like shape and red resin, is a globally recognized symbol of the unique biodiversity of the island of Socotra and Yemen as a whole. The national bird is the Arabian Golden-winged Grosbeak. Culturally, the *Jambiya*, a curved dagger worn by men in a decorative sheath on their belt, is perhaps the most iconic symbol of Yemeni manhood and cultural identity. The unique, multi-story tower-house architecture of the Old City of Sana’a and the ancient city of Shibam (often called the “Manhattan of the Desert”) are UNESCO World Heritage sites and powerful symbols of the country’s architectural ingenuity. These symbols, both official and cultural, are a poignant reminder of a rich and proud heritage that has been tragically overshadowed by the current conflict.

| Symbol Category | Symbol Name / Description |

|---|---|

| National Flag | A tricolor of red, white, and black horizontal bands. |

| National Coat of Arms | The Eagle of Saladin with a shield depicting a coffee plant and the Marib Dam. |

| National Anthem | “United Republic” |

| National Bird | Arabian Golden-winged Grosbeak |

| Iconic Flora | Socotra Dragon’s Blood Tree, Coffee Plant |

| Iconic Fauna | Arabian Leopard (critically endangered), Arabian Oryx |

| Cultural Symbol | Jambiya (curved dagger) |

| Iconic Architecture | The tower-houses of Sana’a and Shibam |

| Iconic Commodity | Mocha Coffee, Frankincense, Myrrh |

38) Tourism (Historical Context)

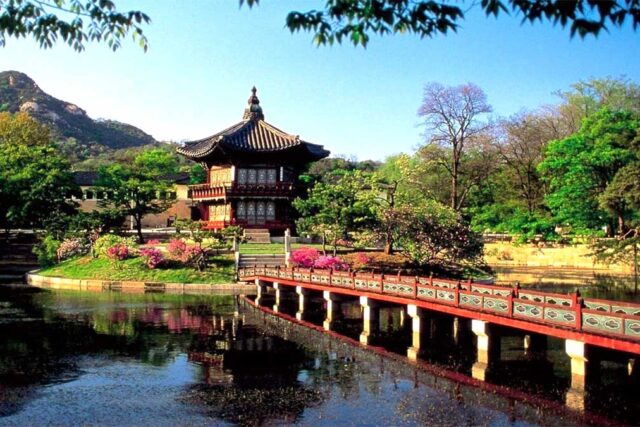

It is crucial to understand this section in a purely historical context, as tourism in Yemen is currently impossible due to the ongoing war. Before the conflict escalated in 2014, Yemen was a unique and breathtaking destination that attracted adventurous travelers and those with a deep interest in history, culture, and architecture. The country was home to four UNESCO World Heritage sites, each offering an unparalleled glimpse into the nation’s rich past. The Old City of Sana’a was a major draw, a living museum of stunning, multi-story tower-houses decorated with intricate white gypsum plasterwork (*qadad*). Wandering through its labyrinthine alleys, exploring the bustling souks, and admiring the ancient mosques was like stepping back in time. The ancient walled city of Shibam in the Hadhramaut valley, often dubbed the “Manhattan of the Desert,” was another architectural marvel, with its forest of mud-brick skyscrapers rising dramatically from the desert floor.

The island of Socotra was Yemen’s crown jewel for ecotourism and nature lovers. Its incredible and otherworldly biodiversity, with hundreds of endemic species like the Dragon’s Blood Tree and the Bottle Tree, made it a destination unlike any other on Earth. Travelers came for hiking, exploring the unique landscapes, and diving in its pristine marine environment. The historic town of Zabid, another UNESCO site, was a center of Islamic learning for centuries. Beyond these headline attractions, Yemen offered incredible trekking in the Haraz Mountains, exploration of ancient Himyarite ruins, and the chance to experience the warm hospitality of the Yemeni people. The country’s diverse landscapes, from the Red Sea coast to the high mountains and the vast deserts, provided a rich tapestry of experiences for those willing to venture off the beaten path. This tourism potential, however, has been completely extinguished by the war, with infrastructure destroyed and heritage sites damaged or at risk.

39) Visa and Entry Requirements

This section is provided for informational purposes only and reflects the situation as it would be in a time of peace. Currently, it is practically impossible for ordinary travelers to obtain a visa and enter Yemen safely and legally. Due to the ongoing civil war and the collapse of the central government, most Yemeni embassies and consulates around the world have suspended their regular visa services. The country’s borders, airports, and seaports are controlled by various armed factions, and there is no functioning, unified immigration authority. The security situation is extremely volatile, and any attempt to enter the country, even if a visa were obtainable, would be exceptionally dangerous. All foreign governments advise their citizens in the strongest possible terms against any travel to Yemen.

In a hypothetical, stable, post-conflict scenario, the visa policy of Yemen would require most foreign nationals to obtain a visa in advance of their travel. This would typically be done by applying at a Yemeni embassy or consulate in one’s country of residence. The application process would likely require a valid passport, a completed application form, passport-sized photographs, and possibly a letter of invitation or proof of a booked tour, particularly for tourists. It is probable that citizens of certain other Arab nations might be granted visa-free access or a visa on arrival, as is common with regional agreements. However, for most Western, Asian, and African travelers, pre-arranged visas would be the standard requirement. The specifics of the policy would be determined by the future government of a unified and peaceful Yemen.

It is important to reiterate that the current reality is one of closed doors and extreme danger. The main airport in the capital, Sana’a International Airport, has been largely closed to commercial international traffic for years due to the conflict and blockade. The airport in Aden, controlled by the internationally recognized government, operates on a very limited basis, but travel to and from this airport and the surrounding areas is still extremely hazardous. There is no safe, reliable, or legal pathway for tourism or business travel to Yemen at this time. Any information on visa requirements from before 2014 is completely outdated and irrelevant to the current situation. The only foreigners entering the country are typically accredited journalists and humanitarian aid workers who undergo a rigorous and high-risk vetting and security process through the United Nations and the warring parties.

40) Useful Resources

Given the current situation, traditional tourism resources are not applicable. The following resources are provided to offer accurate information on the humanitarian crisis and the severe travel risks.

- U.S. Department of State – Yemen Travel Advisory: Provides the highest level of warning, advising citizens not to travel.

- UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office – Yemen Travel Advice: Advises against all travel to Yemen and provides detailed security information.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – Yemen: The most reliable source for information on the ongoing humanitarian crisis, needs, and response.

- Doctors Without Borders (MSF) – Yemen: Offers on-the-ground reports and information about the healthcare crisis from one of the few international NGOs operating in the country.

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Yemen: Provides information on their activities related to conflict, detainees, and restoring family links.

Leave a Reply